![]()

part 1

The Home Front

![]()

1

We Are All Home-Front Soldiers Now

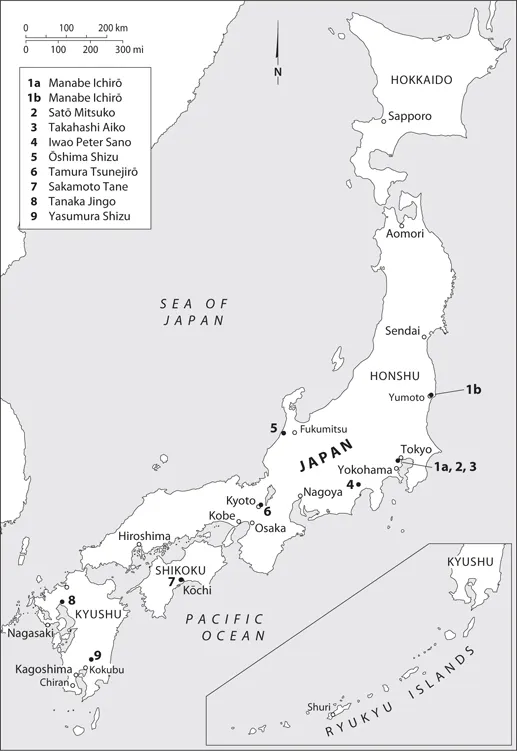

Japan had done much to prepare its people for war. By December 7, 1941, the country had been at war for almost three and a half years already. This began in July 1937 when men from a Japanese army unit stationed outside Beijing provoked a firefight with Nationalist Chinese troops, and the Japanese government used the incident as a pretext for invading China. Japanese forces then streamed into north China from Korea, a Japanese colony, taking both Beijing and Tianjin by the end of the month. In November the Japanese opened a second front in Shanghai and took that city and then Nanjing, committing horrible atrocities in the process. A year later, Japanese forces had taken Guandong and Wuhan, and by December 1938 they controlled all of the Chinese littoral, and Chiang Kai-shek had moved the Nationalist government to Chongqing in southwestern China. During the first three years of the war, the Japanese military drafted nine hundred thousand men, and more than a million Japanese servicemen were stationed overseas at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941.

Popular support for war existed well before July 1937. The Japanese takeover of Manchuria (1931–1932) generated what historian Louise Young terms “war fever” and “imperial jingoism,” which, she points out, was the work of the commercial media, particularly the newspapers and radio.1 Indeed, the government seemed to have learned something from them, and perhaps even from the Nazi regime in Germany, because beginning in January 1938, ten minutes of war news was broadcast every night at 7:30 p.m.2

Even before the outbreak of war in China, the government had taken steps to control the media, by reducing the number of newspapers and magazines, creating new government agencies to oversee the press and manage news reporting, and issuing new guidelines for reporters.3 Then the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, journalists were urged to write articles about Japan’s military superiority, its enmity for the United States and Britain, and the prospects for a long war.4

With the outbreak of war, the Home Ministry initiated a series of spiritual mobilization campaigns designed to generate popular support for the war. These assumed many forms: citizens were encouraged to avoid extravagance and to save for themselves and the state; women from the National Defense Women’s Association sent off recruits, made talismanic thousand-stitch belts for them to wear in battle, and enlisted schoolgirls to write letters to servicemen serving overseas; and streetcars paused in front of the imperial palace so that passengers could bow to the emperor. On the first anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident that opened the Sino-Japanese War, the Asahi newspaper sponsored a parade of ten thousand patriotic citizens that went from Yasukuni Shrine to the imperial palace.5

The Ministry of Education also created what might be called an “official ideology.” Taking the lead, it published in the mid-1930s a fourth edition of ethics textbooks that was decidedly more nationalistic and militaristic.6 This edition was guided by a new pedagogical strategy: the children were now “to be affected on an emotional level,” as education ministry policymakers put it. A fifth edition, published during the war, simply intensified the changes initiated in the fourth edition.7 Even more telling were the government agencies’ statements of the official ideology for popular consumption. In 1937 the education ministry published Kokutai no hongi (The Principles of Our National Polity), intended for teachers, and Shinmin no michi (The Way of the Subjects), disseminated among the general population. In 1941 the war ministry issued the Senjinkun (Field Service Code), which laid out the ideal values and behaviors of servicemen, including the no-surrender clause that would lead many thousands of Japanese servicemen to commit suicide rather than surrender. Every serviceman was expected to memorize the Senjinkun and follow its precepts.

In 1940 the Home Ministry began mobilizing the entire home-front population, as well as Japan’s colonial subjects, for the war. It created new organizations called “community councils” (chōnaikai). In the cities each council consisted of a few hundred households, and in the countryside they consisted of whole villages. By the end of the year, more than 180,000 of these bodies had been formed.8 In addition, the Home Ministry created neighborhood associations (tonarigumi), subordinate to the community councils. Because this was a much larger task, it took longer to implement, but by July 1942 there were more than a million neighborhood associations in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea, each consisting of eight or nine households.9 By design, the functions of the two organizations overlapped slightly: the community councils relayed government policy to neighborhoods and discussed the topics to be addressed by neighborhood associations, which included air defense, savings bonds, metal collection drives, comfort kits for servicemen, and commemorative rituals and events.10 The neighborhood associations met several times a month to discuss issues that the home ministry relayed to them through the community councils—issues such as food rationing, the distribution of commodities, the collection of materials for the war effort, savings-bond campaigns, air defense, and labor service. Typically, each family sent a representative, usually the mother of the household, to these meetings, which started after dinner and often lasted until just before midnight.

The government’s first step in transforming the domestic economy into a war economy was to create a “new economic order,” which included control over the import and export of crucial raw materials. In 1938 the gover...