![]()

This book is about a biological organ, the brain, and what it does, the mind.

As with all body parts, evolution has adapted brains to suit particular environments and ways of life. If the brain has evolved, and is the vehicle of the mind, does it follow that the mind has also evolved? The answer to this question must be both “Yes” and “No”. The brain and “biological mind” of primates evolved for life in the jungle or out on the savannah. They are adapted to solve the particular problems of finding food and shelter, of reproducing and caring for young.

However, in addition to being an evolved “biological mind”, the human mind is also a “cultural mind” socialized in how to solve a host of “unnatural” problems thrown up by the invention of music-making and reading, painting, computer-programming and voting in elections. The cultural mind is reflexive – it reflects upon itself. To an extent, the mind is how we talk and think about it.

Mind and Brain: a Brief History

Human beings have known about the brain for a long time without being at all clear exactly what it is for. The large number of early hominid skulls which show signs of deliberate damage suggest that by three million years ago our predecessors had at least worked out that the brain is a vital organ.

The opening scene from Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi film classic, 2001 (1968), depicts our hominid ancestors discovering homicide.

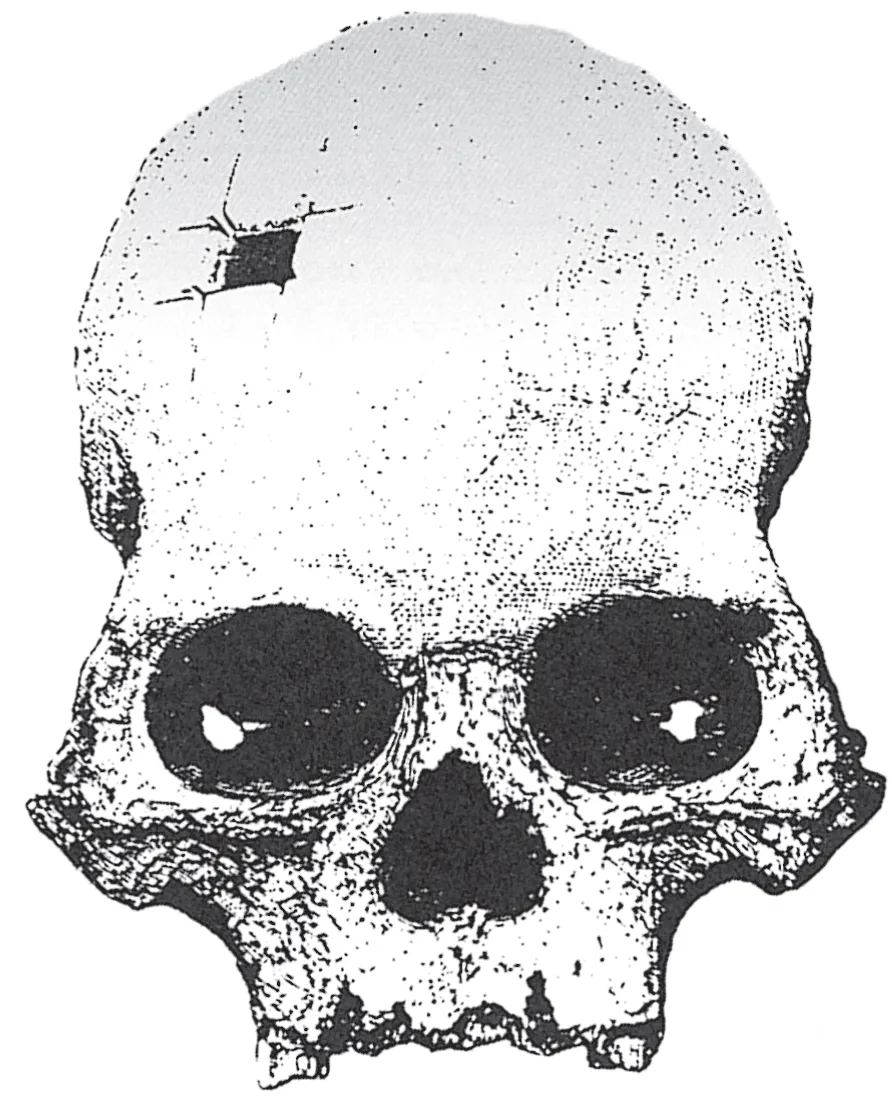

A better-intentioned knowledge was in evidence by 10,000 years ago. Neolithic skulls from around the world exhibit holes trepanned – that is, scraped or drilled – in them. The holes jj have smooth edges and show H clear signs of healing.

Trepanning was practised until relatively recent times in Europe, and continues in many cultures. Theoretical arguments for the modern technique of electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) are scarcely stronger than those for trepanning.

When Neolithic “doctors” trepanned a “patient”, did they believe they were treating the body, the mind, the spirit or the soul? We can never know. But they probably would not have recognized these distinctions.

Inventing the Mind

The epic poems of Homer in the 8th century B.C. are Europe’s earliest substantial pieces of writing. The Iliad recounts the Siege of Troy and the Odyssey tells of the journey home from Troy of the hero Odysseus (Ulysses to the Romans).

Amazingly, these works scarcely refer to what we would call “The Mind”. Homer’s vocabulary does not include mental terms such as “think”, “decide”, “believe”, “doubt” or “desire”. The characters in the stories do not decide to do anything. They have no free will.

Where we would refer to thinking or pondering, Homer’s people refer to speaking to or hearing from their own organs: “I told my heart”, or “my heart told me”. Feelings and emotions are also described in this half-strange, half-familiar manner. Feelings are always located in some part of the body, often the midriff. A sharp intake of breath, the palpitating of the heart, or the uttering of cries is a feeling. A feeling is not some inner thing separate from its bodily manifestation.

The Iliad and Odyssey are written versions of “songs” originally sung by non-literate bards that expressed the beliefs and ideas of their oral culture.

People in oral cultures do not explicitly recognize the difference between a thought and the words which express it. What you say is what you intend. Your word (not your signature) is your bond. Speech is gone the moment it is uttered. Written records, by contrast, stay fixed. You can study them at leisure. This encourages a distinction between the persisting symbols on the page and the ideas they represent. “Literal” meaning gets consistently discriminated from “intended” meaning (as in the “letter” and the “spirit” of the law).

The ratio of rational thought branches off from the oratio of speech to become a separate concept. People’s actions express their thoughts and decisions they have made.

Literacy, it is argued, drives a wedge between two worlds. One is the world we hear and see, the world of talk and action. The other is the imperceptible mental world of thoughts, intentions and desires. Just as talk and action take place within the physical world, so literate Greeks at the time of Plato and Aristotle created a space in which to house thoughts, intentions and desires. This metaphorical space was first called the psyche, but now is known as the mind.

What is the Mind?

We can see that this question has no simple...