1

CHINA’S RELATIONS WITH DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA

The greatest friend of the Kampuchean people is the People’s Republic of China, and none other. The People’s Republic of China is the large and reliable rear fallback base of the Kampuchean and world revolutions.

—Kaev Meah, veteran Cambodian Revolutionary, September 30, 19761

The Chinese government never took part in or intervened into the politics of Democratic Kampuchea.

—Zhang Jinfeng, Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia, January 22, 20102

When people mention the Khmer Rouge, many might be reminded of the support China once gave it. This is a problem that cannot be avoided. No matter whether China wants it or not, as China’s relationships with Cambodia and Southeast Asia grow closer, people will allude to that history.

—Ding Gang, September 27, 20123

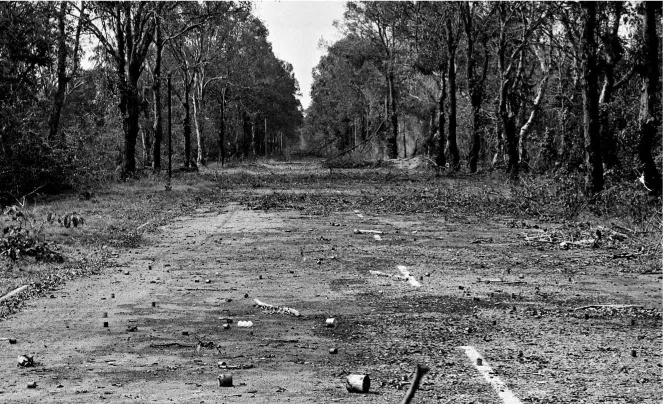

A particularly haunting Vietnam War–era photograph, taken by the Japanese photojournalist Taizo Ichinose, who would himself perish behind enemy lines in 1973, shows the road leading to Angkor Thom, the twelfth-century epicenter of Cambodian civilization that today is a bustling tourist site.4 The road is covered in detritus from the forest and is devoid of any trace of people—but for a human spinal cord mixed in with the debris (fig. 1.1).5 There is nothing romantic about the image: this jungle evokes Carthage, not Walden. It is as ugly and grotesque an image of a rural setting as can be imagined, one that also perfectly captures the atmospherics of Hobbes’s state of nature—the absence of any governing apparatus whatsoever. It is a snapshot of anarchy.

People tend, not unreasonably, to regard Cambodia’s rule by the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK)—commonly known as the Khmer Rouge—from 1975 to 1979 as one in which the only thing that distinguished the country from such anarchy was its sophisticated killing apparatus.6 This is not quite right. The CPK-led regime of Democratic Kampuchea (DK) is rightly understood, first and foremost, as a regime that killed a vast number of its own citizens and horribly brutalized those it did not murder outright. But it does not necessarily follow that, if we peel away its extensive security apparatus, DK resembled a country-sized extension of Taizo’s terrible image. That is, DK was not defined by the negative space of anarchy. It was a state. It was a totalitarian state. It was often a poorly run totalitarian state. It was a state that excelled at fear, death, and hubris far better than anything else. But it was a state defined by a distinctive network of organizations and institutions, not the absence of them.

FIGURE 1.1. The road to Angkor Thom. Photo by Taizo Ichinose.

There is also a historic context to this image that hints at the role of China in the narrative to follow. At the time this photo was taken, not far away at Mount Kulen, the deposed Cambodian monarch Norodom Sihanouk was meeting with the CPK leadership in the latter’s jungle headquarters, a rendezvous that had been insisted upon by the government of China. Sihanouk headed a coalition government (Gouvernement Royal d’Union Nationale du Kampuchéa, or GRUNK) brokered by Beijing that, in just three years, saw the transformation of the CPK from a junior partner with a few dozen rifles in 1970 to the coalition’s dominant power.

China had been involved in every aspect and at each stage of the CPK rise to power. From 1970 to 1975, Beijing provided GRUNK with an annual budget of US$2 million as well as office space and living quarters at the Friendship Hotel in northwestern Beijing, while Sihanouk himself took up residence at the former French Embassy. Even the Chinese mission to Phnom Penh was physically relocated to Beijing, where the Chinese ambassador to Cambodia, Kang Maozhao, carried out his functions as if he were on Cambodian soil.7 Beijing continued to provide arms, clothing, and food and even printed banknotes for use upon the CPK’s assumption of power. And as relations between the Cambodian and Vietnamese communists began to sour, China’s support for the CPK insurgency correspondingly increased.

After April 17, 1975, when victorious CPK soldiers marched into Phnom Penh and other cities throughout the country, the world of many Cambodians was turned upside down: cities were emptied of their residents, who were forcibly relocated to the countryside; markets disappeared; money was abolished (the banknotes printed in China were mothballed); officials of the ancien régime were liquidated; and China’s influence was radically altered. Up to that point, Beijing had been both willing and able to graft its strategic interests onto the political evolution of the CPK. After 1975, China’s apparent willingness to continue doing so never wavered; its ability to do so, however, decreased significantly. To put it somewhat inelegantly, China embraced a sucker’s payoff in a Faustian bargain: it justifiably received international condemnation for maintaining the viability of the CPK regime while receiving precious little tangible benefit from its Cambodian allies. And this provides the central question of this book: why was a powerful state like China unable to influence its far weaker and ostensibly dependent client state? Or, to put it in policy terms: exactly what did Chinese development aid buy?

In today’s world, as the topic of Chinese foreign assistance grows in importance, the answers matter. The conventional wisdom holds that a rapidly-developing China is currently behind a new wave of economic colonialization, facilitated and nurtured by Chinese foreign aid and assistance. This has raised alarm bells both in these “colonies” themselves8 and in the policy circles of Washington, D.C., which have seen an emerging consensus that such foreign policy behavior is a manifestation of China’s inexorably rising power on the international stage.9

This is not inconsistent with the received wisdom on Sino-DK relations. One conventional view is that the relationship was a product of a shared revolutionary outlook and a natural affinity based on the similarities of experiences in the two regimes’ paths to power. It argues that DK leader Pol Pot was himself greatly influenced by events in China, some of which—particularly the opening salvos of the Cultural Revolution in 1965—he witnessed firsthand, and by his friendship with Chinese officials like the mysterious and amoral radical Kang Sheng, whose own training in the USSR during Stalin’s Great Purge fashioned him into China’s Lavrentiy Beria.10

Another approach, based on Realpolitik, posits that Beijing’s relations with Phnom Penh were a function of regional geopolitics, a product of the Sino-Soviet split, Hanoi’s increasing dependence on Moscow, and the race between Vietnam and China for U.S. diplomatic recognition.11 Aside from the sterilizing effect this has on some fundamental normative issues regarding collaboration with the DK regime, this level of analysis tells us little about the actual mechanics of the relationship. Such an approach cannot account for variation in the success or failure of individual assistance projects.

The two lines of argument share the assumption that Beijing, as a regional and a nuclear power, was able to influence a small, poor, overwhelmingly premodern (indeed, medieval) agricultural state of seven million. They do not—cannot—account for China’s failure to exploit this asymmetrical relationship. As a result, we are left with an empirical and historical fact bereft of explanation or context.

Still another approach, this one ideational, can be found in Sophie Richardson’s China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, which centers on Chinese motivations, that is, the “five principles” themselves—mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, nonaggression, noninterference in the internal affairs of others, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence.12 Although Richardson makes a persuasive case for Beijing’s subordination of some of its own interests to the larger contours governing the relationship, her analysis is not engineered to evaluate China’s concrete gains from the relationship.

By contrast, the argument in this book will show that in the deeply uneven bilateral relationship, on the policy front at least, it was in fact China that ended up as the subordinate party. Before explaining why this was so, it may be useful to show that the political history of China’s relationship with Democratic Kampuchea confirms that the expected outcome—a relationship in which Beijing dictated critical strategic terms to Phnom Penh—never came to pass.

Dynamic Interaction in Sino-DK Relations

For decades China had supported the Vietnamese communists against the French and then against the United States, but as the fraternal socialist ties between the two countries gave way to traditional mistrust spawned from centuries of Vietnamese armed resistance to Chinese regional hegemony, Beijing’s suspicions of Hanoi mounted. In 1969, Beijing’s relations with Moscow had reached their nadir, when Chinese and Soviet troops stopped just short of limited war along their isolated border in Siberia. By 1975, the prospect of China being boxed in to the north by the USSR and to the south by Moscow’s ally Vietnam was becoming increasingly troubling to China’s leaders. The establishment of DK in April of that year was an opportunity for China to mitigate the effects of a Soviet-Vietnamese axis. The CPK’s growing hostilities against Vietnam, also borne of centuries of ethnic tensions that often erupted into gruesome violence, ensured Phnom Penh’s distance from Hanoi and Moscow. The United States, suffering at the time from “Indochina fatigue” after what had been the longest war in its history, largely stayed clear of the fray.

Within days of the fall of Phnom Penh on April 17, Chinese aid in the form of food and technical assistance started arriving.13 A string of official visits began as well. On April 24, Xie Wenqing, a reporter from the international desk of the New China News Agency (Xinhua), arrived in the Cambodian capital. Four days after that, DK Foreign Minister Ieng Sary returned from China, where he had been living on and off since 1971, accompanied by Shen Jian, deputy director of the CCP International Liaison Department and Beijing’s point man on Democratic Kampuchea.14 On June 21, on a secret visit to China to secure military and nonmilitary development aid, Cambodian leader Pol Pot himself met with Mao Zedong.15 At the time, Mao’s commitment of one billion dollars was the largest aid pledge in the history of the PRC.16 In August, a delegation from the PRC Ministry of National Defense visited Cambodia to survey DK military needs, followed by a visit by Wang Shangrong, deputy chief of staff of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA), in October.17

At the same time, DK began the first wave of political purges, a campaign to liquidate the old exploiting classes—monks, urban bourgeois, intellectuals, and officials of the Khmer Republic. This development was startling enough for ailing, cancer-stricken Zhou Enlai to warn visiting DK officials Khieu Samphan and Ieng Thirith that they should avoid making the same mistakes of immoderation that China had made in the not-so-distant past. Flush with victory, his guests are reported to have smiled at him condescendingly.18

A thornier issue was how to handle Sihanouk. The prince, whom many of Cambodia’s peasants regarded as a living god, had done more than any other individual to legitimize the CPK. Ousted in the March 1970 action that established the Khmer Republic, the mercurial Sihanouk quickly embraced his former enemies, the Khmer Rouge.19 After returning to Cambodia in 1975 from a world tour promoting the new regime and finding himself unhappy as a figurehead, Sihanouk sought to retire. Although the top DK leadership was happy to sideline the prince, whom they referred to as “a runt of a tiger bereft of claws or teeth [with] only his own impending death to look forward to,” they feared alienating Beijing.20 From the mid-1960s onward, Sihanouk had enjoyed a particularly good relationship with China’s top leaders, including Mao, Zhou, and Liu Shaoqi. He even provided a unique “model” for Chinese leaders to cultivate among the nonaligned developing world: a left-leaning royal sympathetic to China.21 During a hasty set of meetings from March 11 to 13, 1976, the DK leadership accepted Sihanouk’s resignation while severing any contacts between the prince and visiting foreign delegations, particularly from China; this affected such dignitaries as Zhou Enlai’s widow, Deng Yingchao, whose request to meet with Sihanouk on a January 1978 visit was denied.

In April 1976, radical leftist Zhang Chunqiao made a secret visit to Cambodia. One top DK Foreign Ministry official said he would not have known about the visit if he had not noticed some children making a welcoming banner for Zhang (as this was a CCP-to-CPK visit, it is not surprising that the Foreign Ministry was kept in the dark). Zhang’s purposes in visiting were to demonstrate the Gang of Four’s support for Democratic Kampuchea and to assess the situation in the country.22

Meanwhile, following a lull in early 1976, aid picked up again, including plans to build a secret weapons factory just outside Phnom Penh.23 According to a 1976 DK report, China had committed to shipping one thousand tons of military hardware to DK, including tanks and other military vehicles, ammunition, communications equipment, and other materiel.24 Accompanying this rise in imports was a shift toward domestic economic development through the adoption of a Four Year Plan (1977–1980) along with a new wave of purges, this time focusing on political malfeasance within the regime, particularly but by no means exclusively the cadres of the Northwest Zone. Once again, Beijing chose not to notice.

Did the death of Mao Zedong in September 1976 and the arrest of the powerful leftist faction by Mao’s more moderate successor Hua Guofeng one month later provide China with some potential leverage to compel the DK leaders to show a little restraint? Legal scholar John Ciorciari believes so. Pol Pot demonstrated his pragmatic streak when he denounced the “counter-revolutionary Gang of Four anti-Party clique” and demonstrated his support for Hua’s actions.25 But Beijing, refraining from exploiting its leverage, did not discontinue its unconditional aid. On December 10, 1976, a delegation of Chinese journalists led by Mu Qing, deputy chief of Xinhua, visited the country, meeting with the soon-to-be-purged Minister of Propaganda, Hu Nim. Two weeks later, from December 24, 1976, to January 2, 1977, a delegation from the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations led by Fan Yi met with DK economic czar Vorn Vet.26

China did, however, succeed in getting Pol Pot to abandon his tendency toward excessive secrecy and introducing him to the wider world in a...