![]()

1 | Africa |

A Geographic Frame |

James Delehanty

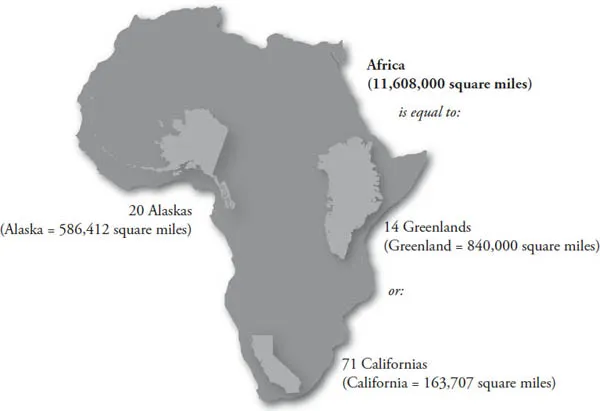

Africa is a continent, the second-largest after Asia. It contains fifty-four countries, several of them vast. Each of Africa’s biggest countries—Algeria, Congo, and Sudan—is about three times the size of Texas, four times that of France. Africa could hold 14 Greenlands, 20 Alaskas, 71 Californias, or 125 Britains. Newcomers to the study of Africa often are surprised by the simple matter of the continent’s great size. No wonder so much else about Africa is vague to outsiders.

This chapter introduces Africa from the perspective of geography, an integrative discipline rooted in the ancient need to describe the qualities of places near or distant. The chapter begins by examining how the world’s understanding of Africa has developed over time. Throughout history, outsiders have held a greater number of erroneous geographic ideas about Africa than true ones. The misunderstandings generated by these false ideas have been unhelpful and occasionally disastrous. After this survey of geographic ideas, the chapter settles into a general preference for what is true, probing, in turn, Africa’s physical landscapes, its climates, its bioregions, and the way that Africans over time have used and shaped their environments. A final section outlines the difficulties Africa has confronted and the betterment Africans anticipate as they integrate ever more fully and fairly with emerging global systems.

Knowledge of geography is a frame for deeper inquiry in all fields because the qualities of place shape every human endeavor. Anyone striving to understand the challenges and potentialities that citizens of African countries have to work with in their struggle to obtain for themselves and their families the security and prosperity that is their birthright would do well to reflect regularly on Africa’s geography. A map, especially one’s own emerging mental map of Africa, is an excellent organizing tool. It structures information according to the fundamentally interesting question “Where?” It is a solid place to start any journey, including one’s personal passage toward a more nuanced understanding of Africa.

Map 1.1. The Size of Africa.

THE IDEA OF AFRICA

Places are ideas. Consider, for example, that most significant of places, home. Every home is a physical entity—it exists concretely—but the meaning of home, its reality, is all tied up in the experiences and emotions of the people who live in that place or otherwise know it. Or consider Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh is a particular collection of buildings, roadways, rivers, people, and a great deal else occupying a defined portion of western Pennsylvania, but it also is an idea. More correctly, it is a set of ideas, because each of us has a different sense of Pittsburgh based on our views of cities in general and whatever memories and associations, accurate and false, Pittsburgh as place or word conjures in our minds when we encounter it. So too Africa. Though without doubt a continent, Africa, like all continents, also is a complex of ideas that have flowed through the human imagination, accurately and fancifully, generously and carelessly, over a great span of time, giving rise to many meanings and actions, some grounded in truth and noble, others based in error and unfortunate.

If Africa is a continent but also a product of the human imagination, the first question that must be asked is when it originated. Physical Africa, the continental landmass, is easy to date. Any basic geology text will describe how Africa took shape after the breakup and drifting apart of the pieces of the supercontinent Pangaea about 180 million years ago. As for the idea of Africa, it is somewhat more recent. The idea of Africa came into being over the last two thousand years, and it did so largely in Europe. The fact that the idea of Africa developed mostly in Europe goes a long way toward explaining how Africa is conceived worldwide, even now.

This claim—that Europeans were largely responsible for the idea of Africa—is easy to substantiate and does not discredit Africa and its people. Europeans invented America too, just as Chinese invented Taiwan and Arabs the Maghreb. All through world history, at scales ranging from the continent to the community, outsiders have given identities to places. A common way this happens is by first naming. There were no Native Americans, only hundreds of distinct peoples such as the Ojibwa of the Great Lakes and the Navajo of the western desert, until Europeans crossed the Atlantic five hundred years ago and announced the existence of a continent to be called America. Another way outsiders give identity to place is by inspiring or provoking, sometimes by threat or aggression, unity and regional loyalty where none existed before. There was no Germany until Bismarck, around 1870, convinced the German-speaking principalities of central Europe that they were one and that joining Prussia to form an entity called Germany would be in the interest of all.

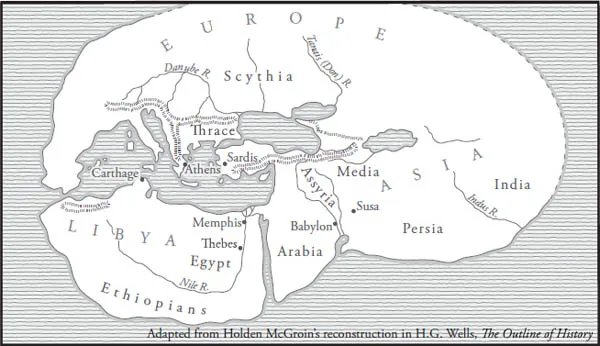

Even though few early Africans knew the bounds of the continent or could imagine Africa as a whole (the same can be said of early people on all of the continents), there were exceptions. One interesting case comes down to us from the Greek historian Herodotus, who in the fifth century BCE (Before the Common Era) wrote a brief but tantalizing report of a sea journey by Phoenicians, organized by King Necho II of Egypt, around the landmass we call Africa (which Herodotus called Libya), undertaken about two hundred years before Herodotus’s time. While no other evidence of this expedition survives, it is pleasant and plausible to believe that it occurred. If it did, then at least one small group of Africans, probably a few Phoenician adventurers from Egypt, learned of the entirety of the African landmass as long as twenty-seven hundred years ago. This knowledge appears to have died with them. It did not lead to any mapping or broad understanding within Africa of the continent’s extent. Even Herodotus knew next to nothing about what those sailors saw; he only reported the legend of their trip.

Map 1.2. The World According to Herodotus (ca, 450 BCE).

An African Circumnavigation of Africa 2,700 Years Ago

Here is the entirety of Herodotus’s account of an African circumnavigation reported to have occurred two hundred years before his time. The charming anecdote at the end, noting the strange position of the sun, inspires confidence in the story’s factuality because, unknown to Herodotus, sailors heading west at the latitude of southernmost “Libya” would see the sun on the starboard (right) side of the ship (i.e., in the northern sky) all day long, just as in Europe and most of North America the sun’s daily passage from east to west occurs entirely in the southern sky.

Libya is washed on all sides by the sea except where it joins Asia, as was first demonstrated, so far as our knowledge goes, by the Egyptian king Necho, who, after calling off the construction of the canal between the Nile and the Arabian gulf, sent out a fleet manned by a Phoenician crew with orders to sail west about and return to Egypt and the Mediterranean by way of the Straits of Gibraltar. The Phoenicians sailed from the Arabian gulf into the southern ocean, and every autumn put in at some convenient spot on the Libyan coast, sowed a patch of ground, and waited for next year’s harvest. Then, having got in their grain, they put to sea again, and after two full years rounded the Pillars of Heracles in the course of the third, and returned to Egypt. These men made a statement which I do not myself believe, though others may, to the effect that as they sailed on a westerly course round the southern end of Libya, they had the sun on their right—to northward of them. This is how Libya was first discovered by sea.

—Herodotus, The Histories 4.42 (ca. 425 BCE)

Translated by Aubrey de Selincourt

European ideas about Africa began to take shape during the period of classical antiquity. The ancient Greeks and Romans had a great deal of solid knowledge about the nearer parts of Africa. After the Roman defeat of Carthage (in present-day Tunisia) during the Punic Wars of the second century BCE, the Roman Empire expanded to encompass much of the continent’s northern reaches. The cultural and economic ties between Rome and its African provinces were strong. Northern Africa quickly became known as the granary of the empire. The word “Africa” dates from this era. It possibly comes from “Afer,” which in the Phoenician language was the name for the region around Carthage. According to this theory, Roman geographers, needing a word for the landmass to the south, borrowed “Afer,” Latinized it, and broadened its application to the entire continent south of the Mediterranean (much as Herodotus had used “Libya” in the same way, for the same purpose, a few hundred years before).

Commerce has linked Africa with the rest of the world for the last two thousand years. Never was Africa entirely isolated from the main currents of global interaction and trade. Roman coins and artifacts from the second and third centuries of the Common Era (CE) have been unearthed in lands south of the Sahara, evidence that Africa’s great desert was traversed occasionally in early days. Sailors and settlers from Borneo and Sumatra, in present-day Indonesia, traveled to Africa beginning about 350 BCE. Their descendants and language dominate Madagascar today, and the crops that these settlers carried from Southeast Asia, such as plantain, became dietary staples all across continental Africa. As early as the seventh century CE, Persian and Arab traders established outposts up and down Africa’s Indian Ocean coast, drawing commerce from the interior, linking producers in eastern and central Africa through trade with the Middle East and the wider world. There are clear records by the fourteenth century of voyages by imperial Chinese trading vessels carrying silk, porcelain, and other goods from the ports of Asia to the East African coast. The Christian kingdom of Ethiopia exchanged emissaries with the courts of Europe, including the Vatican, in the fifteenth century. And many Africans traveled great distances within the continent and beyond. A good example is Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, commonly known as Ibn Battuta, a fourteenth-century Moroccan adventurer who voyaged all across the northern third of Africa and eventually as far as China and Southeast Asia, reporting his discoveries in Arabic manuscripts read throughout the Muslim world.

These contacts of non-Africans with Africa, and the rich descriptions of portions of Africa provided to the world by outsiders and African writers such as Ibn Battuta, were elements of a partial geography of Africa. Yet an accurate cartography—a map of the continent’s position, size, and proportions—awaited the voyages of European seafarers during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and their transmittal of information to European mapmakers capable of accurately rendering Africa’s outline. In other words, despite early knowledge of many parts of Africa in many lands, including Europe, China, and the Middle East, and of course among every African who ever lived, the definition of Africa as a whole, its description as a geographic totality, fell to Europeans. And this made all the difference. Europe was poised in 1500 to rise to global dominance. The accurate and inaccurate ideas that Europeans began attaching to their categorical creation, Africa, spread around the world with European power.

What of these ideas? What did Africa come to mean in the European imagination? Portrayals of Africa and Africans in the literature and art of Europe before 1500 or so, though hardly widespread, were largely benign. That is, until about five hundred years ago European intellectuals appear to have known little about Africans (only a few people from Africa would appear now and then in the cities of Europe), and less still about Africa as a continent, but when they did consider Africa and Africans it was with a rough sort of equality. This is not to say that Europeans harbored no fantastic ideas about Africa, but their fantasies were not very much different from those constructed about many unknown lands: rumors of dragons, giants, astonishing creatures, and strange physical and cultural variations of the human family populating regions that were unbearably hot and forbidding. These were ancient motifs, long ascribed in many cultures to unfamiliar places. But Africa in Renaissance Europe was not deemed particularly backward, primitive, or frightful. In paintings Africans usually were depicted as simply another shade of human being. They were sometimes a point of interest in a picture, but no malign attention was drawn to them. Physical exaggerations or contortions were not seen. Nor in European writing of this time do we see much overt anti-African racism, only the kinds of physical and cultural speculations that were applied to unfamiliar people from all unexplored or unknown areas.

An African Description of the Nile in 1326

Ibn Battuta, a fourteenth-century Moroccan adventurer, is the most celebrated and widely read African traveler of all time. He wrote in Arabic, at great length, of his travels in Africa and all over the known world.

The Egyptian Nile surpasses all rivers of the earth in sweetness of taste, length of course, and utility. No other river in the world can show such a continuous series of towns and villages along its banks, or a basin so intensely cultivated. Its course is from South to North, contrary to all the other great rivers. One extraordinary thing about it is that it begins to rise in the extreme hot weather at the time when rivers generally diminish and dry up, and begins to subside just when rivers begin to increase and overflow. The river Indus resembles it in this feature. The Nile is one of the five great rivers of the world. . . . All these will be mentioned in their proper places, if God will. Some distance below Cairo the Nile divides into three streams, none of which can be crossed except by boat, winter or summer. The inhabitants of every township have canals led off the Nile; these are filled when the river is in flood and carry the water over the fields.

—From Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta,

Travels in Asia and Africa 1325–1354

Translated and edited by H. A. R. Gibb

(London: Broadway House, 1929)

Living standards in Europe and Africa five hundred years ago were little different. On both continents nearly everyone lived off the land, most in agriculture. Diet was unvaried. Hunger was common. Life span was short. Almost no one on either continent was well educated. Why should Europeans have considered Africans, five hundred years ago, to be in any manner inferior? There was no material reason for Europeans to stigmatize Africa and Africans in particular at this time, and generally they did not.

This changed. Increasingly in written descriptions and paintings from Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Africans took on qualities that are familiar to us now. Africans came to be defined by Europeans as poor, uneducated, technologically unsophisticated, underdeveloped, and non-Christian.

Why did this happen? Why, about five hundred years ago, did Africa in the European mind go from being a somewha...