eBook - ePub

Leaders

Warren G. Bennis, Burt Nanus

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 256 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Leaders

Warren G. Bennis, Burt Nanus

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

In this illuminating study of corporate America's most critical issue—leadership—world-renowned leadership guru Warren Bennis and his co-author Burt Nanus reveal the four key principles every manager should know: Attention Through Vision, Meaning Through Communication, Trust Through Positioning, and The Deployment of Self.

In this age of "process", with downsizing and restructuring affecting many workplaces, companies have fallen trap to lack of communication and distrust, and vision and leadership are needed more than ever before. The wisdom and insight in Leaders addresses this need. It is an indispensable source of guidance all readers will appreciate, whether they're running a small department or in charge of an entire corporation.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Leaders un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Leaders de Warren G. Bennis, Burt Nanus en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Business y Leadership. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

BusinessCategoría

LeadershipLeading Others,

Managing Yourself

Among the most difficult questions about any radical paradigmatic shift are these: What do you do in the meantime? How do you prepare? What is the role of leaders and educators? These questions are simultaneously problematic and marvelous.

In an effort to better understand and participate in this age of change, we undertook the subject of leadership as the central ingredient to the way progress is created and to the way organizations develop and survive. A series of ninety interviews were conducted, sixty with successful CEOs, all corporate presidents or chairmen of boards, and thirty with outstanding leaders from the public sector.

Since leadership is the most studied and least understood topic of any in the social sciences, a context for the interviews had to be created. Books on leadership are often as majestically useless as they are pretentious. Leadership is like the Abominable Snowman, whose footprints are everywhere but who is nowhere to be seen. Not wanting to further muddle the bewildering melange of leadership definitions, we set out to provide a unique and instructive framework for our investigation: the present.

It almost seems trite to say it, but we must state the obvious. Present problems will not be solved without successful organizations, and organizations cannot be successful without effective leadership. Now.

A business short on capital can borrow money, and one with a poor location can move. But a business short on leadership has little chance for survival. It will be reduced to the controls of, at best, efficient clerks in narrow orbits. Organizations must be led to overcome their “trained incapacity” and to adapt to changing conditions. Leadership is what gives an organization its vision and its ability to translate that vision into reality. Without this translation, a transaction between leaders and followers, there is no organizational heartbeat.

The study pursued leaders who have achieved fortunate mastery over present confusion—in contrast to those who simply react, throw up their hands, and live in a perpetual state of “present shock.”

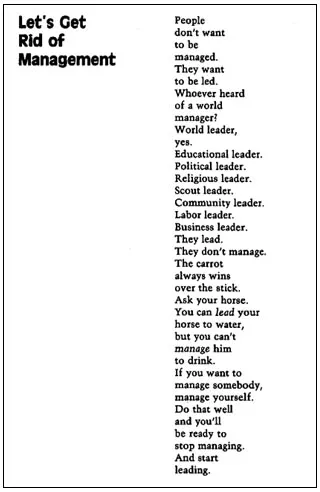

The problem with many organizations, and especially the ones that are failing, is that they tend to be overmanaged and underled (see figure 1). They may excel in the ability to handle the daily routine, yet never question whether the routine should be done at all. There is a profound difference between management and leadership, and both are important. “To manage” means “to bring about, to accomplish, to have charge of or responsibility for, to conduct.” “Leading” is “influencing, guiding in direction, course, action, opinion.” The distinction is crucial. Managers are people who do things right and leaders are people who do the right thing. The difference may be summarized as activities of vision and judgment—effectiveness—versus activities of mastering routines—efficiency.

Thus, the context of leadership that all those interviewed both shared and embodied was directly related to how they construed their roles. They viewed themselves as leaders, not managers. This is to say that they concerned themselves with their organizations’ basic purposes and general direction. Their perspective was “vision-oriented.” They did not spend their time on the “how tos,” the proverbial “nuts and bolts,” but rather with the paradigms of action, with “doing the right thing.”

Furthermore, the study concentrated on leaders directing the new trends. There were no “incrementalists.” These were people creating new ideas, new policies, new methodologies. They changed the basic metabolism of their organizations. These leaders were, in Camus’s phrase, “creating dangerously,” not simply mastering basic routines.

Fig. 1. A message as published in the Wall Street Journal by United Technologies Corporation, Hartford, Connecticut 06101.

The “methodology” we used—if that’s the proper word to apply, and we doubt it—was a combination of interviewing and observations. Like many fascinating (and fascinated) people, the ninety leaders had as many questions as answers. The “interviews” became more like exploratory dialogues and the so-called subjects became our coinvestigators. In most cases, the topic of leadership was discussed in three or four hours; in ten cases, we spent about five days with the leader (in two of those cases we actually lived with the leader, commuted to work with him, and got to know “the family” and the leader’s staff and board members) in an attempt to learn about the organizational culture over which he presided.

The dialogues were “unstructured”; that is, they proceeded in an informal, rambling manner and were led only vaguely and intermittently by us. We went about these discussions much the way oil drillers go after oil. You chivvy around for the best position for the drill and keep probing and testing until you “hit.” Then you stay there until it dries up. Then move on to another spot. There were only three questions asked of all leaders: “What are your strengths and weaknesses?” “Was there any particular experience or event in your life that influenced your management philosophy or style?” (There almost always was.) “What were the major decision points in your career and how do you feel about your choices now?” Those questions were the pivots around which the entire discussion revolved and they elicited rich, lively, and juicy responses. There’s no other way to describe them.

Those interviewed included William Kieschnick, CEO of ARCO;* Ray Kroc of McDonald’s fame; Franklin Murphy, chairman of Times-Mirror; Donald Seibert, chairman of JCPenney; John H. Johnson, publisher of Ebony; Donald Gevirtz, chairman of the Foothill Group; and James Rouse, chairman of Rouse Company. The public sector was much more varied: university presidents, the head of a major government agency (Harold Williams, former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission), coaches (John Robinson of the University of Southern California and Ray Meyer of DePaul University), orchestra conductors, and public interest leaders such as Vernon Jordan, former head of the Urban League. In addition, there was E. Robert Turner, former city manager of Cincinnati; William Donaldson, president of the Philadelphia Zoological Society; and Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, who personifies the genuine all-American hero.

It was a search for similarities in a wildly diverse group. Roughly half of the 60 CEOs were from Fortune’s top-200 list. The remainder were from smaller companies and enterprises. The median age (for the Corporate America group) was 56, the average income $400,000 (without “perks”). The average number of years with the company was 22.5 and the number of years as CEO was 8.5. Almost all were white males, reflecting the legacy of sexism and racism in the corporate world.* Most had college degrees—25 percent with advanced degrees and about 40 percent with degrees in business—again proving the hypothesis that you don’t have to have a business degree to succeed. In short, with one exception, there were no surprises, demographically, in the CEO group; as a group, they corresponded almost perfectly to the various profiles of corporate leadership in America.1 The only surprise worth mentioning is that almost all were married to their first spouse. And not only that: They were also indefatigably enthusiastic about marriage as an institution.

Otherwise, there seemed to be no obvious patterns for their success. They were right-brained and left-brained, tall and short, fat and thin, articulate and inarticulate, assertive and retiring, dressed for success and dressed for failure, participative and autocratic. There were more variations than themes. Even their managerial styles were restlessly different. (One confided that, by nature, he believed in “participative fascism.”) For those of us interested in pattern, in underlying themes, this group was frustratingly unruly. But they also gave testimony to the multifarious opportunities that are uniquely American.

The Four Strategies

However, determined to get our “conceptual arms” around the leadership issue, we vigilantly trolled these disparate powers for uniformities, a process that eventually took about two years. And we did this much the way one decants wine or pans for gold, by continuously (and monotonously) going over the interviews and notes and trying out one concept to see how much of the data it could screen out and how much it could hold. Then another. And another. We looked to see if there were any kernels of truth about leadership—the marrow, if you will, of leadership behavior. Perhaps others would look elsewhere; for us, four major themes slowly developed, four areas of competency, four types of human handling skills, that all ninety of our leaders embodied:

- Strategy I: attention through vision

- Strategy II: meaning through communication

- Strategy III: trust through positioning

- Strategy IV: the deployment of self through (1) positive self-regard and (2) the Wallenda factor

Leadership seems to be the marshaling of skills possessed by a majority but used by a minority. But it’s something that can be learned by anyone, taught to everyone, denied to no one.

Only a few will lead nations, but more will lead companies. Many more will lead departments or small groups. Those who aren’t department heads will be supervisors. Those who follow on the assembly line may lead at the union hall. Like other complex skills, some people start out with more fully formed abilities than others. But what we determined is that the four “managements” can be learned, developed, and improved upon. And like fine wine, these competencies are the distilled essence of something much larger—peace, productivity, and perhaps freedom itself.

Strategy I: Attention Through Vision

All men dream; but not equally.

Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds

Awake to find that it was vanity;

But the dreamers of day are dangerous men,

That they may act their dreams with open eyes to make it possible.

T. E. Lawrence

Management of attention through vision is the creating of focus. All ninety people interviewed had an agenda, an unparalleled concern with outcome. Leaders are the most results-oriented individuals in the world, and results get attention. Their visions or intentions are compelling and pull people toward them. Intensity coupled with commitment is magnetic. And these intense personalities do not have to coerce people to pay attention; they are so intent on what they are doing that, like a child completely absorbed with creating a sand castle in a sandbox, they draw others in.

Vision grabs. Initially it grabs the leader, and management of attention enables others also to get on the bandwagon. We visited Ray Kroc at “Hamburger U” in Elk Grove, Illinois, near Chicago, where McDonald’s employees can get a “Bachelor of Hamburgerology with a minor in French fries.” Kroc told the circumstances of his initial vision. He was already a tremendously successful paper cup manufacturer when he began manufacturing milkshake machines. He met the McDonald brothers, who owned a chain of milkshake parlors, and that collusion of cups and shakes set off the spark—a phenomenon we now know as McDonald’s. When asked what leads to such serendipitous notions, Kroc answered, “I can’t pretend to know what it is. Certainly it is not some divine vision. Perhaps it’s a combination of your background, your instincts and your dreams. Whatever it was at that moment, I suppose I became an entrepreneur and decided to go for broke.”

Another of the survey participants was Sergiu Comissioná, the renowned conductor of the Houston Symphony. For a long time he refused to be interviewed, which was remarkable in and of itself. He wouldn’t respond to letters; he wouldn’t respond to phone calls. After many months we were able to get in touch with two of his musicians. When asked what Comissioná was like, they answered, “Terrific.” But when asked why, they wavered. Finally they said, “Because he doesn’t waste our time.”

That simple declarative sentence at first seemed insignificant. But when we finally watched him conduct and teach his master classes, we began to understand the full meaning of that phrase “he doesn’t waste our time.” It became clear that Comissioná transmits an unbridled clarity about what he wants from the players. He knows precisely and emphatically what he wants to hear at any given time. This fixation with and undeviating attention to outcome—some would call it an obsession—is only possible if one knows what he wants. And that can come only from vision or, as one member of Comissioná’s orchestra referred to it, from “the maestro’s tapestry of intentions.”

There is a high, intense filament we noticed in our leaders—similar to Comissioná’s passion about the “right” tone—and in any person impassioned with an idea. Sometimes it burns only within the range of their vision, and outside that range they can be as dull or interesting as anyone else. But this intensity is the battery for their attention. And attention is the first step to implementing or orchestrating a vision external to one’s own actions.

An actress working on a set with one of our leaders, in this case a director, commented about him: “He reminds me of a child at play…very determined…. He says, like a child, ‘I want this or I want that.’ When he explains things, it is like a child who says, ‘I want a castle built for me,’ and he gets it.” (Which brings to mind the composer Anton Bruckner, who, musing aloud to his fiancée, exclaimed, “But my dear, how can I find time to get married? I’m working on my Fourth Symphony.”)

The visions these various leaders conveyed seemed to bring about a confidence on the part of the employees, a confidence that instilled in them a belief that they were capable of performing the necessary acts. These leaders were challengers, not coddlers. Edwin H. Land, founder of Polaroid, said: “The first thing you naturally do is teach the person to feel that the undertaking is manifestly important and nearly impossible…. That draws out the kind of drives that make people strong, that put you in pursuit intellectually.”

Vision animates, inspirits, transforms purpose into action. Lincoln Kirstein, founder of the New York City Ballet and School, said: “My whole life has been trying to learn how things are done. What I love about the ballet is not that it looks pretty. It’s the method in it. Ballet is about how to behave.” And one of his associates said about him: “He has a power of concentration the likes of which I’ve never seen. He always knew what he wanted.” (That’s why it was also said about Kirstein that he never “wastes your time.”) He said about his house: “Everything in this house is didactic and serves a purpose.” Incidentally, his dress never varies: black suit, black socks, black tie, white shirt. Every day. “I long ago worked out that I would save a great deal of time if I forwent the particular choice of dress.”

Incidentally, one of Kirstein’s heroes, a namesake, is Abraham Lincoln, our sixteenth president. This choice of a hero dramatizes the significance of vision: “The superiority of Lincoln over all other statesmen,” he wrote, “lies in the limitless dimensions of a conscious self, its capacities and conditions of deployment…. In it, we see the Lincolnian self, capable of delay, double-talk, maneuver, hesitancy, compromise, in order that one prime aim of his own era be effected: preservation of Federal union.”

Listen to that pneumatic sense of purpose that comes through in Kirstein’s admiration of President Lincoln—“preservation of Federal union.” At all costs. It’s worth sacrifice, ...