![]()

CHAPTER ONE

In the Public Eye

In the first half of the twentieth century, college students seemed to be everywhere. Their football games were followed at a national level, their dances were deemed immoral, and their hygiene habits were suspect. Journalists, social commentators, and educators dissected nearly every aspect of collegians’ culture, and did so in front of a very interested American public. Songs such as 1925’s “Collegiate” proclaimed the undergrad’s arrival: “Trousers baggy. And our clothes look raggy. But we’re rough and ready.”1 They were rough and ready—to play and to buy.

Collegians came to national attention in the 1910s, phased into a raccoon-coated phenomenon in the 1920s, and proved their collective buying power in the 1930s. Itself just a newcomer to the country’s cultural landscape, the American fashion industry understood that “casual clothing which will stand up under hard wear and still continue to look well is what the co-ed wants.”2 Yet retailers, manufacturers, and fashion editors struggled to understand and meet the group’s demands. Princeton was inundated with trend scouts who were looking for inspiration. In 1936, a student reporter snipped, “It’s hardly worth an undergraduate’s life these days to appear on the campus in presentable garb. If he does, a dapper gentleman with a camera pops out from behind some tree or other, snaps a quick photo, and the next thing the bewildered undergrad knows, he finds himself in the style magazines or in clothing advertisements.”3

Retailers recruited students to help select and sell back-to-school styles. Magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post (1897), Vanity Fair (1913), Esquire (1932), and Mademoiselle (1935) ran advertisements, fiction, and fashion advice aimed to catch the eye of collegians—or the many others who followed their cultural lead. “College students,” writes historian Paula Fass, “were fashion and fad pacesetters whose behavior, interest, and amusements caught the national imagination and were emulated by other youth.” This power “turned the idea of youth into an eminently salable commodity.”4 In 1932, fashion theorist J. C. Flugel noted the influence of college youth on their parents’ generation: “Maturity has willingly forgone its former dignities in return for the right of sharing in the appearance and activities of youth.”5 Illustrations by John Held and novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald delivered a deceptively homogenous collegiate experience in which everyone was white and upper middle class.

Visible cracks came to the surface after World War II, as the sheer number of collegians made even the semblance of monolithic student culture impossible. The ranks of college students swelled from 1.5 million in 1940 to 3.7 million in 1960.6 These new recruits came from across the socioeconomic spectrum, but the bulk of them were solidly middle class. With time, students became increasingly disenchanted with the status quo. Historian of student culture Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz writes of the 1960s, “Traditional college life had lost its appeal to many. Schools suspended college rituals due to lack of interest.” Clothing made to “distinguish between the sexes, and enhance status, gave way to revealing, ‘natural,’ androgenized looks democratized by denim.”7 A more diverse collegiate demographic and an increasingly powerful teenage market complicated the fashion industry’s attempts to understand youth’s tastes. In many ways, as historian Thomas Frank has explained, “The conceptual position of youthfulness became as great an element of the marketing picture as youth itself.”8 In 1969, the editor of Mademoiselle told fashion industry insiders, “For the first time in history, there is freedom of fashion choice . . . the mature and the young can establish her own identity, express her own individuality, and, as never before, do her own thing.”9 “Lifestyle,” with its celebration of personal choice, guided consumption. As fashion executives, publicity agents, and department store buyers learned, one size no longer fit all.

What and how an individual student bought depended on circumstance, individual tastes, and most significantly, personal finance. Radcliffe freshman and clotheshorse Nancy Murray (Class of 1946) wrote of her relationship with spending: “Money is liquid and flows gaily in the wrong direction—to other pockets than my own.”10 Princeton’s Chalmers Alexander (Class of 1932) received weekly boxes of his maid’s oatmeal-raisin cookies and his mother’s latest offerings for his wardrobe. His purchasing instructions were exacting, and many packages were exchanged between his home in Jackson, Mississippi, and his dorm room in New Jersey. Despite his seemingly affluent background, the tightly wound Chalmers methodically documented daily expenses. During the Depression, the family’s financial situation was dire, and Chalmers moved to Edwards Hall, a dorm he described as “old and shaggy and the lowest ranking dormitory on campus (a lot of boys who are working their way through).” The move was difficult, and he admitted to his parents, “I naturally would prefer not moving there just as you’d prefer not moving to South Jackson.”11 The decision to buy or not to buy was ultimately a personal one.12

“A Kind of ‘Exhibit X’”: Collegians Come to the Fore

The number of college-going youth grew from nearly 240,000 in 1900 to 600,000 in 1920—a 150 percent increase that repositioned collegians on America’s cultural landscape.13 Ready-to-wear clothing manufacturers and retailers realized that collegians’ dress standards were markedly different from those of their parents. College men sought clothing that proclaimed their alliance to the campus’s all-important sports culture. These men wanted comfortable, practical clothing that could be worn from the golf course to the dining hall to the classroom with few social repercussions. Magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s brought images of J. C. Leyendecker’s Arrow Collar Man and tales of gridiron battles into American homes and lives. Manufacturers such as Brooks Brothers stepped in to supply the demand. For college women, however, this distinctly new genre of dress called “sportswear” met with raised eyebrows from social critics. While college women were identified as potential consumers, the retailers, manufacturers, and magazine editors of the 1910s were slow to pursue them.

In the first years of the twentieth century, a cultural interest in youthfulness brought collegians to the attention of the American public as never before. Historian Bill Osgerby argues that the growing emphasis on age stratification was a result of changing demographics and labor markets interfacing with “developments in the fields of legislation, family organization and education to mark out young people as a distinct group associated with particular social needs and cultural characteristics.”14 In the early decades, a new masculinity emerged that stood “in stark contrast to Victorian ideals of masculinity that had prized diligence, thrift and self control.” As witnessed in the educational writings of G. Stanley Hall, the Rough Rider rhetoric of Theodore Roosevelt, and the naturalist novels of Frank Norris, the male “body itself became a vital component of manhood: strength, appearance,” writes historian E. Anthony Rotundo, and “athletic skill mattered more than in previous centuries.”15 The emphasis on youth’s physical wellness was, in the words of one Princeton educator, about “more than health and strength.” Joseph E. Raycroft, the head of the university’s Hygiene and Physical Education Department, told alumni in 1915 that by staying fit, the American man was “getting a training in emotional control and an ability to adapt himself successfully to changing conditions that give poise and confidence.” These experiences, said Raycroft, were “the most effective ways of educating and developing the real man that lies back of his intellectual processes.”16 Well-funded institutions had elaborate facilities. The lore of Yale’s gym, swimming pool, and locker rooms made it all the way to the West Coast. A Cal student who had visited New Haven in 1912 reported in his student newspaper of the private fencing, boxing, and wrestling lessons available.17 Morehouse College was on the other end of the spectrum, and its students raised money for their own gym. At Morehouse, sports were “encouraged under restrictions that prevent danger to health and neglect to regular school duties.”18 Administrators kept a close eye on the men’s exercise to ensure it aided in the “development of manly qualities and moral character.”19 Historian Martin Summers writes of the growing tension between school administrators and young black men on the campuses of Fisk and Howard. The students were “rebelling against the imposition of late-Victorian standards of morality at a time when the ascendancy of consumer culture was increasingly undermining the importance of producer values and respectability among the American middle class.” “At stake,” says Summers “was the [men’s] desire and ability to control their own bodies, the freedom to consume and experience bodily pleasure without fear of being punished.”20

Figure 1.1. An avid shopper even during wartime, Nancy Murray (Radcliffe, Class of 1946) wrote to her parents in September of 1942, “Money is liquid and flows gaily in the wrong direction—to other pockets than my own.” Here, she wears saddle shoes, a man’s work shirt, and dungaree jeans (note the heavy seams and patch pockets). This kind of clothing was first worn in the 1930s on elite women’s campuses in the Northeast but became standard campus wear for women during World War II. Murray’s letters home chronicled her buying and beautifying regimen. She wrote of a new and costly perm, a lost earring, and a cocktail dress that was too long. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

As social critics, educators, and the students themselves reconceptualized the American man as youthful and healthful, J. C. Leyendecker gave him an enduring image in the Arrow Collar Man.21 In the first decades of the century, Leyendecker produced illustrations for fashion companies such as Kuppenheimer and Hart, Schaffner & Marx, but his work for Arrow Collars, based in Troy, New York, proved most popular. Arrow Collars and college men were silent partners in the transition from the hard, detachable collar to the more casual, soft or rolled collar. The soft collar was first worn at Princeton around 1912 and then picked up on other campuses after World War I. Students, recent graduates, and the many others who followed collegiate fashions saw themselves in Leyendecker’s creation. For example, the Penn State student in figure 1.2 sports a clean-shaven face, lightly slicked (or “watered” hair), and the all-important letterman’s sweater. The Arrow Collar Man’s fresh-faced appeal broke with “previous notions of masculinity that relegated grooming and fashion to the feminine sphere.”22

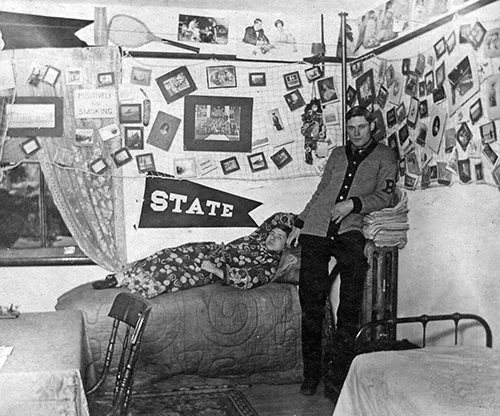

Figure 1.2. The fresh-faced, athletic college man became a cultural icon in the first decades of the twentieth century. His letterman’s sweater was a badge of allegiance to the campus sports culture, making it a sought-after fashion statement. Sweaters—and their less formal cousins, sweatshirts—became staples of casual style because they inspired versatility. This 1908 Penn State student and his roomate lounging on the bed behind him demonstrate the varieties of dormwear. Thick robes and wool sweaters were practical solutions to drafty dorms. Courtesy of the Penn State University Archives, Pennsylvania State University Libraries.

In the first decade of the century, magazines such as Scribner’s, Collier’s, and Good Housekeeping featured articles about white college students, but not necessarily for them. The magazines’ readers were middle-class Americans, those who aspired to (and did) send their children to college. Hence, hopeful and prospective parents were the target audience. Many insiders believed the result of this coverage to be a “superficial glance,” as one put it, made by “theoretical critics who have never lived on a college campus, but have gained their information in secondhand fashion from questionnaires or from newspaper-accounts of the youthful escapades of students.” Such a portrait painted the collegian as “an enigma . . . not exactly a boy, certainly not a man, an interesting species, a kind of ‘Exhibit X.’”23 Magazines were routinely charged with miscasting collegians as pranksters or dilettantes. By the eve of World War I, publications such as the Saturday Evening Post and the more heady Smart Set, whose tagline was “A Magazine of Cleverness,” had established a readership of actual undergraduates. Vanity Fair was the most coveted magazine by the clothing-conscious collegian. Only one year after it was launched in 1914, the Condé Nast publication ran more pages of advertisements than any other magazine. College students were front and center in the magazine’s target dem...