The environment we live in these days is very different from that which our ancestors 10,000 years ago had to cope with. In those days you had to decide in a split-second whether the shadow behind the bush was your lunch, or whether you were more likely to be its lunch. We must have been quite good at those split-second decisions

, because we have survived as a human species. We learned to react before we think. The problem is that we still have the same hard-wired reactions; our genetic make-up has not changed significantly since that period. Unless we become aware of the limitations imposed on us by our evolutionary heritage

, we will continue to act before we think and run the risk of behaving like latter-day cavemen.

The influence of our

evolutionary heritage

is such that even modern humanity, when it has to face the basic

dilemmas of life

, tends to select the first of each pair of options below:

short term doing rather than long term thinking

simplistic scope rather than a comprehensive scope that requires reflection

take refuge in fantasy rather than face a difficult reality

Systems thinking

is a powerful tool for addressing these dilemmas. The archetypes

developed offer us sharp insights into the way we unintentionally create patterns that keep bringing us back to the problems we trying to solve.

Despite our most well-meaning intentions, we often mess things up. Our patterns frequently arise from failing to take a longer-term view

and thereby unconsciously limiting our own growth, or adopting the wrong solution and continuing to use it. Other such patterns arise from looking at issues too narrowly, or by spending so much time battling against symptoms or competitors that we never address the root cause of our problems. Still others take refuge in fantasy and deny the changes taking place around them in reality. To make wise decisions

you must look beyond the beautiful flowers on the surface of the lily pond; you must investigate what has caused the situation to develop in this way, by looking under the water surface at the root system and the water that surrounds it.

If you don’t know where you are heading, all actions can seem equally valid. Without a purpose, all definitions of intelligence are meaningless. For organisations to prosper they must know where they are going. They must identify the key to their success and the engine of their growth. They must know how they create added value now and in the future, and what they want to contribute to the environment in the years ahead. The Value Creation Model

is an excellent way of visualising this essential ingredient for survival

as an organisation. Organisations do not exist in a vacuum—they must be aligned with the business environment.

An organisation needs a vision

of what it is now, what it wants to be in the future and how it will continue to create added value for the environment so that it be able to survive. And once you know where you want to go, you have to implement the resulting strategy by involving the work floor.

To address the daily problems in the cooperation

patterns we create, we present a well-established six step protocol: from incidents, via trends, scoping, mapping patterns, and driving forces

to proposals for interventions.

Although these steps sound anodyne enough, recording incidents and analysing trends is in itself a major challenge. These steps are about analysing the current state of things, which often involves a challenging confrontation with actual reality rather than the reality we would like to see.

Before you can even think about planning interventions, you must identify the forces that drive people’s behaviour. We like to believe that we behave rationally, but in most cases this is a misconception. Because emotionally-driven behaviour is the norm, it is crucial to understand which emotional drivers are dominant in a given situation. The polished person you think you see—even the one in the mirror—is just a caveman in a suit or a cavewoman in a dress.

The nuts and bolts of the presentation of systems thinking

are outlined in the annexe.

The last chapters summarise the content in practical form in order to achieve a balance of thinking and doing—a basic ingredient for dealing wisely with our organisations and enabling them to prosper.

A problem arises that’s costing your company a lot of money. Every day that the problem persists, the losses mount up. What do you do: do you quickly find a solution, or take the time to identify the cause of the problem? Systems thinking helps us deal wisely with dilemmas like this.

Systems thinking is all about realising that there are moments when you have to postpone the doing and think. It’s about those situations that require a shift from learning to improve on what you are already doing (single-loop learning), to realising that you have to learn something completely different (double-loop learning).

It’s a way of introducing insight into the complexity of organisations, or in a broader sense: of social systems. Social systems are defined mainly by fixed patterns of which we are often simply unaware. We’re so used to them, so bound up with them, that we can’t even see what’s happening right before our eyes, like the proverbial fish that doesn’t know what water is.

This is often why organisations can be taken completely by surprise by events that outsiders have often seen coming for a long time. For the organisation concerned, it seems that business has imploded all of a sudden, whereas in fact the process has been going on for quite a while.

And you build these patterns together with your environment. If everybody around you sees the departure of customers as a normal part of business, it becomes part of your frame of reference , and you are unaware of it. One customer goes away, and then another and another, and suddenly the bottom falls out of the business. People within the organisation have failed to see the pattern, because they see each event as a separate incident: “Who cares? It’s just one customer…”

Systems thinking is a tool to help you identify patterns like these, so that the organisation can face the assumptions they have about their environment and begin to tackle them.

Looking at the Whole Picture

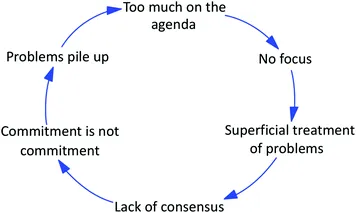

A very simple example of systems thinking is the analysis of how people manage workload. It happens in all organisations: the workload suddenly goes up. A short while ago you could comfortably manage your work, but suddenly it spills over your desk and it’s getting worse. You don’t have the time to properly finish your tasks and you cannot meet deadlines, just like everyone else, who is also overloaded. The problem is often discussed within the group, in a bid to find a way out, and usually it ends with a solemn promise to stick to agreements and deadlines. Agreements are identified as the action point, because that’s the most visible part of the problem. Wherever you see notice boards in conference rooms with: agreed = agreed, you can be sure that the reverse is true ….

In

systems thinking you factor in the overall context and the situation looks more like Fig.

2.1. The various phenomena are all probably related in one causal relationship. If we’re aware of the relationships, we can think about more nuanced

solutions and increase the opportunities for interventions. Insight into the relationships between phenomena enables us to intervene more effectively. In this case it’s probably smart to agree on the priorities and stick to the priorities that have been agreed upon. It’s an example of changing from working harder the way you used to, to working differently.

Unintended Side Effects

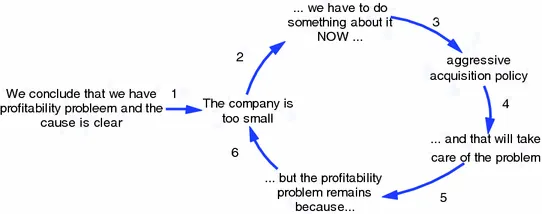

In the foreword we cited Imtech as an example of a company that lurched from one problem to the next. In fact Imtech used quick fixes all the time: they acquired 80 companies in 10 years! The quick fixes of acquiring another company had the opposite effect of what was planned; instead of growing stronger, they pushed the company to the brink of failure. Imtech made the problems worse by deploying the sort of faulty reasoning to which we are all prone: this is a problem; we have to deal with it now. They were probably thinking unconsciously in terms of steps 1–6 in Fig.

2.2.

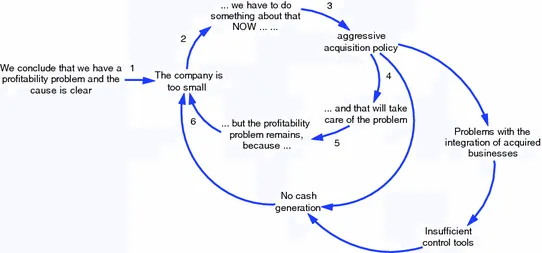

But they did not foresee that

acquisitions could have all sorts of

unintended side effects in the longer term, as shown in Fig.

2.3.

Like many other organisations that fail to think systemically, Imtech went bankrupt. Once again this example highlights the need for a change in thinking rather than...