![]()

Chapter 1 The Land Regime in Late Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine

Introduction

Palestine in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was a predominantly agricultural region. Man-made impositions and natural impediments restrained Palestine’s economic growth. Rapacious tax demands, the malfeasance of local Ottoman officials, and traditional methods of land utilization discouraged agricultural development. The decline in plow and grazing animals, the dearth of investment capital, and World War I’s disruption of foreign and domestic agricultural markets, all exacerbated by the retreating Turkish armies, left Palestine’s agricultural economy devastated by 1918.1

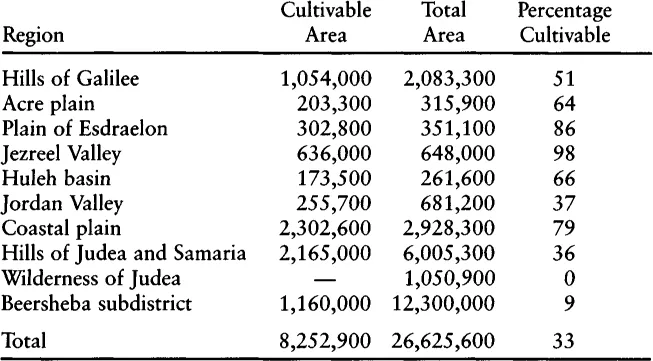

The strength of Palestine’s economy was limited by the land areas capable of cultivation. The land in the Palestine region, like other areas of the Fertile Crescent, was under heavy agricultural use for millennia. Soil quality declined because of salination of water tables, deforestation, predatory raids, and a wide variety of other factors. Though the total land area of Palestine was estimated at 26.3 million dunams,2 less than a third of it was considered cultivable (see Table 1). The remainder was dotted by intermittent mountain ranges, sand dunes, bleak terrain, alkaline soils, semiarable regions, obstructed water courses, and marshlands. Palestine’s topographical features and poor soil contributed to paltry crop yields on which its rural population barely subsisted. In a society in which control or ownership of land was the chief source of relatively stable wealth and position, control of this limited amount of fertile and cultivable land also became the essential criterion for prestige and influence. One’s relationship to land reflected one’s political, economic, and social weaknesses and strengths.

In the emerging effort to establish a Jewish national home, the area of Jewish land acquisition focused almost exclusively on the cultivable plain and valley regions of Palestine. Thus, in the quest to establish a territorial nucleus for a state, the Zionists sought to purchase a substantial portion of these regions totaling about 9 million dunams of land. By 1948, at the end of the British Mandate in Palestine, Jews had acquired approximately 2 million dunams of land, mostly in the valley and coastal areas.

TABLE 1 Total Cultivable Land Area (in Metric Dunams) of Palestine in 1931

Source: The statistics for Table 1 were gathered by Maurice Bennett, who was seconded to Sir John Hope-Simpson’s staff in 1930. As commissioner for land and surveys, Bennett sent these statistics to the Jewish Agency in 1936. See his dispatch of 9 October 1936, Central Zionist Archives, S25/6562.

In 1918, the economic outlook for Palestine’s rural Arab population, estimated at 440,000,3 was very uncertain. The cultivated land was not very fertile or sufficiently irrigated. The failure or inability to use modern agricultural techniques such as manuring and mechanization kept yields to a minimum.4 Crop rotation was rarely practiced. A severe shortage of livestock had resulted from a prewar epidemic and Turkish requisitioning of camels and sheep from 1914 to 1917. Conscription had depleted the agricultural labor supply. The massive destruction of olive trees by the retreating Turkish forces compounded the agricultural population’s woes. Uncertain validity or absence of land titles hindered the granting of loans, particularly in the administrative turmoil created by World War I. Historically, during periods of economic and physical insecurity, the Palestinian agricultural laborers, or fellaheen (fellah, sing.), migrated from the coastal or maritime plain to the central range of hills running from the Galilee in the north through Hebron in the south.5 Jewish immigration and land purchase occurred at a time when the cultivated regions suffered a measure of depopulation resulting from economic hardships, conscription, and local instability.

In 1918, the nature of Palestine’s land regime derived from Ottoman inheritance. Most patterns of behavior and social norms within the Arab community transcended the shift from Ottoman to British administration, and it was attended by very little change in the political, economic, and social status quo of the Arab community living in Palestine. No new elites emerged. The loose and unexacting authority of the Ottoman central government had slowly enabled local administrators, merchants, religious leaders, and others to control the administrative structures in “Greater Syria” and therefore in Palestine as well. Arab politics in Ottoman and early Mandatory Palestine relied upon kinship, close family ties, village identity, and personal connections.

What changed, however, with the advent of British administration was the institution of a more efficient and watchful administrative structure, which had an ultimate impact upon the evolution of the Arab community of Palestine. British control over the land regime deprived large landowning families of their customarily unchecked means to financial advancement. British administration blocked individuals who had previously accumulated land during the Ottoman regime through privilege, access to information, and informal political structures. Tax collection and land registration under official British purview denied this segment of the notable class their uncircumscribed means of acquiring more land. The severely damaged agricultural sector and diminished yields had resulted in a decrease in rental incomes and therefore less capital accumulation. No longer able to use the Ottoman modalities of operations, numerous Arabs in Palestine chose to sell land to individual Jews and immigrant Zionists as a convenient alternative for ready cash.

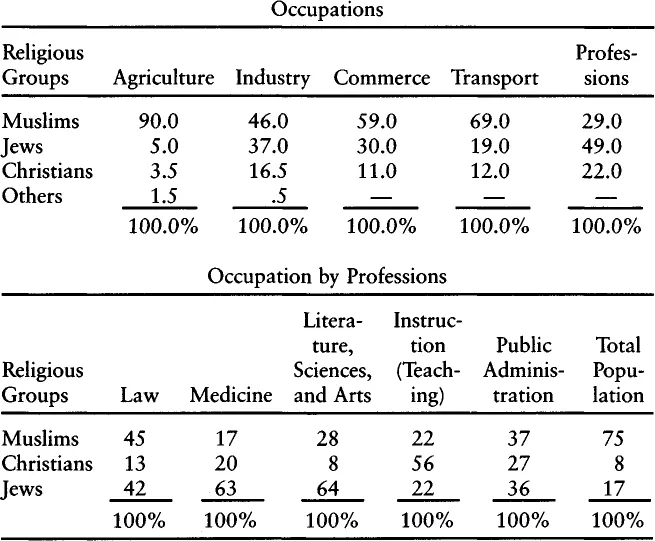

But only gradually did the British presence and administration in Palestine alter the fabric and relationships within Arab society and contribute to increased Jewish presence. Change came slowly in the early 1920s for several reasons. First, the habits inherited from the Ottoman land regime were deeply entrenched in custom and tradition. The fellaheen population had shown a clear aversion to government association because of an abusive and unchecked taxation system. Fellaheen distrust of government was compounded by the fear of conscription. These fears were carried over into the Mandate by an overwhelmingly illiterate and unsophisticated peasantry that had no interest in political involvement, was not cognizant of its legal rights, and did not have any promise of financial betterment. At the other end of the Arab social spectrum, there were relatively few large landowners from whom the early Jewish immigrants bought land. According to the Census for Palestine, 1931, out of the total Muslim earning population, only 5 percent was engaged in intensive agriculture and only 4 percent derived its livelihood from the rents of leased agricultural lands.6 Table 2 provides additional information about the relationship between occupation and religious affiliation in Palestine for 1931.

TABLE 2 Occupations of Religious Groups in Palestine in 1931 (in Percentages)

Source: These statistics have been culled from various portions of the Census for Palestine, 1931, because it was the most complete data assembled during the Mandate.

Second, the Zionist community in Palestine, though buoyed by the Balfour Declaration of November 1917 and the prospects of a Jewish national home, was only in the incipient stages of organizational development. Resources were scarce and Jews constituted only 10 percent of the total population of Palestine. Though the Jewish community received through the articles of the British Mandate special consultative privileges not enjoyed by the Arab community, its relationship with the British required definition and refinement.

The establishment of a Jewish national home was part of the context within which His Majesty’s Government (HMG) was attempting to protect its strategic interests in the Middle East. Maintaining its presence in Egypt, assuring access to the Suez Canal and the East, preventing French ambitions in Lebanon and Syria from drifting south, and creating a land bridge from the Mediterranean Sea to the oil fields of Iraq all entered HMG’s calculus. But in securing and controlling Palestine, HMG demonstrated little understanding of the Zionist commitment to create a Jewish national home or of the Arab community’s economic plight. This lack of understanding contributed directly to a hastening of communal separation, physical violence, the idea of creating separate Arab and Jewish states in 1937 and 1947, and the creation of Israel in 1948.

Elite Continuity

Up to 1839, Ottoman administration in Palestine had concentrated on the preservation of Ottoman supremacy, revenue collection, and security for the hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca. The gradual decline of the central government’s power, accompanied by the development of autonomous authority in the provinces, forced the Ottoman administration to reform its provincial administration. The tanzimat, introduced to spark state building in the Ottoman Empire, involved a variety of reform efforts including the assurance of revenue collection and its successful remittance to Istanbul. Stability in any region of Palestine meant establishing an atmosphere that would encourage continuous cultivation of land and effective collection of taxes. In the past, local officials had siphoned off tax revenue before it reached Istanbul.7 Specifically, abuses in the tax-leasing system had to be removed from the revenue assessment and collection process.

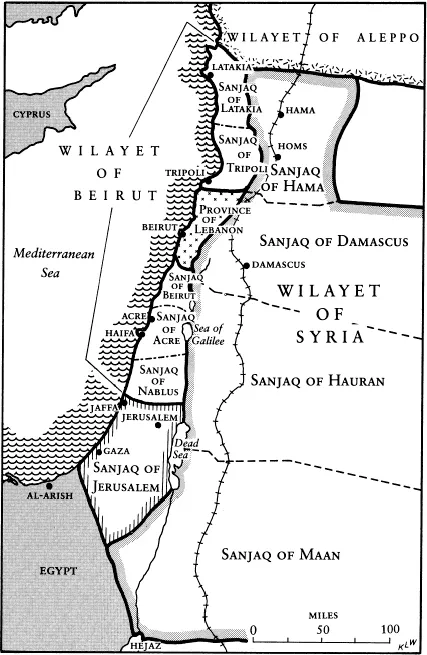

Prior to the promulgation of the Hatti Sherif of Gulhane in November 1839, which outlawed tax farming, the long-term office of the wali, or regional administrator, permitted the incumbent virtually unchecked accumulation of power and wealth through tax collection. However, in the rural areas of Palestine, particularly in the hill regions, shaykhs, who were village or tribal chiefs and influential heads of families, continued to control local administration. This local elite exercised control in a feudal and somewhat despotic manner. In the Carmel mountain range near present-day Haifa and in the environs of Jenin and Nablus, individuals and particular families had achieved local jurisdiction over particular villages or land areas through economic and political dominance. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, families locally prominent particularly in the sanjaqs, or districts, of Nablus and Acre, solidified their accumulated local authority by serving in bureaucratic positions of municipal and regional administrations.8 The administrative units of Ottoman Palestine are shown in Table 3.

The leadership of the Palestine Arab community during the early years of the Mandate came from this landed elite or were tied directly to them through familial and social bonds of mutual self-interest. A close review of administrative positions previously held under the Ottoman regime for the sanjaqs of Acre and Nablus indicates continuity of these families in politics during the first fourteen years of the Mandate. From the nine subdistricts including Acre, Haifa, Tiberias, Beisan, Safed, Nazareth, Jenin, Tulkarm, and Nablus, forty-one different individuals were elected regional representatives to the Arab Executive at the Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Palestinian congresses. Of these, twenty-six representatives either had served in Ottoman qaza (local jurisdictions), were sanjaq administrators, or were immediate relations to these administrators.9

TABLE 3 Administrative Units in Palestine Prior to World War I

Regional Wilayet (Wali) | Administrative Units District Sanjaq (Mutsarrif) | Local Qaza (Qaimmaqam) |

Beirut, Jerusalem | Acre, Nablus, Jerusalem | Acre, Haifa, Nazareth, Safed, Tiberias, Jenin, Nablus, Tulkarm, Beersheba, Gaza, Hebron, Jaffa, Jerusalem |

Source: Royal Institute of International Affairs, Great Britain and Palestine, 1915–1945: Information Paper no. 20, p. 178.

In order to counter the autonomy of regional officials and rural tax collectors, the Wilayet Law of 1864 redefined the role of the local administrative councils. But instead of eradicating abuses in tax collection, the duties and composition of the established majlis idara, or district administrative councils, merely perpetuated them. To participate in these local councils a candidate had to pay a yearly direct tax of at least 500 piastres. This restriction limited participation to those who had previously owned or worked land and who were not fearful of contact with the central government. The Ottoman Electoral Law of 1876 solidified political control in the hands of taxpayers and particularly those who sat on the majlis idara. As a result of the tax qualification, the majority of the rural population had no voice in the management of their own affairs in Palestine during the late Ottoman period.10

By the Wilayet Law of 1864, the majlis idara was vested with local authority over land and land taxation. With the institution of the Ottoman Land Code of 1858 and subsequent registration of land, members of the local majlis idara authorized the assessment and collection of taxes, approved land registration, decided questions of landownership, and expressed influential opinions about the ultimate fate of lands that reverted to the state. Each local majlis idara was to have a mufti and a qadi (Muslim religious and judicial officials) in addition to the four government-appointed officials, four nongovernment-elected officials, and four representatives of the non-Muslim religious communities. But, in fact, the non-Muslim communities were underrepresented while Muslim religious leaders and landowners were represented in much greater proportion to their population, thus reinforcing their political position and furthering their private interests.11

2. Syria and Palestine, 1915

In addition to the majlis idara, there were other commissions, boards, councils, and committees at the qaza level which gave their members considerable prestige and access to control of local politics through land accumulation. Membership of governmental units at the qaza level at least in 1893, 1900, and 1908 suggests that certain local families dominated varying facets of local administrative activity. In the sanjaqs of Acre and Nablus the local administrative elites tended to remain constant. The administrative offices included positions for civil servants on the municipal councils...