eBook - ePub

Evolution of the Market Process

Michel Bellet, Sandye Gloria-Palermo, Abdallah Zouache, Michel Bellet, Sandye Gloria-Palermo, Abdallah Zouache

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 344 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Evolution of the Market Process

Michel Bellet, Sandye Gloria-Palermo, Abdallah Zouache, Michel Bellet, Sandye Gloria-Palermo, Abdallah Zouache

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This impressive volume centres on the relationship between Austrian and Swedish economics. Exploring themes such as capital theory, expectations, policy, market theory and the history of economic thought, this book makes for an interesting read. It will appeal across a wide range of disciplines within economics as well as the philosophy of social s

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Evolution of the Market Process un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Evolution of the Market Process de Michel Bellet, Sandye Gloria-Palermo, Abdallah Zouache, Michel Bellet, Sandye Gloria-Palermo, Abdallah Zouache en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Betriebswirtschaft y Business allgemein. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part I

The meeting of Austrian and Swedish economics

1 The metamorphoses of neoclassical economics

Axel Leijonhufvud

Introduction

Between the two world wars, there were still distinct traditions or ‘schools’ in economics. But interaction by correspondence and travel between the various centers of learning was increasing and there was a widespread expectation that the various traditions were merging into a unified international neoclassical discipline, perhaps even a science. With the exception, perhaps, of the relationship between the London School of Economics and Cambridge, there was in or around 1930, as yet little sense of controversial opposition between the various traditions but instead more of an appreciation of what they could learn from each other.

In or around 1930, it would, moreover, have been a reasonable expectation that this unified international economics not only would incorporate the main teachings of the Austrian and the related Swedish traditions but also that it was likely to develop in directions defined by the work then being done by the younger generation of Austrians and Swedes. Everyone acknowledged that the Lausanne School had demonstrated better than anyone else how ‘everything depended upon everything else’ but it had little influence on the research actually being done in those years. Similarly, everyone had to know their Marshall but the Marshallian tradition was not the main source of the problems and questions that interested economists at that time.

So what happened? The Stockholm School died out and today is largely forgotten. The Austrian School survived as a small minority, isolated and neglected by the mainstream, and devoted to the purification and preservation of uniquely Austrian tenets. Marshallian cost-curves kept a foothold in undergraduate textbooks but hardly anyone did Marshallian research. All three ended up, as it were, ‘marginalized’.

The standard answer to the question of what happened is that the Keynesian revolution won out over the Austrians and Swedes in macroeconomics and, I suppose, that the Hicks–Samuelson mathematization of theory in effect did the same in microeconomics. I have no objection to that answer except that it does not explain how or why this all came about.

The ‘great transformation’ of neoclassical economics

My own interest in this question has a macroeconomic motivation in that I want to understand the developments in general economic theory that have eventually left us with the microfoundations of macroeconomics that were in force in the 1980s and 1990s. As I see it, the evolution of macroeconomics in the twentieth century has to a large extent been driven by a shift in the understanding of what would constitute appropriate microfoundations. This shift has occurred in several stages which, taken together, have wrought a ‘great transformation’ of neoclassical economics.

It is perhaps best to make clear from the outset that I am not referring to the mathematization of neoclassical economics, since economists of an Austrian persuasion often blame that for what they consider wrong with economics, and since the Stockholm School was at least skeptical about the usefulness of mathematical formalisms.1 But it is not the formalization of economic theory per se or the evolution of successive formalisms that are at stake. It is our understanding of what even the most elemental formalism means that has changed. If there is a methodological lesson in the story that I will try to tell, it is not that we should refrain from formalizing economic theory but simply that being ‘rigorous’ in this particular way has not prevented a very drastic shift in how economists understand the core of neoclassical economics.

I will not be able to trace all the stages in the ‘great transformation’ that I am talking about. Nor can I claim that ‘reasons of space’ are my only handicap. What follows should be understood as attempting a sweeping generalization to make sense of a long and complex historical process. It will have the deficiencies of all such sweeping generalizations. I must leave it to a later occasion – and most probably to other people – to document who, among earlier economists, it truly fits and to whose thought it does violence.

I will proceed by first describing where we have ended up and then go back and attempt a sketch of where we started from. This should provide a firmer idea of what I mean when I refer to this transformation of understanding. Then, I will attempt to describe some of the stages of the process and to indicate at least how and why the Austrians and the Swedes decided not to ‘go along’ with the majority of our profession.

Turn of the century: modern microfoundations

Optimality at individual and competitive equilibrium at aggregate levels are the hallmarks of modern theory. It is largely the meanings attached to ‘optimality’ or ‘maximization’, to ‘equilibrium’ and to ‘competition’ that will be our concern in what follows. They are context-dependent and the conceptual context has not always been the same as the one in force in recent years. At the end of the century, the common understanding may be summarized as follows.

Individual agent level

- Observed behavior is understood as the exercise of choice.

- Choice is represented formally in terms of constrained optimization.

- For the optimization problem to have a determinate solution, the agent has to know his opportunity set in all its dimensions (for example, all prices, present and future).

- The solution is a plan. For the plan to explain observed behavior, the information defining the agent’s opportunity set must be objectively true. Uncertainty about the future can be present only in the form of objectively known stochastic distributions (also, of course, the agent must be able to calculate the optimum).

Market and system level

- If this behavior description is to apply to all agents, the system must be represented as in equilibrium. If observed actions are to be interpreted as realizations of optimal plans, the state of the system must be such that all plans are consistent with one another.

- If all actions always have to be apprehended as part of objectively optimal plans, ‘disequilibrium’ is a meaningless term and ‘equilibrium’ is a superfluous term.

- In a temporal context, the economy is seen as following an intertemporal equilibrium trajectory, conceptually predetermined by the reconciliation of all individual plans. Agents have to know (the probability distributions of ) future equilibrium prices in order to formulate their optimal plans.

- This means that everyone’s choices have to be reconciled before anyone’s choice can be made. The process by which this reconciliation takes place cannot be described within the context of the model.

- The logical contradiction can be avoided by assuming rational expectations, that is, it is supposed that past experience enables agents accurately to predict the stochastic distributions of future prices. The learning whereby agents distill rational expectations from experience cannot be described within the context of the model.

- Further experience is worthless to agents. Shocks to the system never violate the probability distributions that agents take as known. Barreling down the intertemporal equilibrium path, no one learns anything they did not know to begin with.

The present-day intertemporal competitive general equilibrium (ICGE) theory is the end-product of a gradual but profound change in our understanding of what neoclassical economics was all about.

In the past few years, of course, there have been attempts to break out of this conception in macroeconomic models of learning and, in particular, in the theory of repeated games. Perhaps, there is now hope that this most recent focus on issues of learning and expectations formation will in effect revive the older conception of what neoclassical economics once entailed. But here I am concerned with the long transition from this early neoclassical economics to modern ICGE.

Founding fathers

The economists of the British classical school (including Marx) sought to deduce the ‘laws of motion’ of the economy. In spirit, their doctrines were ‘magnificent dynamics’, as Baumol once characterized them. But they lacked, of course, the mathematical tools to formally analyze the dynamics of their system. Presuming (without proof) that the system must go to a point attractor, they were able to analyze its ‘dismal’ stationary state.

The neoclassical system builders similarly conceived of both optima and equilibria as steady-states of individual and collective adaptive processes respectively. This, I would argue, was what they all meant when they referred to the characteristic neoclassical constructions as static theory.

Individual agent level

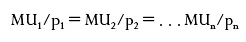

Early marginalist writers might explain, for example, that utility maximization of the consumer would require that the expression

be satisfied. But they did not obtain this condition by formulating and solving a constrained optimization decision problem. Instead, they would demonstrate that if the condition were violated, the consumer ‘could do better’ by very simple rearrangement of his or her purchases. Thus, the optimality conditions for individual agents were understood as rest states of unspecified adaptive processes. As such, they were often referred to as ‘equilibria’ of the household or of the firm.

Market level

Similarly, market equilibria were thought of as the rest-states of interactive processes driven by profit or loss on the margin and by excess demand or supply. Consider, for example, how Keynes in trying to trace the bias in favor of laissez-faire described how economists think. In part, ‘because they have been biased by the traditions of the subject’, he says:

they have begun by assuming a state of affairs where the ideal distribution of productive resources can be brought about through individuals acting independently by the method of trial and error in such a way that those individuals who move in the right direction will destroy by competition those who move in the wrong direction.

(Keynes 1926, section III, italics added)

This is very different, surely, from arguing that the representative agent has correctly solved the economy’s dynamic programming problem defined by the deep parameters of preferences and productivity and that, consequently, the government should leave him or her alone.

The modern theory takes an entirely fantastic notion of human rationality and projects it by construction into an image of how the economy functions. The older neoclassical conception, voiced by Keynes – albeit with critical intent – was that interaction within a framework of market institutions imposed a measure of rationality on market participants.

Competition

The theory of perfect competition started out as an inquiry into the question under what conditions rates of return would be equalized across all industries in the long run stationary state. Again, the analysis concerned the end-state of adaptive processes. As J.B. Clark put it (quoted by E. Lundberg 1930: 13), ‘however stormy may be the ocean, there is an ideal level surface projecting itself through the waves, and the actual surface of the turbulent water fluctuates about it’.

Again, a different conception from the model in which all agents face parametric prices ex ante all the time. Moreover, the older conception was one of a ‘rivalrous process’ (as in Keynes’s quote above), not the measure-theoretic one of independence of actions stemming from everyone’s atomistic insignificance in the market.2

Marshall

It is instructive at this stage to use that other loser in the competition for theoretical influence on twentieth-century theory, Alfred Marshall, as an example and briefly to contrast his mode of theory construction with that of Walras, the retrospective winner.

Walras drew his diagrams with price on the horizontal, quantity on the vertical axis. The first stage in his analysis was finding the agent’s optimal choice of quantity, given the price, qd(p) and qs(p). The second stage was aggregation at given prices and the third, the market clearing equilibrium.3

Marshall drew quantity on the horizontal, price on the vertical axis. He too obeyed mathematical convention because he began by defining the agent’s demand-price and supply-price, given the quantity, pd(q) and ps(q). A demand price is defined as the maximum price a consumer would pay and the supply price as the minimum price a supplier would accept for a given quantity. These, then, are upper and lower boundaries of sets. They are most definitely not the result of some constrained optimization experiment. Marshall does not start from maximization. That is the most important contrast to draw.

Marshallian agents act on simple decision rules. I will refer to them as ‘Marshall’s laws of motion’. Agents are constantly adapting to a changing environment. The basic behavior propositions may be put as follows:

For the consumer – if demand price exceeds market price, increase consumption; in the opposite case, cut back.

For the middleman – if inventory turnover slows down, reduce prices to both customers and suppliers; in the opposite case, raise them.

For the producer – if supply price exceeds the price realized, reduce output; in the opposite case, expand. And, if profits are above normal (given the interest rate), accumulate more productive capital, etc.

These are simple gradient climbing rules. Reliance on them explains, I believe, Marshall’s motto for his Principles: ‘Natura non facit saltum’ and his oft-repeated references to this ‘continuity principle’. While Marshall’s agents obviously do not possess the substantive rationality assumed in modern economics, they may be accorded a measure of procedural rationality in environments where continuity and convexity can both be assumed.

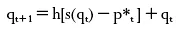

The laws of motion are best thought of as governed by feedback. The producer, for example, obeys a difference equation of the form:

where the expression in brackets measures the difference between his supply price for the quantity he did produce and the price actually received. Note that these values are ex post. Feedback rules are backward-looking, based on the evaluation of immediate past performance.4

Marshall’s starting point, then, is what today we call agent-based modeling: a multitude of heterogeneous agents interacting on the basis of simple behavior rules. But the complex non-linear dynamics which such models normally exhibit neither he nor anyone else in his time could possible handle (imagine all his laws of motion in operation in thousands of markets, at the same time and with different speeds and lags!). He tamed the complex dynamics by assuming (i) a strong ranking of the various adjustment speeds; and (ii) that each of the thus separated processes would converge directly on a point attractor. Thus, his characteristic hierarchy of equilibria – for the market day, the short run, and the long run – has, of course, no counterpart in modern ICGE theory. At each level, Marshall’s concept of equilibrium is constancy of an observable variable as opposed to consistency of the plans of all participants.5

In a previous paper (Leijonhufvud 1998), I have explained how Keynes, working strictly from within this Marshallian tradition, discovered that Marshall’s ‘laws of motion’ did not necessarily converge on a full employment equilibrium but that a more general theory was required. This earlier paper also tries to explain why Marshall and Keynes seem theoretically incompetent to the point of unintelligibility to ‘modern’ readers.

Competition

George Stigler, in his famous essay ‘Perfect Competition, Historically Contemplated’ (1957), noted with some puzzlement that Alfred Marshall did not seem to have contributed at all to the development of the concept of ‘perfect competition’. 6 The reason why he did not stems from the manner in which he built his supply and demand models. The usual interpretation has Marshall obtaining his supply functions from aggregating the maximizing output choices of firms in the now usual way. This would obviously be inconsistent with my assertion that his firms only obey a simple law of motion.

In my interpretation, Marshall obtains his agent-based short-run industry equilibrium first. It is a state where, in the aggregate, the corresponding laws of...