![]()

1 The Detection-Based Approach: An Overview

Scott Jarvis

Introduction

The overarching goal of this book is to contribute to the field of transfer research. The authors of the various chapters of the book use the term transfer interchangeably with the terms crosslinguistic influence and crosslinguistic effects to refer to the consequences – both direct and indirect – that being a speaker of a particular native language (L1) has on the person’s use of a later-learned language. In the present book, we investigate these consequences in essays written in English by foreign-language learners of English from many different countries and L1 backgrounds. Our analyses focus on the word forms, word meanings and word sequences they use in their essays, as well as on the various types of deviant grammatical constructions they produce. Although some of our analyses take into consideration the types of errors learners produce, for the most part our analyses are indifferent to whether learners’ language use is grammatical or ungrammatical. What we focus on instead is the detection of language-use patterns that are characteristic and distinctive of learners from specific L1 backgrounds, regardless of whether those patterns involve errors or not. We acknowledge, however, that what makes these patterns distinctive in many cases is, if not errors, at least under-uses and overuses of various forms, structures and meanings.

The novel contribution of this book is seen in its focused pursuit of the following general research question, which has only rarely received attention in past empirical work: is it possible to identify the L1 background of a language learner on the basis of his or her use of certain specific features of the target language? The potential for an affirmative answer to this question offers a great deal of promise to present and future ventures in transfer research, as I explain in the following sections. At a broad level, this area of research encompasses both the psycholinguistic ability of human judges to detect source-language influences in a person’s use of a target language, and the machine-learning capabilities of computer classifiers to do the same. In the present volume, we give only brief attention to the former phenomenon because the main focus of the book is the latter. Also, although we are interested in multiple directions of transfer, such as from a second language (L2) to a third language (L3) or vice versa, as well as from a nonnative language to the L1, for practical reasons we have decided to focus almost exclusively on L1 influence in this book, which should be seen as an early attempt to adopt, adapt and further develop new tools and procedures that we hope can later be applied to the investigation of other directions of crosslinguistic influence.

The Aims of This Book in Relation to the Scope of Transfer Research

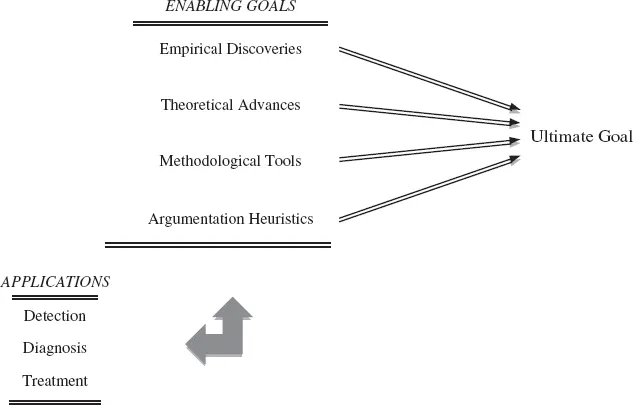

In a book-length synthesis of the existing literature on crosslinguistic influence, Aneta Pavlenko and I have stated that ‘the ultimate goal of transfer research [is] the explanation of how the languages a person knows inter act in the mind’ (Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008: 111). Most transfer research to date has not focused directly on this goal, but has nevertheless contributed indirectly to it through work on what can be described as enabling goals, or areas of research that lead to the ultimate goal. Figure 1.1 depicts the four primary enabling goals of transfer research as I see them. The first is the pursuit of empirical discoveries that expand our pool of knowledge and understanding of crosslinguistic influence. The second involves theoretical advances that explain existing empirical discoveries and additionally offer empirically testable hypotheses about what transfer is, what its sources and constraints are, what mechanisms it operates through and what its specific effects are. The third enabling goal relates to the development of methodological tools, techniques, procedures and conventions for testing those hypotheses and especially for disambiguating cases where crosslinguistic effects are hidden, obscured by other factors or otherwise uncertain. Finally, the fourth enabling goal involves the development of an argumentation framework that sets standards for (a) the types of evidence that are needed to build a case for or against the presence of transfer; (b) how those types of evidence can and should be combined with one another in order to form strong, coherent arguments; and (c) the conditions under which argumentative rigor can be said to have been achieved. These four enabling goals overlap to a certain degree and also feed into one another in such a way that advances in one area often drive advances in another.

Figure 1.1 The scope of transfer research

Figure 1.1 shows that the scope of transfer research also includes applications, which are defined as areas of research and other forms of scholarly activity that are not necessarily intended to lead toward the ultimate goal, but instead tend to be directed toward the development of practical applications of what is known about crosslinguistic influence and its effects. Broadly speaking, the applications of transfer research include the detection of instances of crosslinguistic effects (e.g. for forensic purposes), the diagnosis or assessment of transfer-related effects (e.g. for pedagogical or curricular purposes), and the development and implementation of treatments or interventions intended to minimize negative and/or maximize positive cross-linguistic effects (e.g. in order to help individuals or even whole communities achieve their language-related objectives). Progress in the pursuit of these applications often relies on discoveries and developments in research directed toward the enabling goals, but sometimes the inherited benefits are in the opposite direction. Scholarly work on transfer can sometimes also result in simultaneous advances in both areas – enabling goals and applications.

We believe that this is true of the present book, which is dedicated to the advancement of transfer research in relation to three of the enabling goals (empirical discoveries, methodological tools and argumentation heuristics) and one of the applications (detection). The first two of these goals constitute the main focus of this book, whose chapters are dedicated to the empirical discovery of new facts about transfer through the adoption and refinement of methodological tools that are new to transfer research. The remaining enabling goal also receives a fair amount of attention in this book given that the detection-based approach is strongly motivated by recent work on transfer argumentation heuristics (Jarvis, 2010). Although it is not the main focus of this book, argumentation heuristics are discussed at length in the next section of this chapter, and are also given attention by the authors of the empirical chapters of this book, who interpret their results in relation to the extent to which successful L1 detection owes to L1 influence versus other factors that may also coincide with learners’ L1 backgrounds. In connection with these interpretations, the authors also consider additional types of evidence necessary to establish the nature and extent of L1 influence in the data. Finally regarding applications, even though this book is primarily research-oriented, we do give some attention to the practical applications of this type of research. We do this partially as an acknowledgement that the available tools and methods for this type of research - and also many of the relevant previous studies - have arisen largely out of practical pursuits. I describe these in more detail in the section ‘Detection Methodology’. Additional practical considerations are brought up in relevant places throughout the book, with a detailed discussion on practical applications given in the epilog.

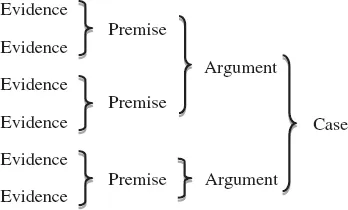

Argumentation Heuristics

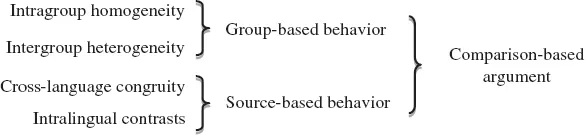

The first point in relation to argumentation heuristics is that any argument for or against the presence of transfer requires evidence, and in most cases, it requires multiple types of evidence. Often, complementary types of evidence combine with one another into premises that serve as the basis for a coherent argument either for or against the presence of transfer. Those arguments can then be used in combination with one another in order to present a case for transfer, where case refers to a comprehensive set of arguments resting on all available types of evidence (see Figure 1.2). In Jarvis (2000), I proposed an argumentation framework for transfer that relies on three types of evidence, which I referred to as intragroup homogeneity, intergroup heterogeneity and cross-language congruity. Intragroup homogeneity refers to the degree of similarity that can be found in the target-language (TL) use of speakers of the same source language (such as the L1), intergroup heterogeneity refers to TL performance differences between speakers of different source languages and cross-language congruity refers to similarities between a person’s use of the source language and TL. Recently, I have recognized the importance of a fourth type of evidence for transfer, which I refer to as intralingual contrasts. This involves differences in a person’s use of features of the TL that differ with respect to how congruent they are with features of the source language (see Jarvis, 2010).

Figure 1.2 Argumentation hierarchy

Figure 1.3 shows how these four types of evidence work together in pairs to form premises, which in turn contribute in complementary ways to the same overall argument. That is, intragroup homogeneity and intergroup heterogeneity combine with each other to demonstrate whether (or the degree to which) learners’ behavior in a TL is group based - that is, where a particular pattern of behavior is fully representative of one group (i.e. group representative) and not of others (i.e. group specific). Similarly, cross-language congruity and intralingual contrasts combine with each other to demonstrate whether (or the degree to which) their behavior is also source-language based - that is, reflecting characteristics of the source language (i.e. source like) and/or showing varying patterns of behavior at precisely those points where the relationship between the source and target languages varies (i.e. source stratified). These two premises and the four types of evidence they rest on are derived through a series of comparisons, and they work together to form what I refer to as the comparison-based argument for transfer. Transfer research that collects and presents evidence in this manner follows what I correspondingly refer to as the comparison-based approach.

It is interesting that the same combinations of evidence can sometimes be used to form different premises that serve as the basis for differing (but complementary) arguments for transfer. For example, the pairing of intragroup homogeneity and intergroup heterogeneity can be used not just for comparison purposes, but also for identification and detection purposes. In the comparison-based approach, these types of evidence are used essentially to confirm whether patterns of TL use found in the data are reliably group specific. However, a complementary argument for transfer can be made from exactly the opposite perspective, using exploratory rather than confirmatory procedures. That is, rather than measuring intragroup homogeneity and intergroup heterogeneity with respect to preselected language forms, functions and structures, we can cast our net more broadly over the data and allow patterns of intragroup homogeneity and intergroup heterogeneity to emerge on their own.1 Any such patterns, if reliable, would be indicative of group-specific behaviors, and the patterns themselves could be treated as artifacts of group membership. Such a technique could potentially be sensitive to (and likewise confounded by) multiple interweaving systems of group memberships (e.g. genders, proficiency levels, L1 backgrounds), but if the technique is tuned to focus narrowly on the artifacts of L1-group membership, and if potentially confounding variables have been controlled, then the accuracy with which learners’ L1s can be detected on the basis of those artifacts serves as a valuable indicator of the presence of crosslinguistic effects. Stated in somewhat different terms, it serves as the fundamental premise for what I refer to as the detection-based argument (see Figure 1.4); the methods, techniques, and tools associated with it correspondingly constitute what I call the detection-based approach (see Jarvis, 2010).

Figure 1.3 The comparison-based argument for transfer

Whether the detection-based argument is as strong as the comparison-based argument depends on the nature of one’s data and on how well potentially intervening variables have been balanced or controlled. In previous work (Jarvis, 2000; Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008), I have emphasized that methodological rigor requires the researcher to consider multiple types of evidence and to avoid making claims either for or against the presence of transfer on the basis of a single type of evidence. Further reflection has nevertheless led me to recognize that there are two ways of achieving what I will henceforth refer to as argumentative rigor. The most straight forward way of achieving argumentative rigor actually rests on only a single type of evidence, but it also requires showing exhaustively that the presence of that evidence is uniquely due to transfer, and cannot possibly be explained as the result of any other factor. This would constitute a rigorous argument for transfer. However, given the complex ways in which language interacts with other factors, it is rare to find patterns of language use that have only a single explanation. For this reason, I continue to emphasize the value of the previously mentioned route to argumentative rigor, which requires multiple types of evidence, any of which by itself may not be uniquely attributable to transfer, but the collection of which may indeed be difficult to account for as the result of any other factor. Crucially, the rigor of an argument is not determined by the number of types of evidence found, but rather by the researcher’s ability to rule out alternative explanations for those pieces of evidence. This means that the strength of a detection-based argument in relation to a comparison-based argument is likely to vary depending on the nature of the data and the degree to which the effects of other, potentially confounding factors have been controlled or otherwise accounted for.

On another level, it is also important to recognize that the comparison- and detection-based approaches have complementary strengths and weaknesses in relation to the types of errors they help us avoid. Statisticians refer to Type I and Type II errors, which can be described as false positives and false negatives, respectively. In the context of the present discussion, a Type I error would be one where the researcher concludes that L1 effects are present when in fact they are not (i.e. a false positive). A Type II error would correspondingly involve the interpretation that L1 effects are not present when in fact they are (i.e. a false negative). In my previous work on argumentative rigor (Jarvis, 2000, 2010; Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008), I have been concerned mainly (though implicitly) with the avoidance of Type I errors, which the comparison-based approach appears to be especially well suited to prevent due to its reliance on so many types of evidence related to both group-specificity and source-language-specificity. Recently, however, I have become increasingly concerned about Type II errors and the possible real L1 effects that researchers may continually overlook – like fish in a pond that are never seen or caught until the right tools and techniques are used. For reasons that will become clear in the next section of this chapter, the exploratory techniques associated with the detection-based approach are well suited to detecting subtle, complex, and unpredicted instances of L1 influence that can easily be overlooked – and may not even be anticipated – in the comparison-based approach, and these techniques give the detection-based approach certain advantages over the comparison-based approach in relation to the prevention of Type II errors.

Figure 1.4 The detection-based argument for transfer

The detection-based approach may be particularly useful for investigating indirect L1 effects where source-language-specificity is elusive – that is where learners’ TL behavior does not reflect their L1 behavior, but where learners’ perceptions and assumptions about the relationships between the L1 and TL do nevertheless affect how they navigate their way through the learning and use of the TL. Such effects might be found, for example, in learners’ patterns of avoidance, where they avoid using features of the TL that are different from the L1 in a way that makes those features seem difficult to use (e.g. Schachter, 1974). Indirect L1 effects might also be found in the ways in which the L1 constrains the range of hypotheses that learners make about how the TL works (cf. Schachter, 1992), such as when Finnish-speaking learners of English use in to mean from – something that learners from most other L1 backgrounds do not do, and also something that Finnish speakers themselves do not do in their L1, but which is nevertheless motivated by abstract principles of the L1 (Jarvis & Odlin, 2000). Indirect L1 effects in which TL behavior is not congruent with L1 behavior also involve cases where learners’ TL behavior is neither L1-like nor target-like, but instead either (a) reflects compromises between both systems (e.g. Graham & Belnap, 1986; Pavlenko & Malt, 2011) or (b) involves the relaxing of TL constraints that are incompatible with L1 constraints (cf. Brown & Gullberg, 2011; Flecken, 2011). Other cases of indirect L1 effects in which evidence of cross-language congruity is difficult to find involve cases where the TL has a feature that does not exist in the L1 (e.g. articles or prepositions), or where corresp...