![]()

1 What Are Sustainability Indicators For?

Rachael Garrett and Agnieszka E Latawiec

1.1 Introduction

Indicators are critical to both scientific inquiry and policy development in complex systems. They are concise information systems that provide quantitative and qualitative information about the condition and trajectory of a system and why certain trends occur in specified contexts (Bell and Morse, 2008). To date a wide range of sustainability indicators have been proposed by different authors and organizations (Bell and Morse, 2008; Moldan et al., 2012). The selection and use of specific indicators from among these myriad choices depends on a range of factors, including values about the goals of such indicators and appropriate temporal and spatial scales of assessment. One cannot use every indicator potentially available, so an element of simplification, while maximizing unique and relevant information, is essential. Due to these value differences regarding objectives and scope, the selection of sustainability indicators will undoubtedly involve substantial discussion within an organization. The selection of indicators will also be influenced by the availability of resources, time constraints, and data. Due to these reasons there can be no a priori “best set” of sustainability indicators within a particular sector or region. Nevertheless, the goals of this chapter are to help improve the selection of indicators for sustainability science and policy by: i) Discussing the purpose of sustainability indicators, ii) Describing the features of good and effective sustainability indicators, and iii) Presenting examples of sustainability indicators that illustrate a range of trade-offs associated with their use in practice. Before embarking on this task we briefly contextualize sustainability and begin with a definition of “sustainability” that will guide our discussion on the purpose and quality of indicators.

1.2 Components And Interpretations Of Sustainability

Sustainability is a word used broadly in scientific and policy spheres to describe conditions that do not damage the environment or degrade ecosystem services (Parris and Kates, 2003). Over the last twenty years, numerous researchers have discussed the problematic nature of the word sustainability used in this broad sense, highlighting important questions such as what exactly should be sustained and for whom, when, and why (Costanza and Patten, 1995; Parris and Kates, 2003; Marshall and Toffel, 2004). More specifically these authors ask: i) who decides what should be sustained? ii) over what time frame should it be sustained?, and iii) for what purpose?

Almost every article or book on sustainability expresses disappointment that the concept of sustainability lacks consensus. For example, Lynam and Herdt (1989) state that sustainability is ‘the capacity of a system to maintain output at a level approximately equal to or a greater than its historical average, with the approximation determined by the historical level of variability’. Pearce and Turner (1990) claim that sustainability means ‘maximizing the net benefits of economic development, subject to maintaining the services and quality of natural resources over time’. More recently, Hak et al. (2007) defined sustainability as ‘the capacity of any system or process to maintain itself indefinitely’.

Coupled with the word development, however, the term sustainability provides a slightly clearer normative and anthropocentric goal of how to use resources. Using Arrow et al. (2012)’s definition: sustainable development is development that sustains, i.e. does not decrease, the wellbeing of the current generation as well as the potential wellbeing of all future generations. This definition helps clarify the ‘who, when, and why’ of sustainability. It also provides policy goals that are slightly more ambitious than just simply not ‘compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Bruntland, 1987), by specifying that policies intended to promote development should leave future generations with ‘as many opportunities as we ourselves have had, if not more’ (Serageldin, 1996).

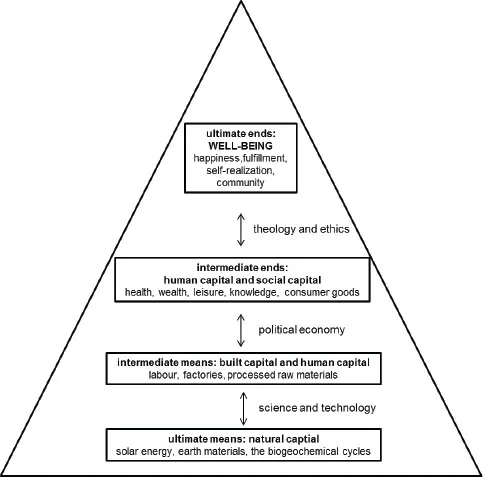

The concept of wellbeing encompasses individuals’ capacity to achieve happiness, harmony, identity, fulfillment, self-respect, self-realization, community, transcendence, and enlightenment (Meadows, 1998). It involves access to security, health, material needs, good social relations, and freedom of choice (MEA, 2005). It is inherently relational, and takes into account equity, sufficiency, and quality (Meadows, 1998). To ensure non-decreasing intergenerational wellbeing it is necessary to maintain the assets and stocks that provide the goods and services essential to wellbeing (Arrow et al., 2012). Managing a stock to provide the continued satisfaction of our wants and needs inherently involves protecting the throughputs that replenish that stock (Daly, 1991).

We can divide the assets that must be maintained into five major categories:

- – Natural capital is the quantity and quality of environmentally provided assets (such as soil, atmosphere, forests, water, wetlands, mineral resources, biogeochemical cycles, etc.) that provide a flow of useful goods or services (Serageldin, 1996). The “ecosystem services” provided by natural capital include provisioning of food, water, timber, and fiber; regulating climate, floods, disease, wastes, and water quality; culturally related recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits; as well as soil formation, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling processes that support other natural capital services (MEA, 2005). Natural capital can also be perceived as the ultimate, non-substitutable stock underlying all other capital stocks (Daly, 1991; Meadows, 1998). Humans can build a water filtration plant to provide the same services as a forest, but we cannot create water out of nothing.

- – Human capital is the quantity of the human population (size, age structure and geographic distribution), and the quality (health and capability) of that population (Serageldin, 1996).

- – Knowledge capital includes collective public awareness of how and why things are as they are (formal scientific knowledge) as well as how to fulfill human purposes in a specifiable and reproducible way (experiential technological and managerial knowledge) (Brooks, 1980; Raymond et al., 2010). The components of human and knowledge capital defined here are often combined under the heading of human capital.

- – Social capital encompasses norms and institutions and emerges from interactions between people or between people and organizations or the market. Institutions include official policies as well as informal rules, while norms include expectations about behavior, such as reciprocity and trust (Ostrom, 1986; Roseland, 2000; Ostrom, 2009).

- – Manufactured capital is the quantity and quality of physical stock that is created by humans, to provide goods and services, such as roads, houses, machinery, cars, and medicine (Serageldin, 1996).

The economy is in a “steady state” when natural, human, and manufactured capital are non-decreasing (Daly, 1991). Development is not sustainable when wealth, measured as the sum of all assets, weighted by their marginal contribution to wellbeing, is decreasing (Arrow et al., 2012). An economy that is “developing” is one in which natural, human, and manufactured stocks are non-decreasing, while social and knowledge capital are increasing (Daly, 1991), so long as increases in social and knowledge capital are contributing positively to human wellbeing.

In the selection of relevant indicators of sustainability it is important to note that some assets are substitutes, some are complements, some are both (Serageldin, 1996). Manufactured capital is undoubtedly the most substitutable stock since we create this capital from other asset groups, predominantly natural (energy), human capital (labor), and knowledge (technology). Natural capital is perhaps the least substitutable of all assets. Not only is it impossible to replace the natural capital that provides services that are directly essential to our wellbeing, such as healthy food, clean water, and clean air, but it is also impossible to replace the underlying ecosystems services that support the natural capital that provides these essential services (MEA, 2005). For example, a fishery policy that contributes to sustainable development would not only restrict harvesting, but also would protect the marine ecosystem of that fishery from damage that might harm the fish populations capacity to reproduce.

According to the capital asset theory, instantaneous and intergenerational wellbeing will move in the same direction when the economy is in a steady state (Arrow et al., 2012). For more discussion on intergenerational relations and wellbeing see chapter 2. It is also assumed, implicitly, that increases in all assets will be distributed equally. In reality it is quite likely that the total asset base for a country could stay constant while the distribution between individuals within that country changes substantially. It is even possible that some people could see their access to certain assets decreasing even as the total asset base increased. In this case, it becomes less clear that the total wellbeing of the country would be constant. Thus, distribution of assets also matters in the selection of sustainability indicators and evaluations of sustainable development (Valentin and Spangenberg, 2000).

While we have focused on a wealth-based definition of sustainability, it is worth noting that not all uses of sustainability indicators need focus on wealth accounting approaches. It may be equally functional, and less redundant to focus the study of sustainability on specific sectors and regions and to select clear indicators within these sectors and regions that can measure a clear deviation from sustainable pathways within the larger context of sustainable development (Kaufmann and Cleveland, 1995).

1.3 Why Do We Need Sustainability Indicators?

Indicators serve two major roles in the field of sustainability science. First, the selection of good sustainability indicators (or metrics) can help clarify causal relationships between specific capital assets and intergenerational wellbeing, improving knowledge about social-ecological systems as an end in and of itself. Second, the creation of good sustainability indicators can greatly aid policy and management decision-making. These roles are highly interconnected since the proper identification of causal relationships between capital assets and wellbeing in social-ecological systems can help elucidate trade-offs in wellbeing from enhancing or depleting different capital stocks.

Sustainability indicators can be drawn from a wide range of economic, social or environmental sources (Hak et al., 2009) and may contribute to all five stages of policy analysis: i) Clarifying goals, ii) Describing trends, iii) Analyzing conditions, iv) Projecting developments, and v...