![]()

CHAPTER 1

Going Public

The Virus, Video, Evangelicalism, and the Anthropology of Intervention

Like the effects of industrial pollution and the new system of global financial markets, the AIDS crisis is evidence of a world in which nothing important is regional, local, limited; in which everything that can circulate does, and every problem is, or is destined to become worldwide. (Sontag 1988:180)

Our government has had no qualms about being frank to our people on issues of a national catastrophe such as the AIDS epidemic. When we came to power in 1986, the problem had already spread to most parts of the country. We opened the gates to national and international efforts aimed at controlling the epidemic. Unfortunately, despite my government’s efforts and the high level of awareness among the population, the AIDS epidemic is becoming more and more serious in Uganda. However, this awareness has, over the last few years, started paying off. (President Yoweri Museveni’s speech at the first AIDS Congress in East and Central Africa, Kampala, 1991, cited in Museveni 1992:253)

Like all interventions—whether social, legal, economic, military, technology, or public health—designed to engineer the direction or outcome of a society, Uganda’s aggressive AIDS control efforts have had profound effects beyond the primary aims of abating the spread of HIV and alleviating the suffering of those infected and affected.1 With the coming of the HIV epidemic, sexuality in Uganda as elsewhere took on new meaning and urgency. A critical anthropology of interventions reveals how HIV efforts have also contributed to the formation of new public spaces of dialogue and how these competing moralities about sexuality, gender, and the body get absorbed into local communities and their existing tensions. Uganda’s internationally recognized and funded AIDS industry thrust talk about sex and sexuality into the public domain in ways that had not been previously encountered in the country, and in many places disrupted what had been considered appropriate and age-specific social spaces for such discussions. It is these social effects of HIV-related interventions—or, the “going public of sexuality”—that form a crucial backdrop for my examination of youth sexual culture in contemporary Uganda and the anxieties surrounding it.

Woven throughout this ethnography are two larger arguments about the consequences of interventions that intensified the going public of sexuality in Uganda. First, Uganda’s HIV control efforts, which were initiated in the mid-1980s, leaned on biomedical moral authority to begin what at the time was a globally unprecedented, aggressive campaign to educate the population about acts associated with the new sexually transmitted disease, giving rise to and legitimizing the public discussion of sex. The state-sanctioned public sphere of sex talk was soon populated by the mass media and other commercialized sectors, and helped mobilize the socially conservative countermovement within the Pentecostal church. Museveni later reflected on the HIV epidemic in his autobiography, writing that the epidemic “opened the gate” for public discourses about sexuality and sexual relationships (1992:275). Second, in the process of “analysis, stocktaking, classification, and specification” of sexual practices and risk, the AIDS industry has worked to delineate and codify the population into tangible risk groups and to define the assumed characteristics of each group (Foucault 1990:24). Public health, along with other discursive regimes such as the law and the mass media, has contributed to making “youth” a more legible social category as each sector pursues its respective project and form of intervention. Understanding the conditions and implications of the going public of sexuality in Uganda is crucial for exploring, as I do in this ethnography, community-level consequences of and responses to bringing intimate relations and the sexuality of individuals into a newly configured public space. This codification and increased surveillance served to heighten not only public awareness of youth as a distinct social category, but also the moral anxiety surrounding youth sexuality. Through these transformations in the public sphere that make youth sexuality hyper-visible and incite anxiety, young people are not silently acted upon. Though structurally and economically marginalized, young people creatively appropriate and recast these same discourses as they participate in meaning-making and in imagining future possibilities in Uganda. As Mamadou Diouf observes, “the condition of young people in Africa, as well as their future, is heavily influenced by the interaction between local and global pressures: the fragmentation or dissolution of local culture and memory, on the one hand, and the influence of global culture, on the other” (2003:2)

The Marketplace for Sexual Moralities

In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (1991), Habermas argues that the public sphere emerged as a transformative space for dialogue and debate in civil society and outside the operations of the state. Written partly in response to what he saw as pessimism in prevailing Marxist theory, for which the state existed as an authoritarian regime serving the interests of capitalists, Habermas chronicles the emergence and evolving constitution of the non-state public sphere from the seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries in northern Europe as a space for rational, public debate and discourse among educated citizens. This public sphere was both a physical space (such as coffee shops and salons) and a public discourse (such as letters, newspapers, and the media), becoming an important potential “mode of social integration” for various segments of social life (Calhoun 1992:6). Yoweri Museveni’s coming to power in Uganda in the mid-1980s after twenty-five years of postcolonial state limitations on trade, speech, and human movement ushered in a new era of free mobility for goods, people, and information, facilitating an increase in the “traffic in commodities and news” (Habermas 1991:15). The emergence of the HIV epidemic along with international (humanitarian and research) interest in tackling the new disease set the stage for the creation of a public sphere around sexuality.

However, it is an oversimplification for the Western media and researchers to say that the HIV awareness campaigns “broke the silence” surrounding sexuality, implying that prior to HIV awareness campaigns there was no discussion (or at least candid discussion) of sex in Africa. As in most societies around the world, communication about sex indeed existed in Uganda in culturally appropriate and coded ways that may not be immediately obvious to outsiders. The idea that HIV campaigns “broke the silence” is not only a misrepresentation but also forecloses an investigation into how communities did and do communicate about sex, what is communicated, and what the deliberate acts of concealing and revealing can tell us about fractures in the ideal sexual culture. Instead of viewing the HIV campaigns as breaking the silence on sex, I argue that the country’s well-funded public health efforts set in motion and legitimized a rapid “going public” of sex talk that already existed in culturally appropriate and kinship-based spaces. Before the creation of the AIDS industry, sex could be considered what anthropologist Michael Taussig calls a “public secret” or “that which is generally known, but cannot be articulated”—a secret around which communities remain willfully and publicly silent, at least at the wider social level, but around which they have their own lexicon and set of codes that are communicated in particular designated spaces (1999:5). Arguing for the notion of secrecy rather than silence, Philip Setel writes, “Given this pervasive secrecy it is not difficult to see how the emerging AIDS epidemic was like turning on the lights in a room long kept intentionally dark” (1999:103). I would push this a bit further.

“Going public” has temporal and spatial dimensions. Sex talk existed but had been heavily coded and relatively confined to socially-sanctioned age/sex groups and with the “room long kept intentionally dark.” Spatially, the AIDS industry helped elevate discussions of sex from the level of space-specific and coded talk to a public level where sex became subject to wider debate and witnessing, and where the conversation was extended to previously excluded members. In other words, what changed was not that people were now talking about sex, for it was indeed an important topic of discussion in Iganga long before HIV campaigns. For instance, sexually explicit songs performed during Basoga twin-naming ceremonies or, as explored in Chapter 4, intergenerational sexual learning between a betrothed girl and her paternal aunt played major roles in the transmission of ideas about sexuality. Rather than a rupture in which sexuality became a topic for discussion, what the AIDS industry offers legitimacy to, increases the visibility of, and invites wider participation in is the public circulation of discourses of sexuality. The permeability of spaces and locations further characterized the public sphere as an arena of participation not only for the educated or middle-class but, to some extent, for the masses who consumed these public ideas and commodities. Important here is that “public discourse must be circulated, not just emitted in one direction” (Warner 2002:71). In the circulated discourse, recognizable “catchphrases,” Warner observes, “suture it to [everyday] informal speech, even though those catchphrases are often common in informal speech only because they were picked up from mass texts in the first place” (ibid.).

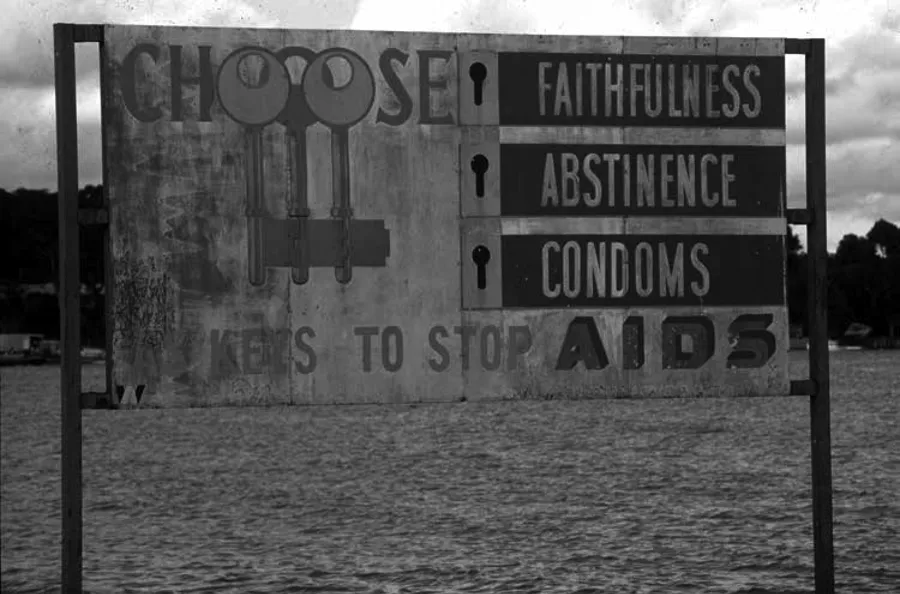

FIGURE 1.1. ABC (abstinence, be faithful, and use condoms) billboard, built in the late 1980s

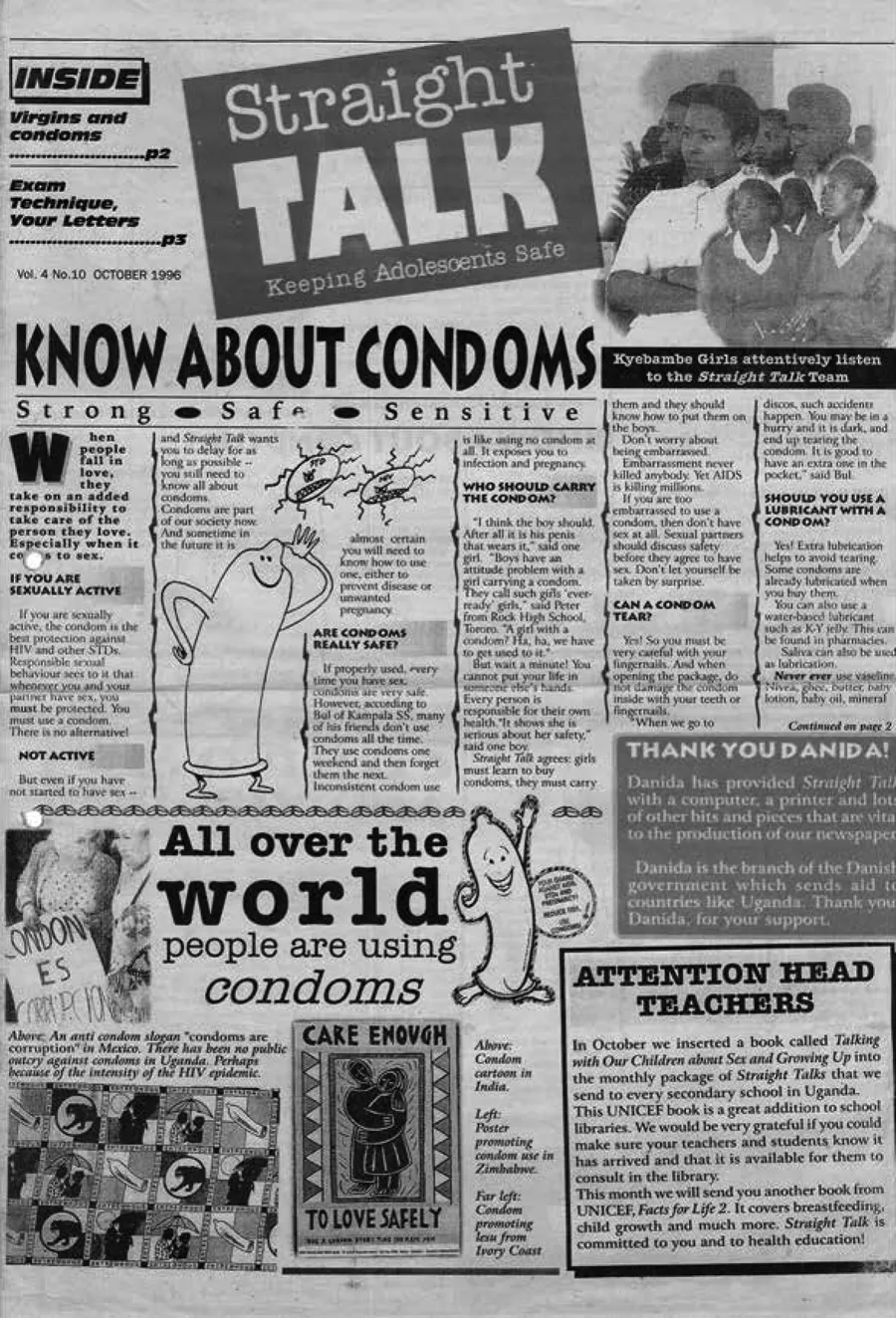

Mass-mediated technologies led to a reconfiguration or rearrangement of social categories, or as Lawrence Birken (1988) observes, a “democratization of sexual information,” in which a genderless and ageless public consumes an abundance of images (see also Frederiksen 2000). In Uganda, this has meant that the sexual learning of young people shifted from kin networks to the public sphere, further threatening the already fading system of sex education for youth. The proliferation of sex talk in the public sphere broke down preexisting generational and gender lines that determined appropriate access to information and discussions about intimacy and sexuality. Billboards about condoms or sexual networking, for instance, are visibly accessible to all ages and genders at all times, regardless of culturally specific ideas about the rolling out of sexual learning. This seemingly indiscriminate presence of sex in public—the democratization of sexual information—makes many older residents uncomfortable and lies at the heart of critiques of contemporary public sex culture. Importantly, as Warner points out, engaging with the public sphere in which circulation and reflexivity are key requires little individual investment, for “merely paying attention can be enough to make you a member” (Warner 2002:53). Because membership into public sex talk is not exclusive and because public health campaigns are considered an extension of state services (regardless of the funding sources), HIV campaigns became prime targets of scrutiny by an increasingly vocal group of social conservatives. Campaigns were routinely accused of encouraging promiscuity by offering ways to make sex safe (as opposed to discouraging sex altogether). One early campaign was the first condom promotion for youth, which appeared on the front page of the widely circulated and praised Straight Talk newspaper insert (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2. Straight Talk condom campaign, 1996

In addition to the medico-moral authority that legitimized sex going public, Museveni’s economic liberalization policies provided the foundation and incentives for private industry and media outlets to flourish. In the authoritarian periods before Museveni, the state had exercised its power through the control of media and transportation networks, constraining the movement of information and people around the country. The infamous troops at road checks who harassed and stole from citizens created a situation in which the flow of goods and information “remained strictly regulated, serving more as instruments for the domination of the surrounding areas than for the free commodity exchange” (Habermas 1991:15). Museveni’s project of “disciplining” the military and police led to a decrease in threats and acts of violence against citizens and facilitated an opening up of movement. The same long-distance road networks that carried HIV throughout Uganda and east Africa a decade earlier now freely carried the exchange of goods, information, and people, resulting in the familiar intertwining of sexual and capitalist geographies. For example, retail shops marketing modern love, romance, and sexuality in products such as clothing and self-help books were able to flourish under Museveni’s regime.

A group of young people whose parents had fled Uganda during the political turmoil between the 1960s and early 1980s were instrumental in the formation of popular media and the commercial sector. Returning to Uganda, members of this elite “bentu” class (as in “been to” London or the United States and back) brought into Uganda’s burgeoning public sphere new media genres, commercial establishments, and messages that linked sexual pleasure and desire with being modern and global. This is not to say that the media, public health, or other sectors had not provided such messages previously, but rather that the calming of the previous civil unrest and the urgency of HIV led to an opening up of Uganda and intensified the publicness, purpose, and legitimacy of sex talk.

Uganda’s globally traveled bentu had seen how the commercialization of pleasure elsewhere in the world was profitable. The bentu played a major role in how global aesthetics and ideas about modern sexuality have been incorporated and adopted into diverse Ugandan social landscapes. If we accept Arjun Appadurai’s 1996 theory of a new global cultural economy, which, he argues, “cannot any longer be understood in terms of existing center-periphery models,” then the importance of the bentu as cultural brokers who brought ordinary Ugandans to the center of internationally influenced meaning-making becomes clear (32). Their pursuit of entrepreneurial possibilities led to the entry of magazines, radio programs, newspapers, and advertisements into the newly legitimate public conversation of sex, capitalizing on citizens’ desires to engage with ideas, goods, and discourses circulating in the global marketplace (Figure 1.3). The growth of this sector is particularly visible in the controversial but popular tabloids, which offer people sensationalized news about scandals and sex. As journalist Xan Rice writes in the Atlantic, “although Uganda’s leaders like to portray themselves as the guardians of a deeply conservative, Christianity-based culture, Uganda has developed what is perhaps Africa’s most sensationalist, predatory, and lurid tabloid press” (2011).

FIGURE 1.3. Monitor gossip columns, mid-1990s

For most youth in Iganga, however, the images that inform their romantic imagination remain economically and socially unobtainable realities, and gender relations still remain largely based on historically produced inequalities. Similarly, reflecting on the mass media in Egypt, Lila Abu-Lughod calls into question the ability of the media to create democratic information flow among women in her study, creating instead a state of social delusion: “The media produces a false sense of egalitarianism that distracts from the significant and ongoing problems of class inequality in Egypt” (1995:53). In Uganda, this dissonance between the constrained realities of everyday life and the lofty promises of modern love adds to the increasing anxiety surrounding youth romance, with older people in Iganga fearing the consequences of young people’s pursuit of the unobtainable.

In sum, Museveni’s liberalization policies and disciplining of state police and the emergence of the bentu class ushered in a vibrant media and commercial economy that allowed the general public to consume various images and messages about sex in daily newspapers, radio shows, billboards, magazines, advertisements, and gossip columns. Public health conceptions of individualized sexual responsibility and risk initially shaped the public space of sex talk in Uganda, but that quickly changed as alternative dominant discourses emerged. While the AIDS industry and the public health sector circulated discourses of risk and death, the commercial sector, and particularly Uganda’s burgeoning mass media, brought onto the public stage the topics of pleasure, love, and desire. What was created was a lucrative “marketplace for sexual information” (Parker and Gagnon 1995:7) that produced multiple messages about sex for an eagerly consuming, though differentiated, public.

Surveillance, Regulation, and the Incitement to Discourse

Whereas for Habermas intellectuals and entrepreneurs who create and participate in the public sphere provide opportunities for social transformation, Michel Foucault would suggest that these people of power are far from benign agents of social change; rather, through their collective participation, these people with influence deploy new forms of specialized authority that reinforce control over ordinary citizens and society. Foucault’s general understanding about the relationship between power and those who produce knowledge leads him to conclude that the professionalization of intellectuals stimulates the emergence and refining of tools of social domination and control over populations and bodies, not the freedom of the masses. In The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, Foucault argues that in northern Europe, the eighteenth century was the age of the development of scientia sexualis, the sciences of knowledge about sexuality (namely, medicine, religion, criminology, and population sciences). The emergence of sciences of sexuality led less to “a discourse on sex than . . . a multiplicity of discourses on sex produced by a whole series of mechanisms operating in different institutions” (1990:33; Foucault’s emphasis). There was “a dispersion of centers from which discourse emanated, a diversification of their forms” (34). The “explosion of distinct discursivities” of sex occurred such that official discourse about sex was no longer the exclusive domain of Catholic confessionals, as it had been previously. Catholicism’s moral authority on sexuality began to weaken in the nineteenth century with the rise and professionalization of medical and population sciences, with each profession producing and training people in its specific tools and language that were aimed at documenting and analyzing data on the sex lives of its clients. The confessional as a hierarchical communication activity between clergy and laymen spread from the Catholic Church to the emerging centers of knowledge, becoming the method through which clients revealed their sexual idiosyncrasies and “deviances” to a new cast of professionals. Through the practice of the confessional, systems of data collection emerged for the nascent fields of science such as psychiatry, population sciences, and medicine (see also Nguyen 2010).

This proliferation of scientific centers of knowing created various discourses (or sets of knowledge) on “proper” sexuality through the “processe...