eBook - ePub

Industrial Policy in Europe after 1945

Wealth, Power and Economic Development in the Cold War

C. Grabas, A. Nützenadel, C. Grabas, A. Nützenadel

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Industrial Policy in Europe after 1945

Wealth, Power and Economic Development in the Cold War

C. Grabas, A. Nützenadel, C. Grabas, A. Nützenadel

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Bringing together renowned scholars in the field with younger researchers, this interdisciplinary study of the history of post-war industrial policy in Europe investigates transfers across borders and locates industrial policy in the context of the Cold War from a global perspective.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Industrial Policy in Europe after 1945 un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Industrial Policy in Europe after 1945 de C. Grabas, A. Nützenadel, C. Grabas, A. Nützenadel en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Geschichte y Weltgeschichte. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

GeschichteCategoría

WeltgeschichtePart I

Western Europe

1

European industrial policies in the post-war boom: ‘Planning the economic miracle’

James Foreman-Peck

Cardiff University

1.1 European industrial policies in the post-war boom: Planning the economic miracle

The ‘Thirty Glorious Years’ of 1945–75 saw unprecedented European prosperity on the back of unique economic growth. Was it the result of good luck, fortuitously benign international relations or carefully planned policies? ‘Planning’ was fashionable for much of the period and is definitely not now. What exactly is or was this ‘planning’? Was it simply intellectual fashion, or was planning a major contribution to the boom, a key component of industrial policy? Industrial policy covers a broad range of policies and there are different understandings of what the term means. So first some definitions are set out – before a broad conception is chosen. Then the pattern of European industrial production at the beginning of the period is described, together with the enormous scope for ‘catch up’ growth. Germany and Britain dominated European industrial production in 1950, but outside Europe, the United States had been extending its productivity lead for three decades. The opportunities for rapid European economic growth and industrial development lay in absorbing the techniques and organizations behind this lead.

Europe’s pattern of growth and convergence between 1950 and 1975 shows the extent to which these opportunities were exploited. This configuration is a key to the drivers of the post-war boom. Lower-income economies had more opportunity to grow faster if they pursued the right policies – essentially being open to absorb the technologies and ideas that had proved themselves elsewhere. The distribution of countries around the average convergence line distinguishes the more from the less successful. How closely the Western European economies cluster indicates either the principal importance of supranational policies that affect them all, or the successful pursuit of similar policies, or both.

National styles of industrial policy differed more in presentation than in practice – the contrast between France and West Germany is instructive in this respect. Different concerns with defence, along with state support for R&D, also closely related to security in many countries, were a greater source of industrial policy divergence. Thanks to the apparent successes of the Soviet Union in the 1930s, and the perceived superiority of state resource allocation compared to the market, boosted by wartime experiences, planning was in vogue throughout Europe. Planning by direct controls on market participants, such as rationing, gave way to the indicative planning of the 1960s, with new challenges of plan implementation, particularly depending on whether or not state industries were involved. Nowadays, competition policy is the most intellectually popular industrial policy, so an attempt is made in this chapter to assess the actual and potential importance for the post-war boom.

The conclusion is that the most important factor in this remarkable period for Western Europe was not planning, but a general industrial policy, as defined here (though not always accepted as one): the drive for increasing trade and investment openness, largely, but not exclusively, under the heading of ‘European integration’. Behind this striking contrast to the 1920s and the 1930s, lay the United States’ commitment to a non-communist Western Europe and a willingness to tolerate otherwise ideologically unacceptable deviations from their preferred international economic order. On the other side of the Iron Curtain, Soviet perceived defence needs were served by an economically integrated Eastern Europe, with similar, though less successful, convergence and ‘catch up’.

1.2 What is industrial policy?

Here, industrial policy is an analytical concept rather than a historical one (i.e., used by agents at the time). Industrial policy is concerned with an aspect of industry as an objective, and sometimes as an instrument. Nowadays, the central aspect is widely assumed to be productivity or ‘competitiveness’. Traditionally, industrial policy includes ‘catch up’ or industrialization policies. But ‘stability’, especially of employment, is also of great importance, as was ‘security’ through the national ability to supply military high-technology goods – nuclear, aerospace, computers, plus increasingly ‘health and safety’ of industrial products. In addition, wider concerns about the efficacy of market allocations or the competence of business elites may, or should, promote industrial policies in pursuit of ‘equity’ or wider ‘community interests’.1

A common distinction (though in practice a somewhat slippery one) is between ‘vertical’ sector- or firm-specific policies on the one hand and, on the other, ‘horizontal’ general policies. Horizontal policies can be divided into those influencing the legal and institutional framework – competition policy or general trade liberalization, for instance – and those modifying technology and markets for inputs and outputs – investment subsidies, education loans and grants, even sales taxes.

Vertical policies are structural. They are intended to alter the relative importance of industries and firms (some definitions of industrial policy are restricted to vertical policies).2 Health and safety legislation and procurement policies generally have obvious structural effects even when nominally they are horizontal policies. Supporting ‘national champions’ or ‘picking winners’, a feature of French industrial policy is a vertical policy,3 as is ‘helping losers’, such as Rolls Royce in 1971, or VW at the end of 1974.4

Instruments of industrial policy traditionally have included tariffs and trade controls, which are worth noting because of the extraordinary reversal in their use over the period of interest – especially with the formation of the European Steel and Coal Community (ECSC) and the Common Market, but also with the Kennedy Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). State ownership of industry – required to pursue the ‘public interest’ and break even – was a popular institution of the mixed economy and pervasive in Eastern Europe. Italy’s Mezzogiorno policy was to be implemented by these organizations, as was much of French ‘planning’. ‘Guidance’ or information provided by indicative planning became popular in the early 1960s after the direct allocation, rationing and physical controls of the later 1940s and early 1950s. Other instruments were tax incentives for R&D, for savings or investment, and low-interest loans. Subsidies for, or direct supply of, education and training increased skills and lowered their ‘price’ (if effective). In both the cases of capital and labour market policies, reducing the input price to industry was intended to increase output (they also unintentionally encouraged factor substitution). To reduce output, discriminatory taxes on goods with negative externalities (‘sin taxes’ on cigarettes, alcohol and perhaps even petrol) might be imposed. Controls on the price of other inputs, such as energy and water, were supposed to support industry at the expense of utility companies, of taxpayers or of private consumers, or to subsidize consumers or voters by burdening industry. Legal remedies for the exercise of monopoly power – discouraging or forcing abandonment of restrictive practices (the UK’s 1956 legislation) and prohibiting mergers – were not especially popular policy instruments in this period.

Explaining why particular industrial policies were pursued can require different concepts from those necessary to understand which policies should have been followed. The 30 or 40 years after the Second World War marked the high tide of belief in effectiveness of state intervention. Supposed failures of the market in 1930s, the apparent success of the Soviet system and state hubris – reinforced by the ability to ensure failures were ‘official secrets’ in war or emergencies – explain some part of this popularity of state initiatives. Economic crises and slumps – threats to order from concentrated mass unemployment – were always reasons why states have bailed out, nationalized or reorganized major employers or important defence contractors, in attempts to prevent their closure. European integration and the associated industrial policies undoubtedly owed something to the Cold War and US policy, as the contrast with the inter-war years makes clear. Another driver of industrial policy was when one state learned, or at least copied, from others deemed to have been more successful. Spain duplicated Italy’s state holding company and Britain attempted to imitate French indicative planning with the National Economic Development Council.

Government’s greater share in national income provided industry lobbies and trade unions – rational self-interested agents – with more scope for their activities. ‘Regulatory capture’ was a payoff to firms when government departments or agencies regulated in the interest of firms rather than, as they should, in the interests of users of firms’ outputs. National security (supported by industry lobbies) provides a reason for the magnitude of British and French spending on the nuclear and aerospace industries (as well as a justification).

1.3 Initial conditions

By the end of 1947, Europe’s working population and productive capital had returned to pre-war levels, though it was differently distributed.5 The UN Relief and Rehabilitation Agency ceased work at that point, but in June, the US Secretary of State announced the Marshall Plan (European Recovery Program). Despite the onset of the Cold War with the Soviet Union’s Berlin Blockade in 1948, the plan maintained the impetus of Western European recovery. The same year as the Berlin Blockade, the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) was created to manage Marshall Aid. In turn the OEEC established the European Payments Union (EPU) in 1950. Europe’s external position was less favourable than before the war; international trade and investment were dislocated. Hence, the contribution of the EPU, replacing bilateral trade with multilateral trade (that nonetheless discriminated against the dollar), was vital. While the EPU was gradually unlocking trade, there were bottlenecks, power cuts, and shortages. Direct controls, rationing, quotas and administered prices were both policy responses and contributors to these problems.

German recovery was sufficient that by 1950, had Germany been united it would have been the largest industrial producer in Europe (excluding the USSR from Europe). As it was, the UK, with about one-quarter of total industrial production, was the biggest, while France produced less than one-half of the UK’s industrial output. Italy and East Germany were the only other intermediate-size industrial powers. West Berlin’s industrial production alone was greater than the combined total for Greece, Hungary and Ireland.

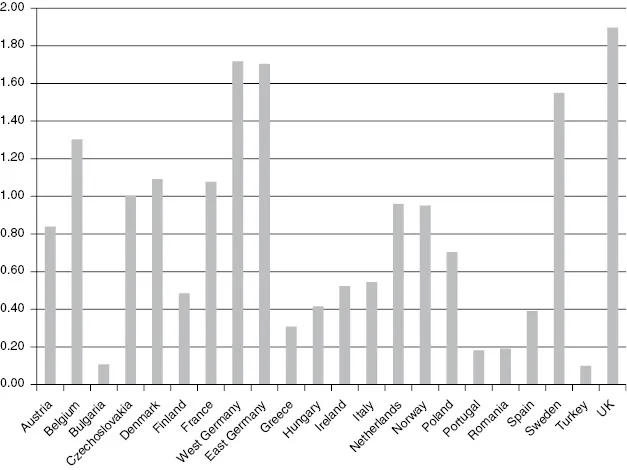

Dividing the distribution of industrial production by national population yields an index of relative industrial development (Figure 1.1). Sweden was close behind the two Germanies, followed by Belgium. France was on a par with Denmark.

Figure 1.1 Distribution of European industrial production in relation to population, 1950 (1 = average)

Source: Calculated from United Nations (1953); and Maddison (1995), table A3, population estimates.

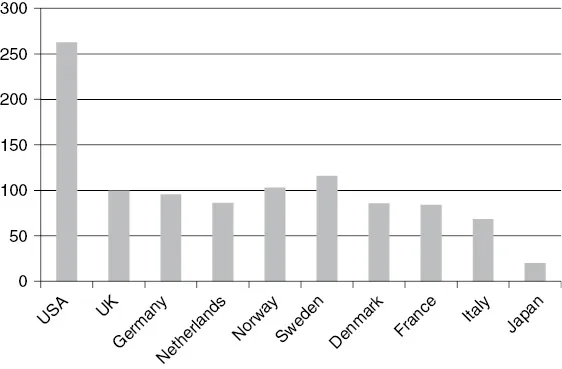

The productivity gap with the US for West Germany and the UK was no less striking than for the rest of Europe. Manufacturing labour productivity was more than 160 per cent greater in the US than in the two largest European industrial economies (Figure 1.2). The gap was even larger in utilities, transport and communication and mineral extraction.6 The scope for catching up was, therefore, enormous.

Figure 1.2 Labour productivity in manufacturing in selected countries, 1950 (UK = 100)

Source: Broadberry (1997), tables 4.3, 4.4, 4.5 and 4.6.

1.4 Integration and convergence

Comparing initial relative industrialization in 1950 with subsequent industrial growth rates suggests a common European proce...