![]()

Chapter 1

Shipped out to Germany

Thousands of times, I have been asked, “What made you go back to Germany?” Thousands of times, I have replied, “I didn't go back; I was born in Canada and had never been to Germany.”

In March, 1939, two months before my fourteenth birthday, I was yanked out of Suddaby Public School on Frederick Street in Kitchener, Ontario, and, together with my brother Oscar, who was 1½ years younger than I, and three other youngsters from Kitchener, was put on a train to New York There, the five of us boarded the express steamer Europa for the voyage to Bremerhaven in Germany.

Making travel preparations in Kitchener for Oscar and I had not amounted to much more than hurriedly and quietly getting together our Canadian passports and our free tickets. That brief spell had elapsed without our being given any reason for our having to leave Canada or, for that matter, for our having to maintain silence regarding our impending departure. Often I have wanted to fathom why, surrounded by secrecy, Oscar and I were shipped out to Germany almost 70 years ago.

My father, a stationary engineer at Forsyth's shirt factory in Kitchener at the time, would read well-circulated copies of various German illustrated periodicals. That I knew. He would, I also knew, drop in after work at Colarco's fruit and vegetable store, near the city hall in Kitchener, and, I suppose, have a chat with Signor Colarco about Axis developments.

Yes, my father was pro-German, but I have to look far beyond Colarco's counter to explain, if I can, what it was that made him and my mother decide to send Oscar and me to Germany.

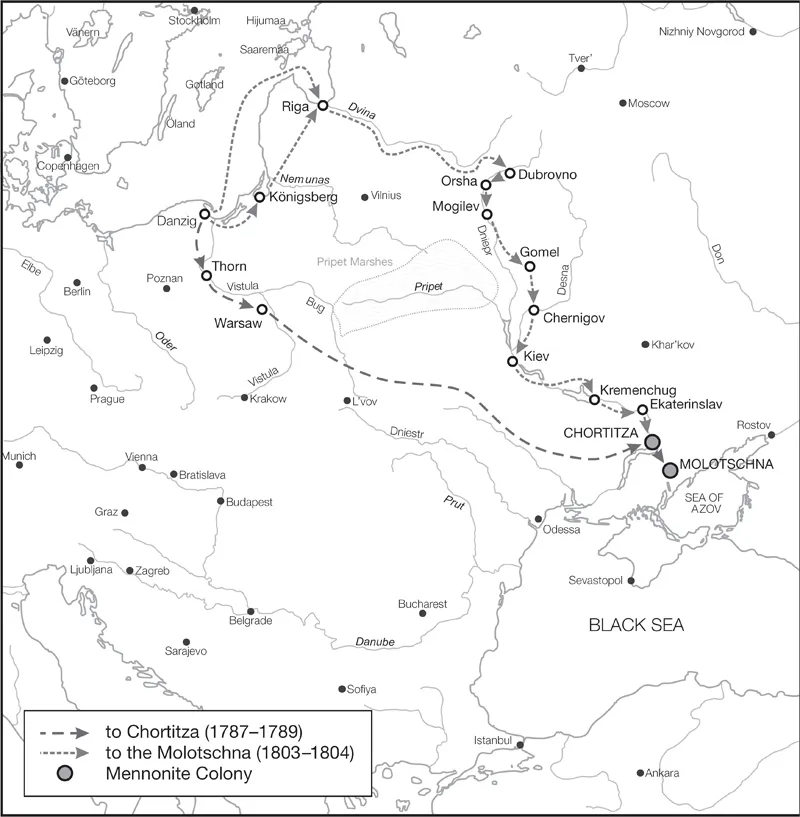

Having arrived in Canada from the Ukraine in 1924, my parents – please consult the relevant maps for the location of the district in the Ukraine from which they hailed – after working for almost a year on a Pennsylvania-Dutch Mennonite farm near Waterloo, Ontario, moved to the Portage la Prairie district of Manitoba. The Canadian Pacific Railway had advanced many Mennonite immigrants the money for their fares to Canada under the condition that they settle on lands adjacent to CPR tracks.

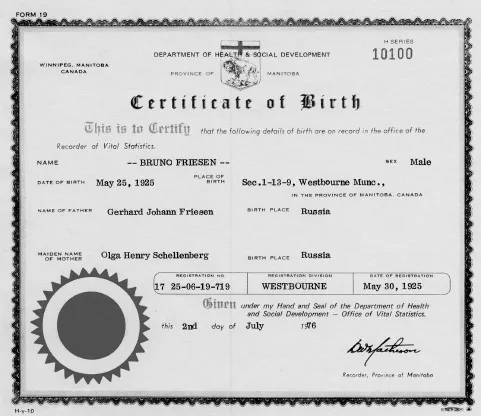

I was born on Section 1–13–9 in Westbourne municipality on May 25, 1925, and was just old enough to start school in Waterloo after my parents had abandoned their land at Westbourne and returned to Ontario. In Manitoba, they had tried in vain to farm 160 acres, part of an agriculturally inferior tract bought by ten families while it lay under snow. Annually, widespread spring flooding prevented the timely seeding of practically all of that expanse.

Among all Mennonites burdened by it, the CPR loan was referred to as our travel debt, and for them that debt remained, for years, a financial millstone.

The Great Depression of course was the primary cause of so much misery. It robbed my father of any hope that he might emerge debt-free in Canada.

My parents had never been to Germany. Neither had my grand-, great-grand-, or great-great-grandparents. However, because of their first language–German–all of them had maintained strong cultural and economic ties with Germany. The German-speaking population of the Mennonite colonies in the Ukraine had for decades mail-ordered their agricultural machinery, their reading material and, starting in the early 1900s, even their automobiles from Germany. In “Soviet Armour Ambushed at the Lake at Lessen in West Prussia,” one of my following stories, I refer in detail to some of my forebears' strong traditional German ties.

Before we moved to Kitchener in 1937, we lived at 132 King Street South in Waterloo. Every Saturday evening, a coterie of Mennonites, including my parents, would congregate at 132. A polyglot bunch they constituted, speaking High German, Low German, Russian, Ukrainian–and some English. High German is the official language in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Low German or Plattdeutsch–platt is German for flat–is the informal German spoken in flat, or lowland, northern Germany.

Map 1 Mennonite Migration from the Vistula to Southern Russia

Every letter from relatives or friends in the Old Country that did get through to the group in those hard times was neatly written in High German, no matter how low-grade the stationery, as was every letter of response.

On Saturday mornings, the W-K, or Waterloo-Kitchener, United Mennonite Church on George Street in Waterloo conducted its one-room German school in the church basement. I acknowledge that during my early months in Germany I made good use of most of the rather rudimentary German I had learned at W-K; however, it turned out that the unworldliness of the school's one level of text book, strengthened by the school's one instructor, a strait-laced lady from a fine Russian Mennonite family, had left me incapable of enquiring, in refined German, where the next toilet was.

In 1985, about 50 years after I last attended German classes at W-K, the surviving members of the family of a former custodian of the German school's text books presented me with the book I had used on at least one Saturday morning so very long ago. It was mine all right, so to speak, for it bears my full name and what was then our address scribbled boyishly onto the inside of its back cover.

This old book, in itself, attests to the Russian Mennonites' faithfulness to the German language. Its full title is Deutsches Lesebuch für Volksschulen in Russland (German Reader for Primary Schools in Russia). Published in 1919 by Gottlieb Schaab in Prischib, a town adjacent to the north-western corner of the Molotschna, one of the oldest Mennonite colonies in the Ukraine, it is one of a dozen or so identical copies that were used for years at W-K, and would have been brought to Canada from Russia, probably in the early 1920s, by persons to whom the German language meant a great deal.

In my own modest library, there reposes, next to the reader I have just referred to, a book entitled Poems of Nicolaus Lenau. It has an embossed spine and covers, and was published in 1877 in Stuttgart in Germany. My annotation on the inside of the front cover reads as follows: “Received as a gift from Father at the main railway station in Wilhelmshaven before I left for Canada.” This book, one of a large trunkful that my father had taken with him from the Ukraine to Canada, and from Canada to Germany, signified his love of literature. I am certain that he cherished this particular book more than many of his others.

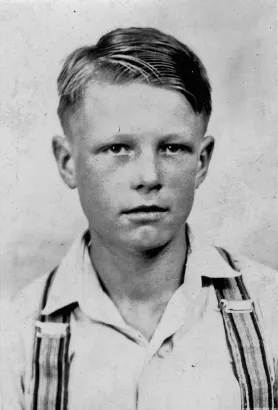

Author at 13 years old - At the age of 13 years 10 months, shortly before Oscar and I were sent from Canada to Germany in March of 1939.

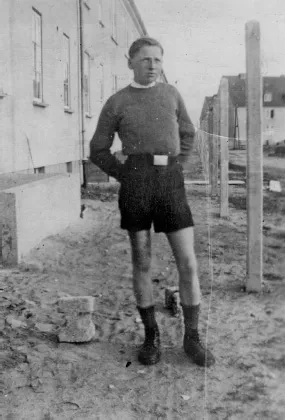

Oscar Friesen - Oscar Friesen at 17 years old, who would be later killed at Houffalize in Belgium in 1944.

Nicolaus Lenau is the pen name of Niembsch Edler von Strehlenau (1802–50). A resident of Hungary, Lenau chose his subject matter largely from outside of Germany. It is not surprising that my father displayed a great affinity for Lenau's work.

Throughout most of his adult life, my father wrote many poems and much prose, all under the pseudonym Fritz Senn. I have a 311-page book, published in Winnipeg in 1987 after his death and entitled Fritz Senn: Collected Poems and Prose. Much of his writing reveals his intense nostalgia for his beloved Mennonite world in the Ukraine.

My mother often related that, as a single young man in the Ukraine, our paterfamilias had spent much time with his books. He was, she emphasized, the youngest of nine children in a well-to-do family, and he hadn't been expected to work hard. That, she said, had left him with a lot of time for literary studies.

Probably contributing to my father's pro-German stance was the fact that, starting in 1917, he was, for a few years, a member of the Mennonite Self-Defence Organization, a paramilitary cavalry established to protect the affluent Mennonite colonies in the Ukraine from the infamous Machno's bandits. This defence organization was trained briefly by German officers and non-commissioned officers. Many purely pacifistic Mennonites condemned those of their brethren who fought the anarchistic forces.

By early 1939, my father's ideas concerning emigration from Canada to Germany had become solidified, largely because of the influence of the Confederation of Germans [Abroad], a Third Reich-backed, propagandistic organization operating in league with many of the German social clubs in North America.

At the time, the Concordia Club, the Kitchener area's largest German club, had its premises above one of the two movie theatres–either the Capitol or the Lyric–on King Street West in Kitchener. On Saturday evenings, the parents, both nominal Mennonites, of the three boys who accompanied Oscar and me to Germany would parade most, if not all, of their ten kids close to the dance floor at the Concordia Club.

Although my parents never frequented the Concordia, our family did, in the summer of 1938, attend the club's annual picnic on cow dung-dotted Kaufman's Flats, beside the Grand River, just upstream from Kitchener. At that picnic, my father was happy to earn a few dollars extra by washing beer glasses in the vicinity of the bar in the beer tent. The occasional glass of suds which one of the busy, perspiring bartenders handed to him in the heat under the canvas must have constituted his bonus.

Probably the Confederation was instrumental in having the train and steamship tickets for Oscar and I paid for from within Germany. In return, the recruiters involved undoubtedly hoped that they had planted boundless love for the Third Reich in the members of our family.

I believe that Fritz Senn or, if you prefer, Gerhard Johann Friesen, could not see himself as a farmer or factory worker in Canada. Germany beckoned mightily, so he sent, as the initial step in his unpublicized plan to transplant his entire family to that promised land, his first- and his second-born there, albeit at a very inopportune time. My mother simply consented. Oscar and I left Kitchener for New York on March 20, 1939, and sailed from there on March 22.

At any rate, we five seemingly outcast boys discovered, in one of the lounges aboard the Europa, a phonograph surmounting a boy-high cabinet of polished, reddish-brown wood, filled with records. Daily throughout the crossing, we had our fun making the thing play for hours at a time. I stress our having so much fun with the phonograph because for us things became absolutely mirthless upon our arrival in Bremerhaven, about one week after we left New York.

My souvenir log of that Atlantic crossing by the Europa shows that she left New York on March 22, 1939, and that she passed Cherbourg, France, and breakwater on March 27, having covered 3,128 nautical miles in 4 days, 22 hours, and 6 minutes. For the Europa to get from Cherbourg to Bremerhaven–the souvenir log also shows that she had to travel another 535 nautical miles to get there–must have prolonged our trip by about two days, making it seven days.

At this point, I had best introduce into my narrative two entire newspaper articles as well as excerpts from another two. Published in the Kitchener Daily Record between March 16 and 24, 1939, the four articles are preserved on microfilm at the archives of The Record in Kitchener, Ontario. Please see Appendix A for the copies of three of the articles.

The subject microfilm reveals its age; nevertheless, the copies made of it on my behalf by Gerhard and Kathie Friesen reflects the concerns about Nazi activity in Canada around the time of Oscar's departure and mine. Note that the Kitchener Daily Record published our names on Friday, March 24, 1939 two days after the Europa had sailed from New York.

Jews Boycott K-W Product Action Said Result of Nazi Activity throughout District

Attorney-General Conant's reported investigation into alleged Nazi activity in the Twin City and district was not in ev...