![]()

William Cobbett (1763–1835) began his working life as a ploughboy in Surrey, born into relatively humble circumstances as the son of a yeoman farmer and innkeeper. A restless youth who craved adventure and the expanse of wider horizons, he eventually enlisted in the West Norfolk 54th Foot and was stationed in New Brunswick in the years immediately following the American war of independence, rising to the rank of sergeant major. Cobbett served in the army for nearly eight years, during which time he became aware of the corruption of the officer class who were defrauding his fellow subalterns. Determined to whistle-blow, he secured his discharge and began proceedings against his superiors in 1792, until he was forced to abandon the suit when he realised that the army and government were closing ranks against him. And so he fled with his wife, Nancy, to France, before emigrating to the United States, where he would remain until 1800. Shortly after his arrival at Philadelphia, Cobbett set up in a trade in which he would spend the rest of his life: a journalist with side interests in printing, publishing and bookselling, including a growing and ultimately voluminous catalogue of works from his own pen. By the time he died in 1835, having spent his twilight years combining his journalism with a career that had eluded him until 1832 – as an MP – Cobbett had authored some twenty million words. The bulk of this oeuvre was published in his long-running and hugely popular periodical the Political Register.

Cobbett was the most widely read journalist of his day – ‘a kind of fourth estate in the politics of the country’, in William Hazlitt’s famous description. An anti-Jacobin turned radical, Cobbett was infamous for his invective and brutal sparring with a growing cast of villains who were held responsible for impoverishing the people, about whom he cared deeply. Unsurprisingly, he was seen by friend and foe alike as an instinctive and sometimes brutish creature of his passions.1 Unsuspecting historians have also followed this assessment.2 The caricatured image of Cobbett as an unthinking writer wielding uncontrolled invective has been punctured by Leonora Nattrass’s literary analysis of his writing: ‘the highly-wrought self-consciousness of his writings are always striving for a calculated effect’, with the purpose being to ‘mobilize its reader’s emotions and ideas in certain directions’.3 Cobbett’s skill was in making his writing look instinctive. As Hazlitt astutely observed, Cobbett was strong in ‘bodily perception’, which he juxtaposed against those like Joseph Priestley whose bodies were merely the envelopes of their minds. It was precisely because he thought with his body that Cobbett’s writing appeared so instinctive and immediate: while reason plods, sense perception leaps, a view that Hazlitt derived from Francis Hutcheson.4 Cobbett’s widely attested brutality – even the appreciative Hazlitt wrote of Cobbett’s ‘great mutton-fist’ and his ‘unwieldly bulk’ – has obscured the fact that he could be an intensely sensitive man of feeling, shaped just as much by the age of sensibility and Romanticism as any other writer who came of age in the late eighteenth century.5 James Grande has read Cobbett’s private correspondence as a form of ‘sentimental radicalism’, anchored in his cultural and stylistic indebtedness to Edmund Burke.6 While hugely insightful, Nattrass and Grande have little to say about the nature, purpose and significance of feelings in Cobbett’s published writing, or how exactly he politicised feeling and with what effect – the focus of this chapter. There was much more to Cobbett’s affective politics than sentimentalism and indebtedness to Burke’s insistence that feeling, not reason, should guide human action, though that certainly played a part. This chapter shifts the interpretative emphasis towards asceticism in Cobbett’s radicalism.7

Cobbett’s biographers have understandably struggled to explain the twists and turns in a political career that lasted from the 1790s to the 1830s. Paying attention to the way he deploys the language of feeling underscores the fundamental continuities in his political career. While principles might be exchanged – from loyalism to radicalism – fidelity to one’s feelings was, for him, sacrosanct. Cobbett’s double volte-face – from radical to Tory, Tory to radical – is less dramatic than historians have sometimes argued. He rediscovered his radicalism in response to his many encounters with Old Corruption – the name given to the deleterious effects of the concentration of political power in the hands of a parasitic elite – as part of the general radical revival in the 1800s. In short, Cobbett became radical to further his patriotic feelings.8 Focusing on his affective politics restores some coherence of purpose to his political career. This is about more than simply noting his unique position among radical leaders of being able to give voice to the feelings of rural workers (the focus of Dyck’s study).9 Rather, it is also about recognising that Cobbett was one of the loudest radical voices in the early nineteenth century who denounced the unfeeling callousness of the elite and the emerging ideology of liberal political economy – what he derisively dubbed ‘Scotch feelosofee’, a quip widely quoted by historians but one whose affective significance has gone unnoticed.

This chapter focuses mainly on the first decade of Cobbett’s radicalism, c.1809–20, and for two reasons. First, this was a formative period in which he articulated the affective politics which would endure for the rest of his public life. Second, because key episodes during this period – his trial for seditious libel in 1810, and his election campaign at Coventry in 1820 – have not received the attention they merit. The chapter explores the origins of one of the central goals of Cobbett’s radicalism: positioning himself and subsequently soldiers and labourers as men of feeling as part of his campaign to further their enfranchisement. It takes as its point of departure Hazlitt’s notion that Cobbett was a bodily thinker by showing how he politicised the senses in ways that celebrated, like Paine, ‘the socially levelling implications of the bonds of feeling’.10 But he went further than Paine in asserting that it was the hard-hearted, senseless elite who were unfeeling, not the people. Focusing on the ways in which Cobbett was vilified by his enemies – which, as the first section shows, frequently turned on accusations that he was brutish and suffered from disordered passions and hardened senses – helps to explain the centrality of this goal. By rereading Cobbett’s autobiography, ‘the progress of a ploughboy’, and through a close reading of his seditious libel of 1809 and the resulting trial, the next section explores the ways in which Cobbett challenged the widely held assumption that working-class men lacked refined sensibility. Attention is also paid to the ways in which he developed a radical version of patriotic feeling to challenge political corruption and the desiccated, unfeeling patriotism espoused by the elite in the final stages of the Napoleonic Wars.11 Cobbett had to walk an affective tightrope on behalf of the poor – a man of feeling, but not a creature of his passions. For all his invective and apparent instinctive outrage, Cobbett also preached a version of ascetic radicalism, as the third section argues. His ascetic radicalism was, however, a Georgian incarnation, which had its violent and crude manifestations (at least as far as the subsequent Victorian variant was concerned). Ascetic radicalism for Cobbett was about displaying appropriate feeling in the right contexts. A charge he frequently made against his enemies was that they failed in this, and in failing rendered themselves unfit to govern.

The progress of an unfeeling brute

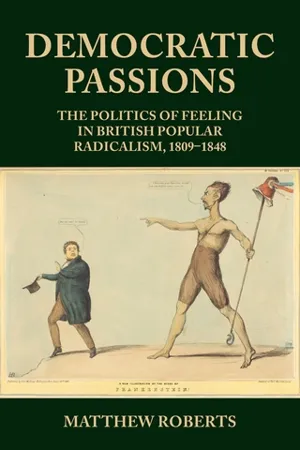

As E.P. Thompson remarked, ‘in tone will be found at least one half of Cobbett’s political meaning’.12 While this tone was central to Cobbett’s affective politics and was the cornerstone of his popularity with the masses, unsurprisingly his invective soon made for a growing list of enemies, some of whom would stop at nothing to put him behind bars and ruin him financially. Cobbett’s enemies tried to turn his tone against him – he was a creature of passion, suffered from disordered passions or, worse still, was an unfeeling brute. Writing in the New Times in 1817, a hostile correspondent cautioned Cobbett that ‘Strong passions are like strong drink! the repeated indulgence of the one is as weakening to the mind, as that of the other is to the body’. But worse than the disordered state of his own passions was the effect that he had on others: ‘no state can be safe or tranquil, where the passions of men are kept in such a perpetual state of fury and agitation, as that which is produced by Cobbett’s seditious publications’.13 Imputations of brutishness were frequently visited on him, both in text and image. In some of the earliest caricatures in which he features, Cobbett is depicted as a bullish, stocky yokel, holding rolled-up copies of his writing which are transformed into club-like weapons, or alternatively with a menacing pitchfork.14 His bodily excess – Cobbett was some six feet tall and widely depicted as portly (no doubt exaggerated in visual satire) – along with the violence he threatened offended the class and gendered norms of polite society.15

Gillray’s satirical Life of William Cobbett, a set of eight prints published in 1809, no doubt with government prodding, was one of the most stinging loyalist attacks on the recent Tory-turned-radical.16 Its effectiveness stemmed not merely from Gillray’s portrait of Cobbett as a traitorous Jacobin, but also from the way in which it equated Jacobinism with disordered passion and brutishness. In the first plate, Cobbett is depicted as a young boy not just tormenting the farmyard animals but appearing almost as one of them, billed as ‘goode entertainment for man and beaste’. In a print from the previous year, Gillray virtually reduced Cobbett to the level of a pig as the leader of the ‘Hampshire Hogs’. Cobbett had recently purchased a house and estate at Botley in Hampshire, which provided satirists with a ready-made lampoon for years to come.17 In Gillray’s latest spoof, we learn that at the tender age of seven Cobbett was already displaying ‘a taste for plunder and oppression’ and that he ‘beat all the little girls of the town’. The imputation of cruelty is further underlined here by the inference that Cobbett has transgressed the gendered norms of chivalric masculinity by beating girls rather than boys.18 The third plate alleg...