![]()

PART I

A Community Historian

Exploring Queer San Francisco

![]()

CHAPTER 1 Lesbian Masquerade

Originally published in Gay Community News, November 17, 1979, 8–9.

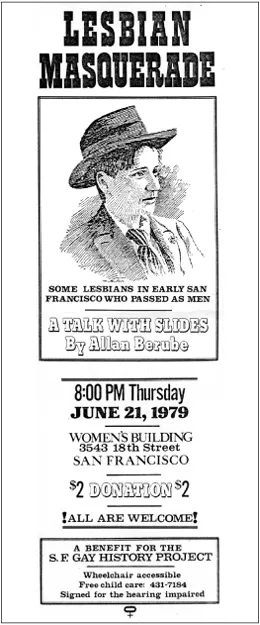

This essay is a revised version of an illustrated lecture that Bérubé first presented in San Francisco in June 1979. Inspired by the section in Jonathan Ned Katz’s Gay American History (1976) titled “Passing Women”—which revealed a long tradition of women who dressed, lived, and worked as men—Bérubé searched through San Francisco newspapers for local evidence of the phenomenon. He places his stories in the context of the newly emerging field of U.S. women’s history and sets them as well in the local setting of San Francisco. Although very much constructed as a discovery of hidden lesbian lives, the showings of “Lesbian Masquerade” also inspired some of the first explorations of transgender history. The essay was originally published in Gay Community News, a Boston-based politically progressive newspaper with a national circulation. Like much of the community press in the post-Stonewall era, it not only reported news but served as an outlet for early writing in gay and lesbian history.

In the last few years lesbian and gay historians have begun piecing together a history of the varied experiences of lesbians in America. They have discovered, for example, large collections of love letters between middle-class women who attended nineteenth-century women’s colleges or who were active in the early feminist, labor, and settlement house movements. They have also found evidence of lesbian relationships among women who worked in nineteenth-century factories and department stores and who lived in residence and boardinghouses.

Perhaps the most visible lesbians of nineteenth-century America were women who passed as men and married other women. American newspaper headlines such as “Poses, Undetected, 60 Years as a Man,” “A Gay Deceiver of the Feminine Gender,” and “Death Proves ‘Married Man’ a Woman” announced the shocked discoveries of these women’s deceptions. These reports appear to become more frequent beginning in the mid-1800s and represent, I suspect, only the tip of an iceberg. They are possibly the most visible

evidence of a larger social phenomenon in which many American women chose to abandon their feminine roles and successfully pass as men.

Flyer for Bérubé’s first slide lecture, with an image of “Babe Bean” (Elvira Virginia Mugarietta), one of the women who passed as men featured in the talk. Courtesy of the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project Papers at the GLBTHS, San Francisco.

A brief historical background might help explain why these women chose to pass as men in mid-nineteenth-century America. Before the nineteenth century, most Americans lived in villages or on farms where work, while thought of as women’s work or men’s work, was integrated with home life. In this young country everyone’s labor was valuable, and women were known to work as innkeepers, farmers, shopkeepers, and merchants in villages and towns.

As cities grew and industrial capitalism expanded, men left their households to enter a world of paid labor from which women were excluded: a world of business, politics, and civil service where men socialized with each other in taverns, beer halls, and saloons. Women found few opportunities in this all-male world and were hired only as the lowest-paid workers in factories, a place reserved mostly for immigrant women. While men worked for wages outside the home, the work inside the home—housework, rearing children, providing for the family’s domestic needs—became the unpaid work of women.

At the same time that men were separating their world from women’s, the differences between the sexes were artificially exaggerated so that, according to historian Mary Ryan, “by 1860 sex had cut a bold gash across all of society and culture, bluntly dividing American life and character into two inviolable spheres labelled male and female.” Not only was the home feminized and the workplace masculinized, but extreme masculine and feminine values were assigned to articles of clothing, emotions, language, skills, and mannerisms.

Many women began measuring their lives against a new ideal of womanhood based on this exaggerated femininity. The ideal middle-class woman in mid-nineteenth-century America did not work for wages; instead, she was supported by her husband or father. She was supposed to be maternal and sentimental and remain at home taking care of her children. Seldom in the company of men, she lived in a nearly all-female world. She didn’t drink, smoke, swear, or travel alone. She was soft spoken, wore corsets and petticoats—never shirts or pants—and bore the responsibility of keeping the men in her life properly moral and religious. She was assumed to be sexually passive and pure and did not discuss sexual matters, which belonged only in the world of men.

Not all women, of course, lived according to this middle-class ideal of womanhood. Most black women and men, for example, labored under the same oppressive system of slavery, a system that treated both men and women as property. Immigrant and working-class women did work for wages, but these wages were so low that it was nearly impossible for a working woman to support herself. Middle-class women who were unmarried had few options and faced poverty and social disapproval as “spinsters” and “old maids.”

Women in mid-nineteenth-century America began to find it increasingly difficult to escape these economic and social restrictions. Some women resisted these restrictions on their lives in imaginative and often extreme ways. Married women, for example, sometimes formed passionate and devoted relationships with other married women that lasted for decades. Other women entered the all-male public world and, despite public scorn, began movements for abolition of slavery, labor unions, moral reform, birth control, and women’s suffrage.

Still other women entered the privileged world of men by successfully “passing” as men. For many women, passing as a man was one way to live an economically independent life. “I made up my mind,” wrote Lucy Ann Lobdell in 1855, “to dress in men’s attire to seek labor, as I was used to men’s work. And as I might work harder at housework, and only get a dollar per week, and I was capable of doing men’s work, and getting men’s wages, I resolved to try to get work away among strangers.” Lucy Ann Lobdell lived with a woman as “husband” and “wife” for over a decade. A woman named Charles Warner recalled that in the 1860s, “when I was about 20 I decided that I was almost at the end of my rope. I had no money and a woman’s wages were not enough to keep me alive. I looked around and saw men getting more money and more work, and more money for the same kind of work. I decided to become a man. It was simple. I just put on men’s clothing and applied for a man’s job. I got it and got good money for those times, so I stuck to it.” Charles Warner passed as a man in Saratoga Springs, New York, for over sixty years.

A woman who passed not only earned more money for the same work; she could also open a bank account and write checks, own a house and property, travel alone, even vote in local and national elections. In 1876, for example, a woman living as Albert B. Clifton told a Long Island judge that she “prefers men’s clothing because she can see more and learn more as a man than as a woman.” And Murray Hall, who passed for over twenty-five years and twice married women, became a prominent New York politician in the 1880s and 1890s and voted for years in both primary and general elections.

How did these women successfully pass as men? In addition to wearing men’s clothes, often borrowed from a brother or cousin, these women had to perfect men’s language and tone of voice, as well as gestures, walk, and habits, including smoking and drinking. They had to be physically strong, confident on the street, and be able to flirt with women. For some women, this behavior came naturally. Others, like “Mr. L. Z.,” a lesbian in Boston, “took great pains to observe carefully the ways of masculinity in general and even has taken lessons in manly deportment from an actor under the pretext of turning to the stage.” Descriptions of these women included much more than clothing. “She drank,” went a typical account, “she swore, she courted girls, she worked as hard as her fellows, she fished and camped, she even chewed tobacco.”

Passing involved great risks, especially discovery, which meant a loss of freedom and independence, and could create a scandal and bring on arrest or even a court order to wear women’s clothes. Some women risked their lives rather than be discovered. Murray Hall suffered from breast cancer for years, and only when she was near death did she risk seeing a doctor, who neither cured her nor kept her secret. Physicians were most to be feared. Many of the passing women we know about today were exposed to the press by doctors in hospitals, prisons, and the military.

Many passing women, but not all, courted, lived with, or married other women. Mid-nineteenth-century reports sometimes explained these marriages as expressions of women’s rights. An 1867 San Francisco newspaper story, for example, about Mary Walker, a passing woman from Richmond, Virginia, and her female fiancée noted that “they are not to be married at present, as women’s rights have not attained to that degree of development.” We may not know for sure if all of these relationships were sexual, but it is important to affirm that these women were capable of fulfilling each other sexually, even if they had to keep their sexuality a secret.

Women who passed as men not only gained economic independence; they also could become sexually assertive and attractive to other women without raising eyebrows. This was an unusual experience for many nineteenth-century women, who were raised to be sexually passive. All passing women had to decide how they would relate to other women. These relationships ranged from bachelorhood to publicly marrying another woman and living as husband and wife. Some women may have passed in order to justify their sexual love for women. Others may have passed as husbands to gain social acceptance for a love that would otherwise have been condemned. For still other women, passing may have come first, providing a woman with a series of experiences, such as being able to live independent of men, that allowed two women to live together in a lesbian relationship without a man’s support. In any case, the connections between passing and sexuality are complex, and the motives of passing women need to be explored further.

In 1854, thirty-five-year-old Lydia Ann Puyfer was arrested in New York City for wearing men’s clothes. When asked why she was thus attired, she explained to the judge that she was “from Gowanus, Long Island, that she had stolen her cousin’s clothing with the intention of shipping as a seaman, and that she was bound for California.”

Lydia Ann Puyfer was not alone on her journey to California. From the days of the 1849 Gold Rush, San Francisco’s reputation as a wild and pleasure-loving city that tolerated all types of “eccentrics” attracted people considered social misfits “back East.” Its reputation as a “gay mecca” is not a sudden product of the 1970s but has roots that go far back into the nineteenth century.

While accounts of lesbians who passed as men appeared in nineteenth-century newspapers from all over the United States, an examination of the accounts from a single city such as San Francisco can ground these women’s lives in local history. From a preliminary search through scrapbooks of early San Francisco newspaper clippings for lesbian- and gay-related materials, I have found many detailed accounts of lesbians who passed as men. I suspect that a search through newspapers of most American cities, together with oral histories of older lesbians, would uncover similar stories. The San Francisco accounts are already beginning to reveal a lost local tradition of passing women, many of whom were well known during their lifetimes in San Francisco and throughout California.

Jeanne Bonnet, for example, grew up in San Francisco as a tomboy and in the 1870s, in her early twenties, was arrested dozens of times for wearing male attire. She visited local brothels as a male customer and eventually organized French prostitutes in San Francisco into an all-woman gang whose members swore off prostitution, had nothing to do with men, and supported themselves by shoplifting. She traveled with a special friend, Blanche Buneau, whom the newspapers described as “strangely and powerfully attached” to Jeanne. Her success at separating prostitutes from their pimps led to her murder in 1876.

Another San Francisco woman, “Babe” Bean, passed for forty years as a male Red Cross nurse, soldier, and charity worker. She was discovered in 1897 when she briefly became a reporter for a Stockton, California, daily newspaper, where she described her experiences passing in hobo camps, prisons, gambling halls, and saloons, and on the city streets.

The following narrative of Luisa Matson’s life in San Francisco from 1895 to 1907 is one kind of detailed account of a lesbian passing as a man that can be compiled from local newspaper articles. The reporters who wrote these articles, of course, expressed a male bias that saw passing women as “imitation men” and ignored these women’s “wives” and lovers. This bias distorts nearly every nineteenth-century account of passing women and reflects an attitude that the “masqueraders” were curiosities, while their lovers were ordinary women. In the following story of Luisa Matson’s life I have included as much about her lover, Helen Fairweather, as the newspapers revealed.

A SECRET FOR YEARS

LUISA WATSON MASQUERADED AS A MAN

Her Sex Revealed in Jail

Once Engaged to a Young Lady

In late January 1895, police arrested Milton B. Matson in Los Gatos, California, twenty-five miles south of San Francisco, for passing bad checks. Matson had been running a summer resort in nearby Ben Lomond and had run up a series of debts which he was unable to pay. Police booked him at the county jail in San Jose and threw him into the tank with “the rabble and tramps and petty larcenists.” Four days later police hurriedly removed Matson from the all-male cell and took him upstairs to the sheriff’s private office for questioning.

The district attorney had discovered that Matson had received bank orders made out to Luisa Elisabeth Blaxland Matson. When asked who this woman was, Matson replied, “My half sister.”

“‘Matson,’ the D.A. said impassively, ‘those orders are either forged or you and Luisa Elizabeth Blaxland Matson are one and the same person, and you are a female.’

“‘Then the question is easily solved,’ exclaimed Matson, ‘for I am a male.’”

The officers were not convinced, however, and before long Milton B. Matson admitted that she was a woman. “She seemed very much embarrassed that her deception had been discovered. She tried hard to make the officers promise not to disclose her secret to anyone. She was particularly anxious that the story be kept from the prisoners.” Reporters, of course, were close at hand, and Luisa Matson’s story began to unfold.

Forty-year-old Luisa Matson had passed as a man all her adult life, supporting herself by working in the hotel and real estate business in Australia and California. She supplemented her income with small monthly remittances from her disapproving family in England. “In my early youth,” she explained, “I was sort of a nondescript. I was fond of outdoor sports, and before I was 17 years of age I was attired in garments about half-masculine. When I became two or four or six and twenty, somewhere around there, I put on the entire male garb. I did not find it at all inconvenient; in fact, it seemed natural to me from the first.”

The next day a full interview with Matson appeared in the San Francisco Call, beginning with the following curious headline:

LOS GATOS FOLKS SAY SHE WAS GAY

BUT THE PRISONER SAYS SHE HAS BEEN

STRAIGHT ALL HER LIFE

A DENIAL OF HER LOVE AFFAIR

The word “straight,” incidentally, was not used on the West Coast to mean “heterosexual” until the mid-twentieth century. In this headline, “gay” probably meant “living a wild life,” and “straight” may have meant “moral and law-abiding.” Yet it is curious that these words were used as opposites in 1895, especially in reference to a love affair between two women.

Upon entering the sheriff’s office for the interview, Matson “was seated at a desk which [had] been provided for her.” Her light-colored trousers were turned up at the bottom in true English style. A black cutaway coat and eyeglasses contributed to make a very natty appearance. As the reporter and artist entered, she rose to the full majesty of her five feet and seven inches and gazed sternly at the intruders.

“‘It seems outrageous,’ she declared, ‘t...