![]()

Part One: | A Theory of Musical Narrative |

![]()

1 An Introduction to Narrative Analysis: Chopin’s Prelude in G Major, Op. 28, No. 3

When we think of narrative music, certain assumptions come quickly to mind—assumptions that have strongly colored our responses to the topic. First, narrative music is often thought to be in some way problematic or idiosyncratic; that is, we tend to resort to narrative interpretations when traditional formal, harmonic, and generic paradigms do not apply. Anthony Newcomb (1984, 1987), for example, has located a certain type of narrative music within a particularly nineteenth-century mode of expression that attaches plot archetypes to nonstandard or unusual compositional designs. Second, narrative music tends to be associated with programmaticism, dramatic or epic texts, evocative titles, or any of a variety of “attachments” that ready the listener to hear the music in a special way. Carolyn Abbate (1991) and Jean-Jacques Nattiez (1990a) have both discussed the problematic semantics of musical discourses that require supplementation. Third—and most tellingly—narrative music is typically understood as a derivative phenomenon. Its formal strategies, subject matter, and critical metalanguage are all apparently imported from literature or drama.

This book endeavors to question some of these common assumptions about narrative music and to suggest that narrative organization is far more normative and common than is generally conceded. This is not a new endeavor: Fred E. Maus, Vera Micznik, Michael L. Klein, Eero Tarasti, and others have suggested alternative ways of conceiving of narrative music and have developed powerful analytical tools to examine it. In the following chapters, I will argue that a new consensus is developing about musical narrative that is aware both of the limitations of musical expression and of the rich potential of music as a narrative medium.

Before addressing the theoretical basis and possible pitfalls of musical narrative design, let us look ahead at the ground to be covered by means of a short example. The piece to be analyzed here is Chopin’s Prelude in G major, op. 28, no. 3, chosen for its nonconformance with the traditional notions of narrative music. It does not feature a particularly unconventional formal design, and it is purely instrumental, containing no textual or programmatic cues that would suggest a narrative trajectory. Yet our analysis, derived firmly from the musical discourse, articulates just such a trajectory. This short example suggests that if we reimagine the conceptual basis of narrative theory and practice, we will find in it a rich field of study and insight.

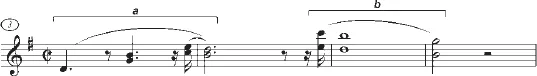

Example 1.1. Chopin, Prelude in G major, op. 28, no. 3, motives a (measures 3–4) and b (measures 4–6)

The Prelude begins with the establishment of a sixteenth-note ostinato figure that becomes the accompaniment to a lilting, dance-like melodic line. (This figure can be seen from measure 3 onward in example 1.2 below; the opening measures appear as example 5.1 in chapter 5.) The undulating, tonally stable, and repetitive character of Chopin’s ostinato figure evokes the hypnotic stasis-through-motion of the Romantic Spinnerlied, suggesting an atmosphere of rustic simplicity. It further recalls certain ubiquitous seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Figuren that appear in nature-pictorial movements and represent running water or gentle breezes. As a musical topic, we might describe the overall expressive effect as “harmony-with-nature,” nature being understood in its gentler aspect. If we trace this figure through the entire Prelude, we see that it is employed continuously, undergoing occasional changes of harmony, until the final measures. There it is doubled by the right hand and subjected to fragmentation and a registral ascent prior to the two final tonic chords that signal the work’s conclusion. Overall, one function of the topic “harmony-with-nature” in this piece is to provide a specific background environment within which the thematic material can move.

Measures 3–6 feature the first melodic phrase of the piece, which divides into two uneven subphrases distinguished by contrasting registral spaces and motivic directional contours, as shown in example 1.1.

These motives are obviously related: both are harmonically stable, and, like the accompaniment figure underneath, they both arpeggiate the tonic triad. Further, both contain short, dotted rhythmic cells that give them a lilting yet dignified quality and suggest a dance-like derivation. Despite these similarities, several musical aspects contribute to motivic contrast. The first motive, a, with its predominately half-note pulse and upward octave thrust in the piano’s middle range, is more buoyant than the second. The second motive, b, reverses the upward directionality of a, is located almost an octave higher, and contains slower note values and a decreasing dynamic level. Thus, an element of “striving upward” in a is answered by the “yielding” descent of b, but in a higher register, suggestive of distance and a lack of energy. Like the accompaniment, the a motive’s upward striving is self-contained and uncomplicated: largely arpeggiating the tonic triad, it results in an impression of assuredness rather than restlessness. Motive a’s dynamic character is reinforced by its beginning on the fifth, rather than the root, of the tonic key. The persistence of the tonic key in motive b along with the termination of that motive on the tonic pitch seems to suggest an endorsement of a’s tonal and registral motion.

The relationship between a and b, however, lies somewhere between oppositional and complementary. On the one hand, their registral separation implies a need for its removal to overcome a sense of motivic opposition. The oppositional aspect is further outlined by the contrast in directional contour, with the profile of b seeming to give way in the face of a’s ascent. On the other hand, there are rhythmic similarities between a and b that suggest an echo effect between the two motives. The anacrusis-downbeat rhythm that concludes motive a in measures 3–4 is also used to initiate motive b in measures 4–5, giving the latter motive the character of a retrograde, continuation, or reprise of the first movement. In a certain sense, a and b can be considered two halves of a larger figure—note that b inverts the intervallic content of a. Their operation suggests a kind of inner narrative, akin to what Robin Wallace (1999) has termed an “introverted reading,” in which two aspects of a single personality enter into dialogue.

Three further, more hidden aspects seem to support this interpretation. The first is the continuity of the melodic line outlined by the combined motives, which (in measures 3–5) describes a stepwise segment E-D-C-B that is hidden by the registral shift. The second aspect is the continuation of the registral ascent of motive a (D4 to B4 to D5) up to the B5 in motive b (measure 5, beat 1). The third aspect is the resemblance of the entire melodic profile a+b to the notes of the accompaniment figure. The pitches in a+b (D-B-E-D-C-B-G) are found in exactly the same order in the accompaniment figure (notes 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 13; see also measures 3–6 in example 1.2, below), and both contain the climactic neighbor-tone figure E-D. (I consider the upper line to be the melodic line, although the right-hand material is actually in parallel thirds, lending a euphoric quality to the melody. In the subsequent discussion of the melodic line, the parallel voice will be considered with respect to issues of register.)

The narrative implication, borne out in later material, is that motives a and b constitute the Prelude’s primary oppositional elements. These motives possess some form of kinship, but are prevented from realizing this kinship by two factors: their registral separation and the directionality of their melodic contours. The narrative program in this case consists of various attempts to bring the two motives into a more harmonious relationship based on the removal of these two obstacles. (Note in particular the registral overlap of a fourth, B4–E5, between the upper voice of a and the lower voice of b that will play a role in the eventual resolution of this conflict. The overlapping space thus becomes—both registrally and semantically—the area of common ground between the two motives.)

Motives a and b, thus understood, function as anthropomorphized syntactic units, or musical agents, within the meaningfully unfolding temporal process of a narrative trajectory. (See the glossary for the definition of this and other terms.) The character of this trajectory is generated by the fluctuating nature of their relationship, which sets up a semiotic opposition between the potential for relatedness and the potential for separateness. The former is musically realized by the various similarities between motives a and b: their dotted rhythmic cells, their high degree of harmonic stability, their shared initial arpeggiation of the tonic triad, and their overlapping registral compasses (the span B4–E5 is common to both). In addition, they combine to form a linear voice E-D-C-B at the middleground level, suggesting an organic connection through this hidden contiguity. This connection is reinforced by the continuation of the registral ascent of a into the beginning of motive b, preventing too great a disjunction between them. Finally, the two motives both partake of the character and shape of the accompanimental figure: apart from sharing its lilting, dignified, and dance-like quality, the composite contour of the right-hand phrase, with its staggered arch shape, is a reflection of the same shape found in the left-hand part.

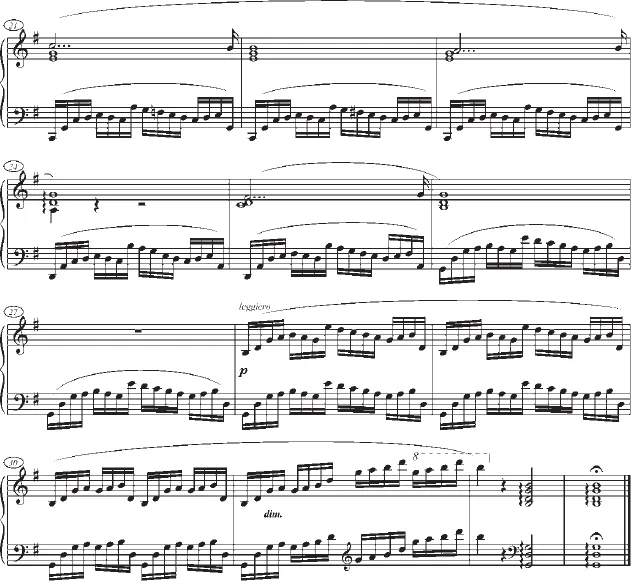

Example 1.2. Chopin, Prelude in G major, op. 28, no. 3, measures 3–33

By contrast, the potential for separation is also available to be exploited as the piece progresses. As mentioned above, this potential is primarily expressed through registral separation, contrasting directional contours, and differences in the respective sequences of rhythmic events.

This conflict between two possible paths that the music might take—toward an apparently restored unity or toward a greater degree of distinctness—can be expressed in terms of a specifically narrative opposition between an order-imposing hierarchy and a transgression of that hierarchy (discussed more fully in chapter 4). The listener must then determine the standpoint from which this opposition will be interpreted. (Is the reestablishment of an order-imposing hierarchy to be understood as desirable or undesirable? To the contrary, would a definitive departure from this hierarchy be understood as desirable or undesirable?) In this case, the topical environment plays a significant role in suggesting narrative context. Given that the peaceful, pastoral accompanimental frame, the major tonality, and the leisurely tempo all suggest calm and avoidance of conflict, the listener might be inclined to prefer a synthesis or mediation (a new hierarchical “order”) rather than a separation or “transgression.” Thus, the narrative trajectory will involve the question of whether the centrifugal elements of the two motives will lead to fragmentation or to synthesis.

What the Prelude in fact unfolds is a narrative romance, a reestablishment—through a registral and directional synthesis—of “order,” of the kinship between motives a and b.

As shown in example 1.2, measures 7–12 contain a modified version of the primary melodic material and serve to move away from relative stability and balance: the narrative action commences in an attempt to mediate between the contrasting elements from measures 3–6. The motive now in play (measures 7–8 and 9–10) is a variant of both a and b and represents a first, unsuccessful attempt at mediation between them. Its rhythmic profile most resembles a, absent the first pitch, but the lengthened initial note and the high registral location (above the aforementioned overlapping region B4–E5) suggests the less energetic b motive. The melodic profile still emphasizes an ascent, but one made less emphatic by the hesitancy of the initial appoggiatura note F♯, and the motive ends on a melodically unresolved high A. The harmonic motion away from the tonic to a tonicization of the dominant further contributes to this motive’s insufficiency as an effective mediation between a and b; its repetition, reintroducing the tonic key through the addition of a seventh to the final chord, has the effect of a halfhearted but unfruitful insistence. Leading into the second section, the repeated dotted anacruses of measure 11 present in succession the two as yet unconnected registral spans.

An exact repetition of measures 3–6 occurs in measures 12–15, including a return to the tonic—the obvious tonal location or goal for an attempt at mediation. Also recurring, however, is the original separation of melodic contour and register—the “transgression.” The difference between this passage and its earlier appearance is that the listener has now experienced the intervening material, such that measures 12–15 are no longer an initial condition, but a retreat from activity and a return to the status quo.

Measures 16–19 contain the first in a pair of phrases representing the expressive climax, phrases that together outline an octave descent from G5 to G4 (ending in measure 26). Instead of resolving the narrative conflict, the phrase intensifies it through a move to the subdominant—from the “sharp” side to the “flat” side, as it were—and an emphasis on the chromatic F♮ in measure 16. Recalling Tarasti’s (1994) notion of key regions as related to the home key as distant locales to a spatial “here,” this harmonic motion has the effect of overshooting the goal. Further, the qualities of each motive are present, but do not coexist peacefully. On the one hand, the rhythms of the melodic material derive from an almost obsessive repetition of the rhythms of the a motive, producing a sense of restless agitation. The directional profile of a, an assured arpeggiated ascent, has been replaced by a weaker reiterative figure that cannot rise higher than the F♮ but descends inevitably to E in measure 18. On the other hand, the melody appears in the register of b and displays its characteristic descent, but without the intervallic and rhythmic contour of b.

The second phrase of the pair (measures 20–27) is the crucial section with respect to the narrative, in that it enacts a resolution of the initial oppositions. This process is highlighted by an active return to tonic (IVVI) that passes through the previously tonicized subdominant and dominant regions (the harmonic locations of the earlier mediation attempts). In this section—the longest unbroken melodic span of the piece—the melodic descent combines the rhythmic profiles of a and b into a single, extended line. This passage also evokes a previous attempt at a synthesis: the rhythm in measures 21–26 is identical to the attack pattern of measures 7–10. The rhythm of a appears in measures 20–21 and, in a partially augmented form, in measures 24–26, while the rhythm of b appears in measures 22–23 and 24–25. These relationships are summarized in example 1.3.

Example 1.3. Motivic variants of a and b in the resolution passage (measures 20–26)

The registral placement also supports reconciliation, since the phrase opens within the register shared by a and b (in measures 3–6). Furthermore, the two motives are no longer separated by rests, and the melodic contour is singly directed toward the tonic pitch G, with no directional opposition as before. A synthesis of both motives, supported by rhythmic, harmonic, melodic, and registral elements, has taken place. The rhythmically assured, downbeat-oriented character of a has combined with the yielding/accepting melodic contour of b. Most importantly, since the harmonic placement of each section has functioned as a commentary on the appropriateness of the mediation, the arrival of tonic harmony in measure 26 indicates the resolution of the narrative conflict. Recalling the piece’s initial measures, the accompanimental passage in measures 26–27 clears the stage of musical agents.

The final passage of the piece (measures 28–33) features a repositioning of this accompaniment figure—the topical environment—into the foreground. As this figure ascends through the entire registral space of the piece in an effect akin to gap fill (Meyer 1956: 128–50), it effaces the narrative action, subordinating that action to the pastoral background, and restoring a sense of wholeness. The motion to the extreme upper keyboard register lends a transcendent quality, affirming the piece’s synthesizing teleology. The final two chords abstractly present the combined registral space of the accompaniment figure and the a-b synthesis. The overall effect of the postlude is to universalize the narrative action by filling the registral space and to complete the pastoral frame.

This interpretation is clearly not the o...