Early on in my study I noticed that some members already had an idea that the TWoP community had the potential to be very powerful in terms of television’s history. “I’m so happy to be part of the TWoP community,” one member wrote, “we may end up making television better whether we want to or not.” What was it that drew so many people to this little corner of the web? Some cynics would argue that negativity is bound to flourish in any new space on the web, but much more than a shared dislike of television programs brought viewers and kept them there. This was no small fan site. Television Without Pity was a very large web community, and its size was directly related to the welcoming culture created by the founding members. A great discussion topic can bring a lot of people to a message board, but a well-designed and managed message board keeps them there. The writers employed by the site to recap episodes were engaging, and the site’s design was easy on the eyes. It was the message boards, however, that brought the real traffic, sometimes millions of page views in a month. The site founders played excellent hosts and understood that to keep the discussion relevant and interesting, attention to rules and forum design was key. Creating and maintaining great conversation took some doing, and was not always successful. A powerful combination of site design, discussion moderation, and community building kept the membership growing from its early incarnation in 1999 until the final message board post in May 2014. However, what drew many in and outside of the Hollywood elite was likely its independence from any particular fandom. In the pages ahead, I discuss the size and nature of the site, how it was able to build a community, and how I, as an ethnographer, went about studying the site. The sheer size and nature of the site was powerfully new, and required rethinking of traditional ethnographic models. How this group of people used the Internet to make meaning from television and create a sense of community is important for understanding the changing nature of the television audience.

The Birth of Television Without Pity

Television Without Pity was a website that went through many incarnations and overhauls. Started by web entrepreneurs Tara Ariano, Sarah Bunting, and David T. Cole (also known as Wing Chun, Sars, and Glark on the boards), it began in 1998 as DawsonsWrap.com and was devoted exclusively to the WB series Dawson’s Creek. Bunting and Ariano (both English literature majors at Princeton and University of Toronto, respectively) had been avid posters on a message board forum all about Beverly Hill, 90210 and when they started to watch Dawson’s Creek, Cole suggested they create a space online to write about the show. As its popularity increased, so did its purview, expanding to the recapping and discussion of other shows, and via a name change became MightyBigTV.com. According to Cole, their first site was more of a labor of love than a business idea, “When we did Dawson’s it was just for fun, and we saw something there. We had so many friends that were good writers and put two and two together.” What later became a huge community of users and a large platform for writers was not on the radar in 1999 when the first site was conceived: “It wasn’t like we were setting out to do it, you didn’t make sites like that back then. Everyone was on Geocities, doing home pages,” said Cole. The trio started conceiving the site as a kind of television program, “kind of like a Daily Show for television, before Talk Soup was created.” They went to Los Angeles to pitch the idea. In doing the legwork for a television property, they realized that Coca-Cola owned a trademark for “Big TV.” Fearing the legal ramifications of moving forward with a similar name, the site underwent a name change to its final moniker, Television Without Pity in 1999, or “TWoP” in the acronym-loving parlance of the Internet.1

Their mission, according to co-founder Sarah Bunting, was to hold networks and writers accountable by analyzing their work and “not just passively sitting around and watching.”

2 The impetus for the site and its community is criticism, as is evidenced by the site motto, which boldly declared, “Spare the Rod, Spoil the Networks.” Its history is a rocky one, with various attempts to keep the site afloat and pay their writers. Initial attempts to secure advertising on the site were not successful, according to Cole, even after joining with Yahoo’s advertising arm in 2002:

First, we wanted to cover costs, and at the start, we did. And when everything crashed in the early aughts, we stumbled hand-to-mouth for like six or seven years. And then, one weird month we got calls from all these places. We never tried to sell the site. I don’t know whether there was an industry report going around, saying “TV sites are going to be the new hot thing.” Jump the Shark and Buddyhead got bought at the same time. We had five places in the span of a month offering us money. And we were excited because we had hoped that by selling we could do bigger and better things, like video content, a version of the TV show we pitched.3

That year was 2006, and by 2007, the site underwent an overhaul when its founders finally sold the site. It was transferred into the hands of Bravo, a television channel owned by network giant NBCUniversal. A year into the Bravo ownership, the founders of the site quit. Five years later, in 2013, Bravo announced that it was shutting down operations and no longer hosting the message boards. Visitors can no longer read the dynamic conversations that took place there.

When I first joined the site as a member in 2000, it was actively recapping about 35 different television programs, and had message boards for each one. At the height of the study in 2007, the site employed many more writers and there were about 55 programs recapped on a regular basis. Because users could create their own topics (within a few basic parameters), the message boards grew. There were message boards for programs that had been cancelled as well as programs the site did not officially recap, such as sitcoms and cartoons. It grew to become one of the top five most popular television websites on the Internet, eventually generating over 70 million page views a month. The founders claimed to have over 1.5 million unique viewers when they sold to Bravo.

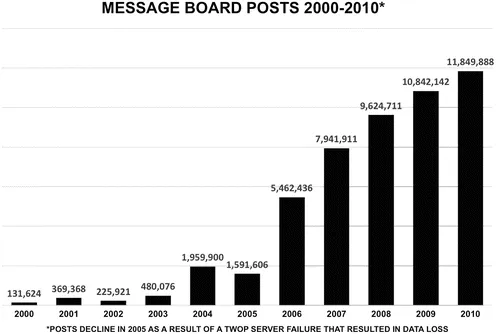

4 By the time I had completed my survey of the site in 2010, it boasted 1,849,888 individual posts in the message boards (see Fig.

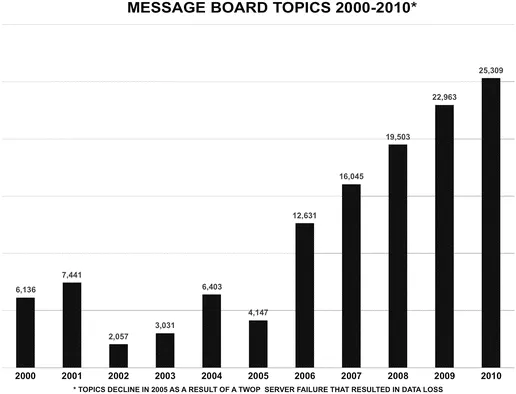

1.1). There were 25,309 topics on the site and both of those numbers were a result of a steady climb over the course of the study. In my interview with site founder David T. Cole, he recalled that there were over 200,000 members registered to use the message boards when they sold the site in 2007.

Users had designated titles based on how many times they posted in the message boards. Table

1.1 indicates that user hierarchy.

Table 1.1User designations

0–9 posts | Just tuned in |

10–99 posts | Channel surfer |

100–199 posts | Loyal viewer |

200–349 posts | Video archivist |

350–999 posts | Couch potato |

1000–4999 | Fanatic |

5000+ | Stalker |

In addition to these monikers, there were designations for site staff (Network Executives) and moderators (TWoP Moderators), as well as the site administrators (Head of Programming). Over 100,000 members of the site qualified as “fanatics” or members with over 1000 posts to their usernames. Most posters in the forums I studied during my project were coded as “Fanatics,” and all interviewees had made at least 100 posts. There were also many “Just Tuned In” members, who began to post at the start of each new season. The designations were a way of creating a hierarchy so that when new members join a discussion, they were shepherded into the norms of the boards by more experienced members. The designations did not, however, indicate how long a person had been a member. For instance, one of my survey respondents listed as “Just Tuned In” indicated that they had been “lurking” (viewing discussion, but never entering it) for years. Just because they had not logged as many posts did not mean they did not know the intricacies of the site or the boards.

The number of users grew alongside the number of topics. During the study, 158 television programs comprised the major topics of discussion between 2000 and 2010, each program having subtopics. Some of the more popular programs, such as

Lost, had more than 400 topics alone (see Fig.

1.2). There were also hundreds of general topics for discussion such as commercials, gender, race, and censorship.

By the time the site had left behind the name Mighty Big TV and emerged as Television Without Pity, it was vast in terms of both number of users and breadth of topics. A clear and simple design strategy made the site easy to navigate and understand, even for the newest users.

Key Aspects of the Site’s Design

The social hierarchy, as well as the look and feel of the message boards, was about simplicity and clarity. The site kept members coming back by creating an atmosphere of “easy conversation,” though a labyrinth of rules and careful design lay beneath the simple flow seen on the surface. The message boards were well organized and easy to read, even though the most popular boards sometimes logged thousands of posts each day. The topics were categorized and color-coded. Each forum in the message boards had topics that ranged from very specific to very general. Some were for one episode only, while others were devoted to discussing the story arcs of an entire season.

Message board posts were formatted in a consistent, simple pattern. The format was stripped of the pictures, avatars, favorite quotes and signatures that were common on many other online message boards. The lack of these personal accessories created what appeared to be an uninterrupted flow of discussion, something the founders seemed to prize. When I asked founder David T. Cole about his design strategy, he said that he used Invision Power software to create the boards, but he modified it considerably: “I went in and rebuilt it, made it a lot cleaner, easier to navigate.” His goal was to strip it of things he felt were cluttering up the landscape in order to focus on ease of use and to service the conversation. Cole said, “whatever we did design-wise was just to highlight the content. That usually makes things easier to navigate.”

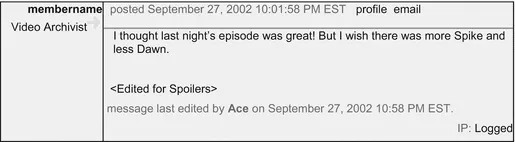

5 His approach was to focus on user experience, and guided design with that in mind. Figure

1.3 provides an example of the format of a message board post at

TWoP.

The user’s profile and email address were available to the right of the member name (if she or he had elected to make that information public). From this post, a reader could tell that this member had logged in at least 200 posts in his or her time as a member from the “Video Archivist” title. Without elements like signatures and emoticons or other images, it allowed the message boards to mimic real world conversation better. The flow of discussion went from one post to the next with minimal disruption, and even quoting a previous post did not detract from the overall calm tone of the design.

The Moderator’s Heavy Hand

Moderators vigilantly monitored the message boards, enforcing rules of polite conversation. Instructional guides (FAQ’s, “Frequently Asked Questions”) instructed posters to refrain from stating their opinions as fact, encouraged them to read the boards thoroughly before posting new comments, asked that they try to use proper grammar and spelling, keep arguments polite, and stay on topic. If a poster derailed discussion or became overly confrontational, they were given several warnings and eventually banned from posting on the site.

The policies for the Television Without Pity message boards were complicated, and each message board has its own set of FAQs. While these policies were intended to keep the site running smoothly and keep conversation polite, they were also likely holdovers from the early days of the site, when bandwidth conservation was paramount. The conversations in the message boards were thus not completely free flowing, but rather adhered to a hierarchical system that required the moderators to determine relevant discourse. Going off topic, being impolite, ignoring proper spelling and grammar were all discouraged on the site’s message boards.

The FAQ’s for both ...