Designing Innovative Sustainable Neighborhoods

Avi Friedman

- 238 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

Designing Innovative Sustainable Neighborhoods

Avi Friedman

Información del libro

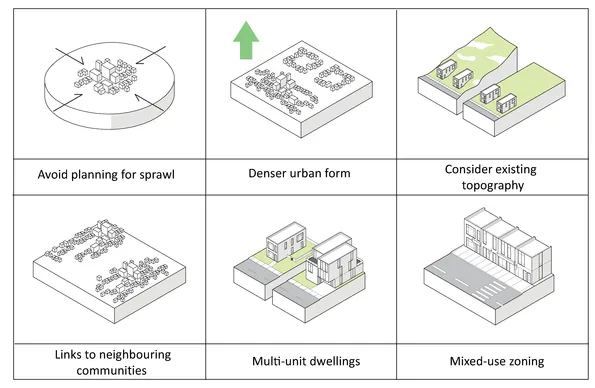

This book covers fundamental aspects of neighborhood planning and architecture along sustainable principles. Written by a designer and instructor, the book's fully illustrated chapters provide detailed insights into contemporary strategies that architects, planners and builders are integrating into their thought processes and residential design practices.

Past approaches to planning and design modes of dwellings and neighborhoods can no longer sustain new demands and require innovative thinking. This book explores new outlooks on neighborhood design, which are propelled by fundamental changes that touch upon environmental, economic and social aspects. It presents contemporary well-designed and illustrated examples of communities and detailed analysis of topics including the depletion of non-renewable natural resources, elevated levels of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. It also explores the increasing costs of material, labor, land and infrastructure, which pose economic challenges; as well as social challenges including the need for walkable communities and the increase in live-work environments.

The need to think innovatively about neighborhoods is at the core of this book, which will be useful to students and practitioners of urban design, urban planning, geography and urban systems; and to architecture studios focused on sustainable residential development.

Preguntas frecuentes

Información

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Designing Sustainable Environments

1.1 The Origin of Sustainable Thinking

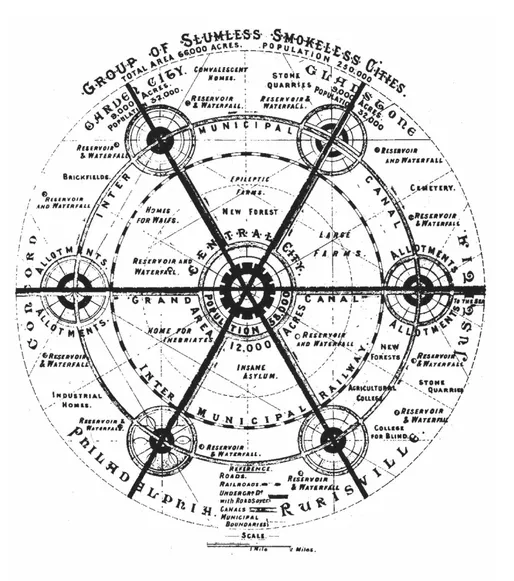

1.1.1 The Genesis and Evolution of Suburban Planning

1.1.2 The Genesis of the Contemporary Sustainable Framework