![]()

1

Intermediate Andean Cities

Riobamba and Cuenca are two in a chain of intermediate cities (not including the capital Quito) in the Ecuadorian highlands, which are in the Andes. This mountain chain extends from the border with Colombia in the north to the one with Peru in the south. Riobamba is in the central part of Ecuador, south of Quito, about a four-hour bus ride from the capital. The city is situated at an altitude of 2,750 meters (9,022 feet), on a plateau surrounded by various mountains and volcanoes. The air is thin, the sunshine brighter than in the valleys, the nights are cold, and when the wind picks up, the gusts are very strong. Riobamba is popularly known as La Sultana de los Andes, a name of unclear origin that the inhabitants and the municipal authorities use to express the serene, stately bearing of their city. Only the center of Riobamba is crowded during the day. Vendors and people visiting the market, including many Quechua, flock to the local markets, where regional products are purchased and sold. Because Riobamba is the urban center of an agrarian region, the pace is adapted to rural life. In the daytime the city center is lively and colorful, but in the evening it appears deserted. Restaurants close at the end of the afternoon, as the almuerzo (lunch) is the main meal for Ecuadorians. Riobamba is a city with the ambience of a village.

Cuenca is different. This city is about seven hours south of Riobamba by bus and is situated at an altitude of 2,500 meters (8,202 feet). Cuenca is in a valley, surrounded by hills and bisected by four rivers. Rather than having a harsh highland climate and being surrounded by high mountain peaks, Cuenca lies in a green, hilly setting and has a mild climate. The city is a popular tourist venue, thanks to its well-preserved monumental edifices in the center. Cuenca does not seem larger, although it is more cosmopolitan and wealthier than Riobamba. Its inclusion on UNESCO's world heritage list and improved accessibility have boosted international tourism. Airplane travel has recently become an alternative to the lengthy bus rides. Planes now fly daily from and to Quito and Guayaquil, making the journey to Cuenca in less than an hour. Cuenca, which is a service center rather than a market town, is populated by office workers during the day. In the evenings, tourists and locals enjoy the many restaurants and cafes in the city center. Contrary to Riobambans, who often apologized to me for the circumstances in the city, most Cuencans take pride in their city, as conveyed by its nickname Atenas del Ecuador—a bold reference to the valuable historic architecture in the city center and to the artists and intellectuals who abound in the city. The nickname corresponds with the image exuded by the elite, who depict Cuenca as a civilized and culturally sophisticated society and believe that its cultural refinement give it a European ambience.

In this chapter I will describe a few characteristics of intermediate cities in the Ecuadorian Andes in general and of Riobamba and Cuenca in particular. First, I will review the administrative, legal, and historical context of cities in the highlands. Next I will describe Riobamba and Cuenca in more detail. In the paragraph about urban development, I consider current trends arising from globalization. I also describe international influences, for example that of tourism on ideas about the desired cityscape and the built environment. My description of historical and current trends provides the context in which professionals and residents of working-class neighborhoods operate. Afterwards I address local working-class housing, as a framework for the circumstances of working-class residents. I explain how national public programs for social housing construction are implemented locally. Since even working-class housing policy is implemented by individuals, I conclude the chapter with an impression of the views of the municipal authorities on working-class neighborhoods. The programmatic image, together with the impressionist view of Cuenca and Riobamba, are an introduction to the empirical chapters that follow.

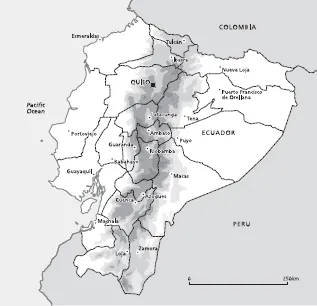

Map 1. Ecuador*. Graphic design and cartography by Rien Rabbers and Margot Stoete (Geomedia, Utrecht University); © Christien Klaufus.

*The Galapagos islands are not included in these data.

Table 1. Ranking by population of cities in Ecuador, 1950

| Rank | City | Population 1950 |

| 1 | Guayaquil | 258,966 |

| 2 | Quito | 209,932 |

| 3 | Cuenca | 39,983 |

| 4 | Ambato | 31,312 |

| 5 | Riobamba | 29,830 |

| 6 | Manta | 19,028 |

| 7 | Portoviejo | 16,330 |

| 8 | Loja | 15,399 |

| 9 | Ibarra | 14,031 |

| 10 | Milagro | 13,736 |

Source: CEPAL (2001)

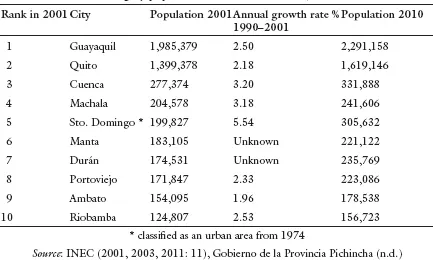

Table 2. Ranking by population of cities in Ecuador, 2001 and 2010

Cities in the Ecuadorian Highlands

Urbanization in Ecuador

Ecuador comprises twenty-two provinces, which are administered by consejos provinciales. Each province is subdivided into territorial units called cantones. These cantones are known in political and administrative terms as municipios. Municipios are subdivided into urban parroquias, which together constitute the urban area or the city (even if their size, morphology, or ambience may not seem “urban”), and rural parroquias outside the city limits (INEC 2002). Municipalities are run by councils, comprising a mayor and aldermen. Officially they are in charge not only of their city but of the surrounding rural parishes as well, where they work with the juntas parroquiales (village councils). The parishes inside the city limits, however, have no administrative status (Bolay et al. 2004: 63). Organizations of city dwellers tend to be district rather than parish-based, and most districts belong to the local Federación de Barrios that exists in each city. Ideally, the Federación de Barrios helps plan and implement district and neighborhood projects. The actual practice is often different, as I will explain in the chapters ahead.

Ecuador's present urban constellation goes back a long way. During the colonial period, the Andes mountains were pivotal in the Real Audiencia de Quito. The small and medium-sized towns in the resulting chain were the country's most important urban centers until the end of the nineteenth century (see Map 1). The rural areas in the highlands were run from the cities that the Spaniards established, usually on pre-Incan settlements. The highlands, with their temperate climate, became the national center of agricultural and textile production. With the increase in exports of cacao, which was grown on plantations along the coast, the coastal region became dominant from 1880 onward. In the early twentieth century migration began from the highlands to the coastal region, where sufficient employment opportunities were available on the plantations (F. Carrión 1986). The coastal cities expanded rapidly.

Around the mid-twentieth century, the country experienced an economic recession related to the worldwide recession arising from the First and Second World Wars, the decline in cacao exports, and the deterioration of the agricultural system of large landownership (F. Carrión 1986). In the 1950s and 60s these developments gave rise to a policy based on import substitution. Revenues from banana and oil exports were invested in local industries. As a consequence, demand increased in the large cities and in lesser measure in the provincial cities for factory workers, and migration flows got under way from the rural areas to the cities.

The agricultural reforms in the 1960s and '70s influenced this migration as well. Pressured by the United States, a military junta that had come to power in 1963 introduced two reform acts. These measures reflected the American Alliance for Progress agenda intended to eliminate the communist threat in Latin America. The agricultural reforms served to alleviate social unrest and modernize production in the countryside. In addition to agricultural reforms, which were coordinated nationally by the Instituto Ecuatoriano de Reforma Agraria y Colonización (IERAC) (Navas 1998), the program comprised various measures to promote construction of inexpensive housing (Pike 1977: 303–38; Handelman 1981: 70; Garcia 1987: 104; Glasser 1988: 150; Ward 1993: 1144). The land reforms were not a great success, due to opposition from powerful and well-organized large landowners. The output from the resulting minifundios was often insufficient for basic subsistence. Inheritance led the small plots of land to become still more fragmented and increased the pressure to grow the output. Rural poverty deepened, especially because the government kept incomes in the agricultural sector artificially low to curtail the cost of living of the expanding urban population. This boosted seasonal and permanent migration from the countryside to the cities (Handelman 1981: 63–81; Schodt 1987: 122; Corkill and Cubitt 1988: 33–37).

Urbanization in Ecuador is relatively recent (see Table 1). Until well into the 1980s, the majority of the population lived in the countryside, and in 1990 this share remained 45 percent (CEPAL 2001). Only over the past two decades has urbanization truly advanced and are urban growth indices high, especially in intermediate cities (see Table 2). In the second half of the twentieth century the port city Guayaquil and the capital Quito ranked at the top in terms of population. Between 1950 and 2001 the population of Guayaquil grew from over 250,000 to nearly two million inhabitants, while the population of Quito increased from over 200,000 to more than a million during this same period (see Tables 1 and 2). Guayaquil and Quito are now home to over one third of Ecuador's population. Uncontrolled expansion of these cities has given rise to unplanned residential areas, where rural migrants settled without basic facilities or property deeds. These areas, where living conditions were far from ideal, arose spontaneously or informally.

During the second half of the twentieth century smaller cities also experienced an influx of migrants, who settled along the periphery. Around Cuenca and Riobamba, dozens of working-class neighborhoods arose following the sale—in some cases illegal—of the territory from former haciendas. Those purchasing the tracts of land were largely uneducated migrants from surrounding villages and other parts of the country. Many of these buyers believed that they had bought the land legally. They would build their home there without an official permit, hoping that the district, together with the buildings, would soon acquire official authorization. Since the status of land and homes in working-class neighborhoods is highly complex and not necessarily illegal (I will elaborate on this in later chapters), I refer to them as informal districts. Some residents have improved their living conditions over time, despite minimal government support. Residents of working-class neighborhoods in the provincial towns in this study in fact represent a socioeconomically diverse group and are not always in need of assistance. Designations such as slums or villas miserias do not in my view do justice to the somewhat modest but still respectable abodes that my respondents built or are still building. I prefer the term working-class neighborhood, which is hopefully less pejorative.

In recent decades one important difference has materialized between the intermediate cities in the coastal region and those in the highlands. The coastal cities have experienced a massive influx of new residents, and the annual population growth of cities such as Santo Domingo and Machala exceeds that of Guayaquil and Quito (CEPAL 2001; Ortiz 2003: 253). In the national urbanization pattern, Riobamba and Cuenca are generally regarded as experiencing steady, controlled growth. The figures also show, however, that even cities experiencing a drop in ranking, such as Riobamba, expanded over the course of a few decades from centers with a few tens of thousands of inhabitants to areas with over 100,000 people. A relatively steady increase in population therefore does not mean that this growth is negligible. Informal neighborhoods in cities without explosive growth are rarely designated by the national government and by development aid organizations as target areas. The emergence of new, affordable housing developments therefore depends primarily on the efforts of local authorities, professionals, and especially current and prospective neighborhood residents.

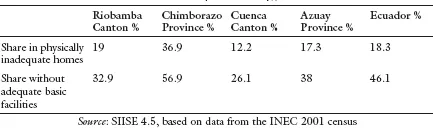

Table 3. Inadequate housing, 2001

The housing shortage in Cuenca and Riobamba is not cause for serious concern, given the figures for the country as a whole (see Table 3). According to the SIISE figures, which are based on the census from 2001, about one-fifth of the population in the Riobamba Canton (comprising the city and a few surrounding rural communities) lived in housing that could be described as physically inadequate, for example due to the inferior construction materials. Nearly one-third of the population lacked basic facilities, such as running water and electricity. Living conditions were worse in the rest of the province. The housing shortage in the Riobamba Canton equalled the average for Ecuador as a whole. Cuenca is regarded as a city where urban planning and housing policy are properly institutionalized by Ecuadorian standards, as apparent from the figures (Lowder 1990). In the Cuenca Canton 12 percent of the population lived in inadequate housing, and over a quarter lacked access to basic facilities. Cuenca scored better than the average for the Azuay Province in this respect and was well above the national average as well. Riobamba and Cuenca therefore do not seem like bad places to live.

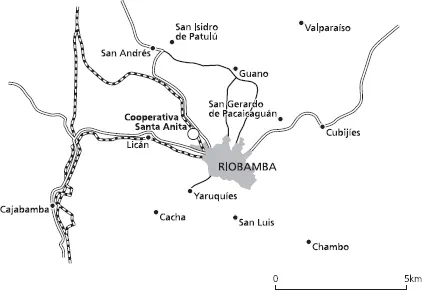

Map 2. Riobamba and surrounding areas. Graphic design and cartography by Rien Rabbers and Margot Stoete (Geomedia, Utrecht University); © Christien Klaufus.

Illustration 1. Former Sociedad Bancaria de Chimborazo, Riobamba

Illustration 2. Chalet built according to a European model in the Bellavista neighborhood, Riobamba

Riobamba

Riobamba is the capital of the homonymous canton, which is subdivided into eleven rural and five urban parroquias, and is the capital of Chimborazo Province.1 Of all provinces in Ecuador, Chimborazo has the largest share of indigenous inhabitants (Campaña 2000).2 The Quechua population figures prominently in the city, in part because the Quechua dominate the market trade. Another important factor in daily life is Riobamba's geographical location at the foot of the Chimborazo volcano, which at 6,310 meters (20,702 feet) is Ecuador's highest volcano. Around thirty-five kilometers northeast of the city is the very active Tungurahua volcano. If it erupts, large parts of the city are likely to be buried under volcanic ashes. In November 2002 the locals thought that the volcanic eruption they had feared for so long had taken place and fled en masse. Rather than a volcanic eruption, however, the explosion turned out to have come from the munitions depot at the Brigada Blindada Galápagos army barracks, situated in the northeast within the city limits. Projectiles exploded there for obscure reasons, blowing up the entire storage site. Seven people were killed and nearly 600 injured. The explosions severely damaged a large surrounding area, culminating in countless collapsed buildings—estimated at over 10,000 homes and a few monumental government buildings—and many homeless families. Very little of the aid promised in the wake of the disaster was forthcoming, and people lost much of their confidence in the civilian and military authorities. The remnants of this disaster visible to this day include torn walls and streets and makeshift restorations of buildings.

Riobamba has suffered several disasters over the centuries and even attributes its existence at its present location to a natural disaster. In 1797 the original city was destroyed by a severe earthquake. The old city of Riobamba had been situated about twenty kilometers (twelve miles) southwest of its present location, at the site of the present Sicalpa near Cajabamba (Ortiz 2005). In 1575 the Spaniards had founded the old San Pedro de Riobamba on the Puruhá settlement Liribamba, after they had established Santiago de Quito a few kilometers away in 1534. Santiago de Quito had been intended as the capital of the Real Audiencia of Quito. That same year, Quito was transferred to the north, and Riobamba expanded into the most important city in the center of the country. Around the mid-eighteenth century, Riobamba, with a population of about 8,000, was the third-largest city of the Real Audiencia of Quito, after Quito and Guayaquil. As the capital of a corregimiento, it was soon designated as a villa, a small city with certain rights to self-government (Bromley 1979). In 1799, following the destructive earthquake, the Spaniards decided to rebuild Riobamba at a different site and moved it to the Tapi highlands. In the new Riobamba, developers designed wide avenues (wider than necessary under Spanish law), low buildings, and a continuous series of parks and squares, to provide sufficient escape routes in the event of another earthquake.3 Many citizens who had survived the disaster nonetheless settled elsewhere. Only toward the mid-nineteenth century did the population of the new Riobamba equal that of the old city shortly before the earthquake (Bromley 1979: 36). Accordingly, the perception that Riobamba came into existence only “recently” influences ideas about the city.

In the nineteenth century, when Riobamba's population had been restored to the old level, a few major political events occurred that made the city the center of the nation again. In 1830 the constitution of the new republic was signed in Riobamba, which is therefore also known as the cuna de la nacionalidad, the cradle of the present ...