1

Fertility and population policy

An overview

Qiusheng Liang and Che-Fu Lee

China, the most populous nation in the world, reported a population of 1.27 billion in the year 2000. Compared with the population of the United States, 280 million, China had 1 billion more people at the turn of the new millennium. Given 6 billion people over the whole world, Chinese represented a little more than one-fifth of the human race on earth. In late 1979, when the Chinese Government launched an ambitious one-child-percouple population policy, the target was to limit the population of the country within 1.2 billion by the end of the twentieth century. To implement the “one-child” policy the government devised various “carrot and stick” measures to reward couples who pledged to have no more than one child and to penalize those who exceeded the one-child limitation.

Anecdotal reports of forced abortions by local officials who were overzealous in meeting reproductive quotas produced international uproars over human rights violations and calls for sanctioning foreign aid to China’s family planning programs. Many were left with the impression that China had only one population policy, that is, a policy permitting only one child per couple. This fragmented picture of China’s attempts to control its population problem tended to obscure the historical processes of social construction of population growth and efforts to control it in the context of broader development strategies.

This chapter revisits the process of the formation of the Chinese government’s population policies over the past half-century. The primary aim, through a systematic review of the evolving policies over a period of five decades, is to provide a comprehensive picture of the dynamics between policy decisions and their implementation at different points in time since the 1950s.

Developments of population policy in the context of political economy, which are discussed here in some detail, can be demarcated into three stages over the past 50 years: (1) the harbinger of population planning in the 1950s, (2) the chaotic decade of the 1960s and the establishment of the birth-control institution in the 1970s, and (3) a policy experiment followed by a decentralization since the early 1980s.

These policy reviews will serve to frame the discussions of China’s current fertility by showing and discussing year-to-year baseline fertility data for the country since the early 1950s. It will be shown how the “on-again and off-again” fertility control policies of the 1950s and 1960s interacted with non-fertility-related policies and ideologies to keep fertility rates high, especially in the rural areas. The discussions in this chapter will provide an important perspective for the more contemporary analyses of fertility that follow in later chapters of this book (also see Poston and Glover’s Chapter 12 in this book for more discussion).

The 1950s—harbinger of population planning

The Korean war (1950–1953) delayed China’s post-civil-war reconstruction for a few years after the establishment of the new People’s Republic in 1949. On July 1, 1953, China conducted for the first time a national census of its population. The census was required for the preparation of the official First Five-Year Plan and for the apportioning of political representation, the same political purpose for which the United States took its first census in 1790 (Baumle and Poston 2004). The first Plenary Congress of the People was held in 1954. The results of the first population census revealed that China had a total population of 602 million in 1953, a figure that was one-third larger than 450 million, the number commonly believed to be the size of the population in China at that time. Many concerned scholars and government officials, especially those involved with the drafting of the First Five-year Plan, were alarmed by the unexpectedly large number of people that they had to deal with.

The first communication at the upper echelon of the ruling party pertaining to the issue of population may be traced to Deng Xiaoping, the late supreme leader and architect of China’s economic reform from the late 1970s to the 1990s. He was then the Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In his letter (1954) responding to Madam Zhou Enlai (Mr Zhou was the Premier), he stated, “I think it is necessary and beneficial to promote effectively the use of contraception” (Ca et al. 1999:112–113). At the first meeting of the People’s Congress in 1954, a delegate and a noted scholar in China, Shao Lize proposed, “in our country, we may set aside the issue of abortion, but health knowledge about contraception must be propagated. In addition, practical guides and necessary means and material supplies of contraception must be provided” (People’s Daily 1954). Apparently the top leaders were concerned about population pressure, and this was echoed in the public forum. Shao subsequently published a pamphlet entitled, “Basic Knowledge Regarding the Propagation of Contraception,” and continued to write a series of related articles in the public media. Shao would become the first person in the history of the new Republic to openly advocate the practice of family planning or birth control (Ca et al. 1999:113).

Under the leadership of President Liu Shaoqi, a meeting was called at the ministry level in December 1954, to gather inputs on family planning from various government offices. At that meeting, Liu pronounced the support of the Party for planned fertility. In 1955, the Party’s Central Committee approved a report submitted by the Ministry of Health, in which it was said that

regulation of birth is of concern with the living of people’s lives. It is an important policy matter. Given the conditions at this point of our history, for the benefits of the nation, family, and future generations, the Party supports appropriate regulation of births. The Party Secretariats at all levels of government (except in the autonomous regions of the ethnic minorities) must work with the masses to spread this policy of the Party.

(She 1988:120-121)

This became the first official document known as “the Directive on the Problem of Population Control.” This policy decision was then followed by the organization of a leading team for Planned Births, headed by Chen Muhua, who later became the first female vice-premier. Thereupon, the first official policy on population was announced, and the first government office in charge of implementing population policy was born.

In subsequent years, there were other reiterations of the need for population control in relation to economic development. For example, an official document on agricultural development distributed in 1957 included population control as an intrinsic component of the policy. On the other hand, beginning with the 1955 “Directive” followed by other government initiatives in population control, a heated debate was unfolding in academic circles on the pros and cons of the perception of the so-called “population problem.” In the year 1957 alone, it is estimated that more than eighty scholars of all disciplines engaged themselves in writing hundreds of articles on this debate. The most memorable was by an economist and a prominent intellectual, Ma Yinchu, the then president of Beijing University. He treaded a thin line between Marxian ideology and Malthusian theory by publishing a booklet called, “The New Population Theory” (Ma 1997). His major argument was to negate the Marxist doctrine that a socialist society could not have a population problem. He maintained that in a socialist planned economy, population reproduction must be an integral part of the planning. The opposite camp, characterizing themselves as orthodox Marxists, came forth immediately to accuse Ma of adopting bourgeoisie Malthusian population theory. They claimed that the Malthusian view of the population problem blamed the victims, or the oppressed class, for the problem generated by a capitalist system, and hence was antithetical to Marxist doctrine. The misfortune of Ma’s new population theory was, ironically, aggravated by the Great Leap Forward that Chairman Mao launched in 1958 in the midst of the Party’s internal power struggle, an Anti-Rightist political movement. Mao led this political movement to eradicate the socalled capitalist revisionists within the Party. Under fire from this political movement, Professor Ma was labeled as a political rightist and in 1960 was forced to resign the presidency of the most prestigious university in China. The discussions of the population problem and ways to deal with it were muted not only by political pressures but by the economic calamity during the years 1959–1962.

The 1960s—the haunting concern of population in a chaotic decade

If the idea of a planned population and regulated reproduction dawned on the horizon of China in the 1950s, its debate and controversy were limited to the elite circle of the Party leaders and concerned academicians. For the general masses, controlling the number of births contradicted the age-old cultural tradition which deemed a large family as a blessing of good fortune. To the Marxist ideologues, this was antithetical to the building of a Utopian socialist society. Aside from cultural and ideological resistance, the Chinese economy and medical technology in the 1950s were not equipped with a public health system capable of implementing a policy of birth control. Even if the camp advocating control of population growth were to prevail, there was no realistic means to provide the public with the necessary knowledge and effective means of contraception on any scale.

As if adding salt to the wound of the idea of population policy, there was an economic calamity caused by misguided policy and aggravated by radical natural disasters in 1959– 1961. During that period, China experienced a sharp decline in the birth rate together with an unprecedented spike in the death rate. An estimated 30 million or more deaths from starvation or diseases related to under-nourishment occurred during the turn of the decade of the 1960s. In this period, China actually witnessed a negative rate of population growth. Obviously, this historical accident or incident did not help in resolving the paradox of population control in China.

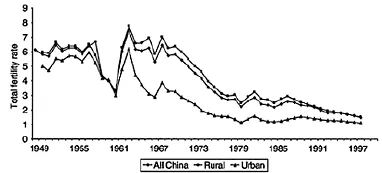

Immediately following the years of the economic fiasco, a “baby boom” occurred, beginning in 1962. During the years 1962–1966, the crude birth rate hovered at around 40 per thousand, representing total fertility rates between 5 and 7 (see Chapter 12 by Poston and Glover in this book for more discussion). The return to traditional high-level uncontrolled fertility was especially true in the rural areas. The total fertility rate was as high as 6 and 7 during most of the 1960s (Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1). The rise in fertility was due mainly to compensatory births delayed during the prior bad years and a recovery of the normal rate of marriage. The demographic impact of this baby boom in the early 1960s would have an echo in the 1980s, as will be discussed in a later section.

Alarmed by the bumper baby crop, the central government returned to the consideration of population control. In 1962, the State Council, the government central executive office, announced a new “Directive.” This time, it was to “seriously” confront the problem of planned reproduction. It commanded the government at all levels not only to promote birth control but also to review the results of its birth-control campaign. To clear up any ideological ambivalence, the new policy document pronounced that planned reproduction was necessary for the construction of a socialist society and was in no way to be confused with reactionary Malthusian thoughts.

The seriousness of this official installation of a population policy was indicated by the institution of a Committee on Planned Births at the central government, and similar administrations in charge of family planning at all subordinate levels down to the local authorities. Government health departments and hospitals began to conduct medical research in contraceptive devices, induced abortion, and sterilization. In addition to the dissemination of contraceptive knowledge, the public health agencies provided contraceptives free of charge. Health workers were recruited for training in order to meet the expanded need for birth control. Finally, the central government set a goal to reduce the population growth to 1 percent or less by the end of the twentieth century, and each of the provinces and municipalities was required to project short- and long-term targets for the birth-control campaign. Hebei province, for instance, in its 1963 “ten-year plan of fertility control,” aimed at a reduction of its crude birth rate to 13 per thousand by 1975; and the Shanghai municipality proposed to decrease its birth rate to 15 per thousand by the year 1967.

Figure 1.1 Total fertility rate (average number of children per woman) for urban and rural places and all China, 1949–1999.

Source: Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Population, birth, and death rates of China, 1949–2000

It was unclear whether these targets of fertility control were supported by any scientific demographic analysis. It was undoubtedly, however, advancement from a stage merely advocating a planned reproduction by the government to another at which the government engages actively in the implementation of birth control. This policy imprint on the precipitous decline during the years 1962–1966 was visible in terms of the period’s total fertility rate (TFR), especially in urbanized areas, as shown in Figure 1.1 in which the rural and urban TFRs are displayed separately.

Led by Shanghai, a campaign slogan, “one is not too few, two, just right, and three, too many” (Ca et al. 1999:157–158), was spread quickly throughout the nation. And the effective measure to achieve a small family size was put in three words, “wan, xi, shao,” or “late, sparse, and few.” “Late” referred to a delay in marriage and the first birth to a later age, “Sparse” was to space the birth interval by 4–5 years, and “few” to limit the number of births to 2 or no more than 3 per couple. To the extent that urban areas and the rural regions in the vicinity of major cities were regimented into work-unit organizations under a socialist system, the planned-birth policy was effectively carried out. The neighborhood committee in the city and production brigade in the countryside were formed as the grass-roots unit in which a women’s association was put in charge of regulating the childbearing behavior of all families in their jurisdiction. Technically, more than a dozen contraceptive paraphernalia were distributed free of charge by these local offices. There were clinics providing sterilization without charging a fee, and the patients were given leave from work with pay.

The Great Cultural Revolution of 1966 in which Chairman Mao mobilized the masses to eradicate his political foes within the Party, brought the administrative system literally to a halt. The government’s role in the birth-control campaign dissolved quickly and was not revived until 1970. The demographic mark of this political turmoil in the late 1960s was a spike in the TFR in both the urban and rural areas (see Figure 1.1).

The Cultural Revolution was not ended politically until the arrest in 1976 of the socalled “gang of four” led by Madam Mao, a group allegedly plotting to usurp the control of the Party central power. Premier Zhou Enlai, who oversaw the economic deterioration while handling a difficult act of balancing the political struggles, was determined to put China’s economic house in order. In 1970 he assembled the various ministries under his command to plan an economic revival. He addressed the issue of planned births and criticized the top officials, saying that “planned population reproduction is not limited to the jurisdiction of the health department, it is an integral part of overall planning. If you cannot plan for population growth, it is futile to talk about national planning” (Sun 1990:158). In 1971 the State Council issued a referendum on the nationwide campaign of fertility planning. The short-lived movement of birth control in the early 1960s was thereby resuscitated and even more vigorously enforced. This time the reinstitution of a population policy was also blessed by Chairman Mao’s endorsement. In approving a government document in 1974 in his later years, he uttered that “population must be controlled by all means” (Ca et al. 1999:166). At that time Mao was still a god-like supreme center of power in China. With his stature, he commanded the eager following of the planning policy not only by party officials but also widely among the masses, especially the city folks who were mostly employed by the state.

Unlike the one-child policy in the 1980s, which had compulsory penalties for violators, the vigorous administrative means of watching closely over women of reproductive ages and regulating their birth behavior in the 1970s was leaning more toward the prevention of ex...