![]()

Chapter 1

Islam in the Eyes of the West

Islam as Part of the Contemporary World

For more than thirty years I have been convinced that the greatest contemporary gap in understanding lies between the majority of Americans and Europeans—the so-called West—and the rest of the world. As an American exposed to international experience early (I spent a year as an exchange student to Chile at age sixteen), I came to realize that despite their many virtues, Americans are not very good at understanding other cultures. This gap in understanding is largely a one-way affair. That is, in the process we now call globalization, the products of American and European culture are broadcast to every country in the world. As a result of the era of European colonialism, languages such as French, Spanish, English, Portuguese, and Russian are the most prestigious vehicles of education and mass communication throughout Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. In contrast, it is possible for educated Americans and Europeans to ignore Chinese, Hindi-Urdu, Arabic, Bengali, and Malay-Indonesian with perfect equanimity, even though more people today speak these non-European languages.1 While American and European authors, artists, and actors are known throughout the world, it has been a rare occurrence for an Asian, Middle Easterner, or African to obtain this kind of status.

Although globalization has been seen as the defining process of our time, we seem to be uneasy and confused about what kind of world we actually live in. It used to be that we spoke of three worlds: the First World, consisting of economically and technologically developed nations, primarily the United States, Europe, and Japan; the Second World, mainly the former Soviet Union and its Communist allies; and the Third World, the poor and underdeveloped countries of Asia, Africa, and the Americas. It has been more than a decade since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet empire, so the Second World evidently no longer exists. How many worlds are left?

Conventional wisdom has it that, despite the demise of the USSR, there is still a confrontation of the West against the rest. The chief spokesperson for this viewpoint in recent years has been Samuel Huntington, whose provocative article “The Clash of Civilizations” became a widely read book.2 His thesis, based on a superficial and tendentious reading of history, claimed that there are a given number of civilizations (up to eight, in theory) that will inevitably clash until one emerges triumphant. After eliminating the least important of these civilizations, he concludes by postulating an eventual death struggle between the progressive West and the retrograde Islamic world.

This argument was met with dismay and concern among intellectuals and political leaders in majority Muslim countries. Only a few years ago most of these countries lay under European colonial domination, the result of aggressive European military expansion in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia since the days of Napoleon. Would this argument be used to unleash new military adventures against the enemies of “the West”? Significant voices were raised to refute this confrontational position. President Khatami of Iran responded by proposing an alternate view, which he called the “dialogue of civilizations.” The United Nations adopted the formula of dialogue of civilizations as a theme for worldwide discussions in 2001.

The fact is, as American Islamic studies specialist Marshall Hodgson pointed out long ago, there has not been a separate “Muslim world” for more than 200 years. Politically, economically, culturally, and of course militarily, the fates of majority Muslim countries have been closely tied to Europe and America throughout this period. International financial networks, multinational corporations, media conglomerates, and the Internet have now created a world in which it is impossible to keep one culture isolated from the rest. If one looks at the more than fifty nations that have a majority Muslim population today, one is forced to confront a bewildering diversity of languages, ethnic groups, and differing ideological and sectarian positions (though the flow of information can still be largely in one direction). In the heart of “the West,” there are today at least 5 million American Muslims and 10 million European Muslims. So why do we continue speaking of “the Muslim world” in opposition to “the West,” when such a concept is out of step with reality? Do we really wish to condone the notion that there are two violently opposed worlds struggling for global domination? The extraordinary mismatch between Euro-American ideas of Islam and the realities lived by Muslims will form a recurring theme throughout this book. There is no one simple or easy explanation, though one must look both at history and at contemporary political interests to see the larger patterns.3

To begin with, it may be helpful to ask how we define “the West,” or “Western civilization,” since this phrase has no obvious geographical meaning if it includes territories as far apart as North America, Europe, and possibly Japan. As an explanation, I would put forward an academic ritual in which I was involved some twenty years ago, when as a first-year professor at Pomona College in Claremont, California, I was asked to take part in the Ceremony of the Flame. The basic structure of this ceremony was simple: a series of individuals, beginning with the chairman of the Board of Trustees, enacted a flame-passing ritual, in which the flame of knowledge and enlightenment was transmitted to the college president, a senior faculty member, a new faculty member (me), a senior student, and finally a lowly first-year student (this was originally done with lit candles but, for safety reasons, was now performed with battery-operated, candle-shaped lights). Meanwhile, an announcer read a short passage explaining the ceremony, starting with the phrase, “In the beginning, there was light.” With obvious religious overtones referring to both Genesis and the Gospel of John, the narration went on to describe the gradual westward movement of this light of knowledge, until it ultimately reached its destination in the foothills of Southern California. Simultaneously, college officials symbolically passed this knowledge on to students.

Although the example may seem eccentric, it presents the essential outlines of the concept of Western civilization that is transmitted to millions of American students through history textbooks, and which is believed by many to be the essence of our culture and society. The typical sequence of this civilization’s development begins briefly in Mesopotamia and Egypt before heading to Greece, where it really gets started. It is important to notice that, as civilization moves west, its preceding locations fall out and become irrelevant. After Greece declines, then comes Rome, followed by the gradual ascendancy of France, Germany, and possibly Spain. But (at least in American versions) the next destination is definitely England, followed ultimately by America as its ultimate goal. The special twist that makes California the apex of Western civilization is disputed, however, in places like New York.

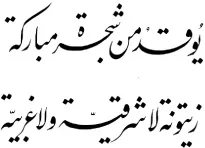

Presented in this manner, the concept of Western civilization may appear ludicrous. More seriously, one might say that the defining characteristics of Western civilization are considered to derive from two sources: Israelite prophecy and revelation, on one hand, as a source of ethics and religion, and Greek philosophy and reasoning, on the other, as the basis of both science and democracy. As a straightforward historical description, this account of the origins of European civilization seems reasonably accurate. Nevertheless, if we attempt to come up with a parallel definition for Islamic civilization, we are presented with a predicament. The Islamic tradition also claims to be based on the same two sources, the prophets of Israel and the philosophers of Greece. The Qur’an acknowledges a long line of prophets including Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. Greek philosophy and science, moreover, were subjects of intense study in the lands ruled by Muslim caliphs when they were barely known in Christian Europe; it was only due to translations from Arabic into Latin that Aristotle was rediscovered in Paris and Oxford. Philosophy continued to undergo significant development, particularly in Iran and India, up to modern times (although this has been largely unknown outside specialist circles). The European and American claim to exclusive ownership of the two main sources of civilization is therefore historically false. There were also important countertrends in the symbols of civilization that moved east instead of west. After Rome itself had fallen to barbarian conquest, Constantinople (also known as Byzantium) was the capital of the ongoing Roman Empire. When the Ottoman sultans conquered Constantinople in 1453, they themselves self-consciously took on the mantle of the Roman Empire; although Western Europeans knew them as Turks, to their Arab subjects in the Near East they were simply “the Romans” (“Rumi,” or “Arwam” in the plural).

This kind of cultural myopia and chauvinism is not limited to Europeans, to be sure. Writing in North Africa in the late fourteenth century, the great Arab historian and philosopher Ibn Khaldun observed that he had heard rumors that, among the northern Frankish barbarians (i.e., European Christians), there were some who were interested in philosophy, but he had never seen any proof of this. Doubtless this remark would have been highly offensive to European philosophers of the day, had they been able to read it. Today, in any case, it is no longer defensible to take refuge in ignorance as an excuse for making exclusive claims to civilization. By excluding Muslims from Western civilization, Europeans and Americans are claiming a questionable identity. Excluding Muslims from European culture in general also runs counter to history. Despite the expulsion of the Moors and Jews from medieval Spain, and the nationalistic rejection of the “Turkish yoke” in southeastern Europe in the nineteenth century, Islam has been a defining factor in European culture for more than a thousand years.4

Ultimately, Huntington’s clash of civilizations should be seen as a reversion to colonial doctrines of European supremacy. It lacks the overt dependence on racial theory that was fashionable in the nineteenth century, but it shares the basic prejudice of reserving true civilization for Europe, which is opposed by barbarism everywhere else. The technical edge that gave Europe military superiority over the rest of the world is mistaken for cultural superiority. The 1910 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica summed up this attitude perfectly in its article on Asia written by a British colonial official:

While it might be conceded that most religions originated in Asia, Christian Europe had managed to cut itself clear of those origins:

In its own day, this colonial rhetoric of European supremacy served as a justification for conquest and domination of the rest of the world. It is understandable that Huntington’s similar thesis should cause alarm among those who are excluded from his vision of the West.

At the same time, it cannot be denied that there have been powerful voices from Muslim countries in recent years stridently proclaiming the eternal opposition of Islam and the West. What is the reason for these claims, and why should they not be given credence? My assumption throughout this book is that every claim about religion needs to be examined critically for its political implications. Religion is not a realm of facts, but a field in which every statement is contested and all claims are challenged. Religious language in the public sphere is not meant to convey information but to establish authority and legitimacy through assertion and persuasion. The Eurocentric prejudice against Islam needs to be understood as a historical justification for colonialism. In the same way, the recent use of Islamic religious language against the West should be seen as an ideological response against colonialism that deliberately uses the same language.

Religious language expressed on a mass scale is essentially rhetorical. Sweeping religious statements of extreme opposition should not be accepted on face value, especially since they generally have immediate political consequences. One always has to ask the lawyer’s question about this kind of language: Who benefits from it (cui bono)? In statements that attribute political differences to fundamental religious positions, the implicit conclusion is that there is no possibility of negotiation, because religious positions are eternal and unrelated to passing events. This is convenient to both extremes in a violent struggle. On one hand, extremist movements in opposition to the state can describe their struggle as a religious quest mandated by God. Even if the extremists are few, by making such absolute claims they can justify any action, no matter how violent, because their struggle is based on truth and the fight against evil. On the other hand, governments that wish to eradicate dissent find it convenient to label their opponents as religious fanatics; this relieves governments of the responsibility to deal with legitimate grievances, because their opponents may be dismissed as irrational and incapable of responding to reason. Examples of this kind of religious rhetoric can be found in many situations ranging from Israel and Egypt to Waco. Those who attribute conflict to religion, whether they speak as opposition figures or as state authorities, do not speak for the vast majority of religious people, and indeed they contradict the history of religion. But such is the power of the mass media that these violent messages of religious opposition are carried to every corner of the world, with a powerful and persuasive effect.

Historically, there are reasons why the religious language of Islam became a vehicle for political opposition. Over centuries of colonial rule, many Far Eastern countries enthusiastically converted to European doctrines, whether Catholicism in the Philippines under Spanish rule, Protestant Christianity in Korea, Marxism in China, or the doctrine of progress and modernization in Japan. The Hindu tradition of India was in a defensive posture in the nineteenth century, under critique from British colonial administrators and Christian missionaries. Mohandas Gandhi’s nonviolent nationalism, although it drew on Hindu teachings, embraced religious pluralism and a secular Indian government. Only in recent years has a Hindu fundamentalist identity emerged in India, in part as a deliberate response to Muslim fundamentalism as well as to Christian missionaries. Buddhism, though strong in certain national contexts like Sri Lanka and Tibet, was not as easily adapted to mass political movements. Apart from the Islamic tradition, one searches in vain for another indigenous symbolic resource that could furnish Asia or Africa with an easily adaptable ideology of resistance.

In some ways, the recent prominence of the word “Islam” indicates a momentous shift in religious thought, dating from the early nineteenth century. In the scale of values found in traditional theology, the Arabic term islam was of secondary importance. Meaning “submission (to God),” islam effectively denoted performing the minimum actions required in the community (generally defined as profession of faith, prayer, fasting during Ramadan, giving alms, and performing pilgrimage to Mecca). Much more important for religious identity was “faith” (iman), described as believing in God and everything revealed through the prophets, and all the debates of theologians revolved around how to define the faithful believer (mu’min). But the term “Muslim,” meaning “one who has submitted (to God),” always had a corporate and social significance, indicating membership in a religious community. “Islam” therefore became practically useful as a political boundary term, both to outsiders and to insiders who wished to draw lines around themselves.

Historically, Europeans had used the term “Muhammadan” to refer to the religion of followers of the Prophet Muhammad, although Muslims regard that as an inappropriate label.6 The term “Islam” was introduced into European languages in the early nineteenth century by Orientalists such as Edward Lane, as an explicit analogy with the modern Christian concept of religion; in this respect, “Islam” was just as much a newly invented European term as “Hinduism” and “Buddhism” were.7 The use of the term “Islam” by non-Muslim scholars coincides with its increasing frequency in the religious discourse of those who are now called Muslims. That is, the term “Islam” became more prominent in reformist and protofundamentalist circles at approximately the same time, or shortly after, it was popularized by European Orientalists. So in a sense, the concept of Islam in opposition to the West is just as much a product of European colonialism as it is a Muslim response to that European expansionism. Despite appeals to medieval history, it is really the past two centuries that set up the conditions for today’s debates regarding Islam. Comprehending the process that led to this language of opposition is an essential task for understanding this single world that we all share.

Anti-Islamic Attitudes from Medieval Times to the Present

It is safe to say that no religion has such a negative image in Western eyes as Islam. Although it would be pointless to engage in competition between religious stereotypes, one can certainly see Gandhi and his advocacy of nonviolence as a positive image of Hinduism. Likewise, the Dalai Lama has an amazingly positive and widespread recognition as a representative of Buddhism. Europe and America have done a dramatic about-face with respect to Judaism over the course of the past century. Although anti-Semitism was common and even fashionable early in the twentieth century, the horrors of the Holocaust and the establishment of the state of Israel changed that. While anti-Semitism still lingers among certain hate groups, there are plenty of defenders of Judaism on the alert against them. Christianity, of course, remains the majority religious category in most of Europe and America, and it is n...