![]()

Chapter 1

The Origin of Complexes

The Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) is the collection of social structures, systems, and policies—including institutional racism, the War on Drugs, and mass incarceration—that work together to confine and imprison more than 2 million American citizens. The United States incarcerates more of its citizens than any other “developed” nation in the world.

The PIC is a partnership that was nicknamed the “iron triangle” in the 1996 Report of the National Criminal Justice Commission.3 It is a complicated and sometimes conspiratorial relationship between the government, private industries, lobbyists, and politicians that has been operating since the 1970s. Although reform efforts are starting to gain ground, the effects and consequences of the Prison Industrial Complex will be felt for many generations to come.

History

The U.S. penal system wasn't always this way. From the beginning of the nation's history (setting aside chattel slavery for the moment), and through much of the 18th century, jails in America were used for individuals who were in debt and/or awaiting trial.4 For the most part, crime was deterred through debtor's jail, public lashings, bondage, and capital punishment; the death penalty was doled out for burglary and theft as well as murder. In the early days of the republic, the threat of being banished from the country or of being abandoned in the American wilderness was thought to be effective enough at deterring the nation's crime. Throughout the 18th century as well, jails and punishment were strategically employed to manage criminal behavior. As the nation grew in size, demographics, and scope, however, the challenge of controlling crime became a central feature of public and political discourse. So much so, that political thinkers began to ponder if an open and free society, like the fledgling United States, might in some ways facilitate criminal behavior as opposed to curtailing it.

In the early 19th century, therefore, the notion that criminals could be reformed or rehabilitated took central stage in the American discourse on criminal justice. The nation's first prison systems were the structural results of that discourse—public conversations that wrestled with ways that society might rehabilitate criminals, viewed at the time as citizens who lacked discipline and had lost their way. The reliance on capital punishment and absence of many other alternatives for managing serious criminal behavior in a civil manner created a broad consensus on the need for new methods and new structures for the express purpose of housing and reforming criminals.

The flurry of public debates, pamphlets, and newspaper editorials soon focused on what kind of institution should be the model for America's prison system. The earliest debates revolved around two fairly similar prison systems planned for construction in the 1820s—one in New York according to the “Auburn” model, and the other in Philadelphia based on the “Pennsylvania” model.5 The “Auburn” system versus the “Pennsylvania” system was one of the most intensely debated political and social issues of the 19th-century in America. “If the literature on Auburn versus Pennsylvania never quite matched the outpouring of material on the pros and cons of slavery,” historians Norval Morris and David Rothman have written, “it came remarkably close.”6

Prison Models

The Auburn model, which originated at upstate Auburn State Prison and then at Sing Sing along the Hudson River near New York City, was based on the “congregate” system of incarceration.7 The congregate system, unlike the Pennsylvania system, allowed for some contact between prisoners. Because it did not require the isolation of all prisoners in a given institution, the congregate (Auburn) system was more practical than the Pennsylvania system. It was also more affordable and, for the most part, more manageable for the institution.

For these reasons, the Auburn/congregate system became a pervasive model for prisons across the United States. In the 1820s, Connecticut, Maryland, and Massachusetts built and ran state prisons; Ohio, New Jersey, and Michigan added state prisons of their own in the 1830s; and in the 1840s, Minnesota, Indiana, and Wisconsin also followed suit.8 Nearly all of these facilities employed the Auburn model.

Despite the dominance of congregate incarceration, it raised a number of logistical concerns for the early American carceral state—such as disciplinary techniques, prison garb, and the mobility of prisoners. All of these issues presented systemic challenges to the nation's emerging prison system.9 Although chain gangs and guillotines were certainly cheaper than the huge superstructures that were becoming features of modern American society, the leadership class of the United States believed that the Auburn/congregation system was an altruistic advance in the human project. Prison reformers, by contrast, believed that efforts to construct a system of penitentiaries across the nation not only would address problems inside the institutions but could also solve problems outside the penal system, in the society at large. “With no ironies intended,” write Morris and Rothman, “they talked about the penitentiary as serving as a model for the family and the school.”10

Dawn of the Penitentiary

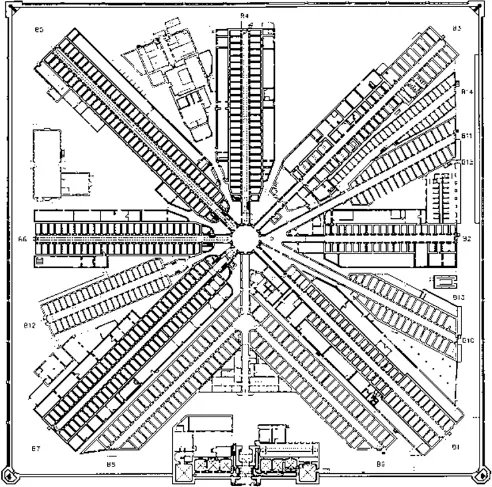

And so, in 1829, Quakers and other reformers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, followed a new and different philosophy in opening the Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP), occupying a full city block in the heart of the city.

Although most criminal justice scholars think of the Prison Industrial Complex as a modern phenomenon, dating to the 1970s, the birth of the penitentiary system sowed seeds of the PIC a century and a half before. The Eastern State Penitentiary was a state-of-the-art facility at the time of its opening. Its proponents asserted the viability of the Pennsylvania system of incarceration even as the Auburn system continued to attract its own political and ideological supporters. Although both systems relied on confinement, silence, and hard labor, the Pennsylvania system was based on solitary confinement as an exclusive form of incarceration and rehabilitation.11 The Auburn system focused on unpaid (i.e., slave) labor by groups of prisoners, but it did allow inmates to come into contact with each other at certain times and locations, such as gathering for meals. But in the Pennsylvanian prison, according to theorist and prison historian Michel Foucault, “the only operations of correction were the conscience and the silent architecture that confronted it.”12

The architects of the world's first institutional prisons believed in solitary confinement as a form of penitence. Isolation, they contended, provided the space and time to reflect and consider God's judgment. Each cell in the ESP thus required prisoners to bow when entering and exiting; each cell was equipped with a small window sometimes referred to as “The Eye of God.”

The Pennsylvania camp saw itself as purist, taking the idea of reform through isolation to its logical conclusion. It separated inmates from each other—to the point of placing hoods over the heads of newcomers so that as they walked to their cells they would not see or be seen by anyone.13

In a contemporary context, with horror stories like that of Kalief Browder—the New York 16-year-old who was arrested on robbery charges in 2010, held in solitary confinement for years without a trial, and eventually committed suicide—the idea of inmate isolation as a viable form of state-sanctioned imprisonment has come under severe criticism. But more on that later.

In the early to mid-19th century, the emphasis on solitary confinement and moral redemption embodied in the Pennsylvania system became a national and then global model for incarceration. Hundreds of prisons around the world came to be modeled after the Eastern State Penitentiary. This phenomenon—the influence of the Pennsylvania philosophy on the development of prisons around the world—foreshadowed a sort of complex within the Prison Industrial Complex itself. That is, political leaders, partnerships between public and private enterprises, and the powerful influence of the burgeoning institutional model on the development of prisons, globally signaled a capacity to determine society's sense of what prisons should do and be. The American prison model would ultimately occupy a powerful space in the global social contract. According to one critic of the prison/crime industry, Nils Christie, contemporary “American criminology rules much of the world, their theories rule much of the world, their theories on crime and crime control exert enormous influence.”14

The central idea of the Pennsylvania system was that reforming criminals in isolation was both possible and more useful to the greater societal good than simply punishing and/or killing them. The fact that this debate, with its deep philosophical questions regarding the purpose of prisons, was situated in the very origins of the American penal instit...