eBook - ePub

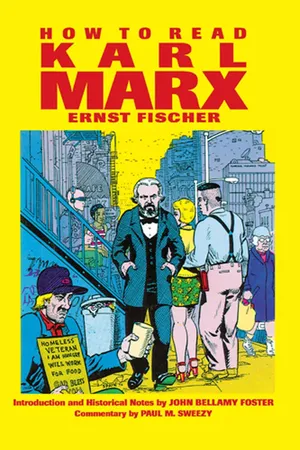

How To Read Karl Marx

Ernst Fischer, Franz Marek

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 224 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

How To Read Karl Marx

Ernst Fischer, Franz Marek

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

A brief, clear, and faithful exposition of Marx's major premises, with particular attention to historical context.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es How To Read Karl Marx un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a How To Read Karl Marx de Ernst Fischer, Franz Marek en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Política y relaciones internacionales y Ideologías políticas. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Ideologías políticas1

THE DREAM OF THE WHOLE MAN

Marx’s entire lifework was motivated by “the dream of a whole man,” of an integrated human being—the basis of an integrated humanity—in which the humanity that resides within each individual would be realized. The realization of this inner potential of human beings, which for Marx was the same as the development of human freedom, required the transcendence of the alienation of human beings from each other and themselves. It required the liberation of humanity from the pursuit of narrow economic ends and the opening up of wider realms of creativity. This humanism in Marx’s vision, Fischer demonstrates, was apparent in both Marx’s treatment of religion and in his dialectical method.—JBF

Marx’s thought underwent many variations in the course of his life, but what had served as his starting point remained intact: the possibility of the whole, the total man.

Since the triumph of the industrial revolution and of the capitalist method of production at the turn of the eighteenth century, the fragmentation of man through the division of labor, mechanization, exploitation, and commerce had become the fundamental European experience. The longing for unity with one’s own self, with one’s kind, and with nature, from which man had become alienated, was common to all those who entertained humanist feelings and ideas.

In their romantic revolt against a world which turned everything into a commodity and degraded man to the status of an object, the poets and philosophers of the iron age complained that man had become a fragment of his own self, had been overpowered by his own works, had fallen away from himself.

Enjoyment was divorced from labor, the means from the end, the effort from the reward. Everlastingly chained to a single little fragment of the Whole, man himself develops into nothing but a fragment; everlastingly in his ear the monotonous sound of the wheel that he turns, he never develops the harmony of his being, and instead of putting the stamp of humanity upon his own nature, he becomes nothing more than the imprint of his occupation or of his specialized knowledge. (Friedrich Schiller, On the Aesthetic Education of Man, in a Series of Letters, trans., Elizabeth M. Wilkinson and L.A. Willoughby [Oxford, 1967: Clarendon Press], sixth letter, p. 35.)

The age of turbulent development of technology and industry, of greed and the mercantile spirit, of capital and of proletarian misery, of revolutionary hopes and their disappointment by post-revolutionary reality, became the age of romantic protest against the complacent bourgeoisie. Both the aristocratic and the plebeian opponents of the bourgeois world joined in that protest; both condemned the dehumanization of man by the progressive division of labor whose extreme consequence, at one end of society, was ever-increasing wealth and, at the other, ever-increasing material and spiritual wretchedness. But, as time went on, a certain differentiation took place within the romantic movement: some looked to the past as the only mainspring of salvation and imagined it as a time of human unity and dignity; others turned towards the future, dreaming of the resurgence of the whole man in a coming realm of freedom, abundance, and humanity.

The political revolution in America and France had proclaimed man’s right to liberty—the “free personality.” The contrast between such proclamations and the reality which followed was painful to many. Man in bourgeois society had indeed become an individual—not in community with others, but in harsh competition against them. “Liberty as a right of man,” wrote the young Marx, “is not founded upon the relations between man and man, but rather upon the separation of man from man.”1

None of the supposed rights of man, therefore, go beyond the egoistic man, man as he is, as a member of civil society; that is, an individual separated from the community, withdrawn into himself, wholly preoccupied with his private interest and acting in accordance with his private caprice.2

The problem therefore was to turn men, reduced to an empty individuality, away from purely private interests and preoccupations, to unite the individual with a community based on the freedom of all rather than on the dominance of a few.

The notes Marx made for his doctoral thesis at Berlin University at the age of twenty-one do not as yet contain any mention of the class struggle, of the proletariat and revolution, of the “realm of freedom” in a classless society without rulers. But we do find, in the sixth notebook, the following sentence on the subjectivism, the fundamental self-centeredness of the epicurean and stoical philosophies: “Thus, when the universal sun has set, does the moth seek the lamp-light of privacy!” And even earlier, in the third notebook: “He who no longer finds pleasure in building the whole world with his own forces, in being a world-creator instead of revolving forever inside his own skin, on him the Spirit has spoken its anathema.” And finally, in the seventh notebook: “Least of all are we entitled to assume, on the strength of authority and good faith, that a philosophy is a philosophy, even if the authority is that of a whole nation and the faith is that of centuries.”3

The “universal sun” for Marx was the individual’s commitment to a common goal, his participation in the res publica, the public cause, the fact that his actions and ideas could transcend narrow private interest—in other words, something like Athenian democracy or the Roman republic before the dictatorship of the Caesars. Marx refused to “revolve forever inside his own skin”: he wanted to be a “world-creator,” making the world intellectually his own and eventually contributing to its material transformation. The desire for a new social dawn, for a “universal” sun that would make the lamplight of privacy appear dull by comparison, is unmistakable. But equally there is the stirring of a critical mind unprepared to accept authority and good faith as proof of the truth of any philosophy, doctrine, or system. Marx at twenty-one was already eager to forge ahead towards a new universality, to be the creator of a new world—without forgoing the right to submit everything already in existence, or coming into existence, to critical re-examination.

In Berlin, where Marx read jurisprudence, philosophy, and history, the dominant spirit was that of Hegel, who exercised a great fascination over the younger scholars and thinkers. In his gigantic philosophical opus, which was both the crowning point and the negation of romanticism, Hegel saw the world spirit in world history traverse every successive form of alienation—of the falling away from the self—and simultaneously also of the return to the self, of reconciliation, thus progressing from an unconscious unity with the self to a conscious one. Hegel’s difficult philosophy was a manifestation of the contradictory dynamic of his age—the notion of development, the dream of a realm of freedom and plenitude, of a reality that has become conscious of itself.

Marx as a young man at first rejected Hegel, but was soon captivated by the great philosopher and his dialectic. He was to remain faithful to the dialectic—the inner contradiction within the nature of thought and of all things, the recognition that nothing can be understood in isolation or as a rectilinear sequence of cause and effect, but only as the multiple interaction of all factors and as being in conflict with itself: that everything, as it comes into being, produces its own negation and tends to progress towards the negation of the negation. But he went far beyond Hegel in the consequences he drew.

As editor of the liberal Rheinische Zeitung in 1842 to 1843, Marx with his radical-democratic views became a thorn in the flesh of the Germany of the 1840s and had to move to Paris. Writing in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher in 1844, he described and castigated the conditions in Germany from which he had escaped in the following words:

German history, indeed, prides itself upon a development which no other nation had previously accomplished, or will ever imitate in the historical sphere. We have shared in the restorations of modern nations without ever sharing in their revolutions. We have been restored, first because other nations have dared to make revolutions, and secondly because other nations have suffered counter-revolutions; in the first case because our masters were afraid, and in the second case because they were not afraid. Led by our shepherds, we have only once kept company with liberty and that was on the day of its interment.4

In Paris Marx met the young Frederick Engels, the son of a manufacturer from the Rhineland, then working in London. Through him he not only gained an insight into the social conditions prevailing in the most advanced industrial country of the time, but, above all, Engels became a friend such as there have been only few in history. During the collaboration which followed and which was unparalleled in its closeness and in the length of its duration, Engels recognized—without a trace of envy—the surpassing genius of his occasionally somewhat difficult friend, and became his devoted helper not only in intellectual, scientific, and political matters but also, over and over again, in private life. Engels’s philosophical contribution to Marxism can be contested: but the productive and enduring friendship which united Marx and Engels stands high above all criticism.

What Marx came to know in Paris was the proletariat.

He saw the wretched figure of the proletarian as the quintessence of dehumanization, the extreme of everything the Romantics felt to be the denial and mockery of the nature of man. But precisely in this extreme negation Marx saw the hope of overcoming it. He believed that the proletariat was forced by its very poverty to liberate itself from inhuman conditions by overturning those conditions at their base, and that, by liberating itself, it would become the liberator of mankind.

There is an extraordinary poignancy about the way Marx described the negation of man as found in the proletarian of his time.

Labor certainly produces marvels for the rich, but it produces privation for the worker. It produces palaces, but hovels for the worker. It produces beauty, but deformity for the worker. It replaces labor by machinery, but it casts some of the workers back into a barbarous kind of work and turns the others into machines. It produces intelligence, but also stupidity and cretinism for the workers.5

The proletarian in his work does not fulfil himself but denies himself,

has a feeling of misery rather than well-being, does not develop freely his mental and physical energies but is physically exhausted and mentally debased. The worker therefore feels himself at home only during his leisure time, whereas at work he feels homeless.6

Marx was, of course, a master of needle-sharp comment, but many contemporary records prove that he was not exaggerating when he spoke of the wretchedness of the proletarian. The Young Hegelians, the great philosopher’s radical disciples, expected atheism to liberate man by bringing his spirit back from the beyond into the real world. Marx’s view was more profound; the criticism of religion was for him “the premise of all criticism,” but he was aware of the need for liberation from material as well as spiritual bondage, and he saw religion both as “the expression of real misery” and as the “protest against real misery.” “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the sentiment of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”7 As is so often the case, not many people are aware of what Marx really said in this context: the quotation is usually twisted to imply that religion was opium for the people, that is to say a narcotic given the people by outside forces, while the preceding sentence is ignored.

Atheism, as a denial of this unreality [the unreality of man and nature], is no longer meaningful, for atheism is a negation of God and seeks to assert by this negation the existence of man. Socialism no longer requires such a roundabout method; it begins from the theoretical and practical sense perception of man and nature as essential beings. It is positive human self-consciousness, no longer a self-consciousness attained through the negation of religion; just as the real life of man is positive and no longer attained through the negation of private property, through communism.… Communism is the necessary form and the dynamic principle of the immediate future, but communism is not itself the goal of human development, the form of human society.8

We can see that religion, atheism, and communism were, for Marx, stages or features of development rather than its goal. The goal was positive humanism, the real life of man. The existence of the proletariat was the most striking contradiction of such a life; but “the ruptured reality of industry” did not manifest itself in the proletariat alone. Scientific analysis of capitalist industry confirmed a hundred times over what Schiller had only apprehended: that “enjoyment was divorced from labor, the means from the end, the effort from the reward”; that the proletarian was only the most extreme expression of the fragmentary, disconnected, rent nature of the world of machines, profits, and poverty. As the negation became more clearly pronounced, so the thing it negated became clearer too: the unrealized image of man.

The starting point of religion is God. Hegel’s starting point was the State. Marx’s was Man.

In the Critique of Hegel’s State Law Marx wrote:

Hegel proceeds from the State and makes man the State subjectified; democracy proceeds from man and makes the State man objectified….

Man does not exist for law’s sake, law exists for man’s sake; it is human existence, whereas [for] the others man is legal existence. That is the fundamental difference of democracy.9

The decisive thing for Marx is not simply “the universal,” a system as an end in itself, but man—concrete, real, individual man. The object of his thinking, of all his efforts, is the whole man, the reality of man, positive humanism.

Man needs the community in order to develop into a free individual. “In the previous substitutes for the community, in the State, etc., personal freedom has existed only for the individuals who developed within the relationships of this ruling class, and only in so far as they were individuals of the class.” Individuals who behave as though they were independent are in actual fact conditioned not only by the whole of social development—by language, tradition, upbringing, etc.—but also by their class, estate, or profession. Their personality is conditioned and determined by quite definite class relationships. Although the mutual relationship between them is a relationship between persons, it is above all one between “social character masks”—not as specific individuals, but as standardized “average individuals.” Marx hoped and believed that with the “community of revolutionary proletarians” it would be just the reverse: individuals would participate in it as individuals. Marx saw communism, and, with it, common control over the conditions which “were previously abandoned to chance and had won an independent existence over against the separate individuals just because of their separation as individuals,”10 not as a system of classes and castes—of “social character masks”—but as a free association of individual men.

Between the individual and society there is an interaction:

As society itself produces man as man, so it is produced by him.… The human significance of nature only exists for social man, because only in this case is nature a bond with other men, the basis of his existence for others and of their existence for him. Only then is nature the basis of his own human experience and a vital element of human reality.11

Although our time of scientific and technical revolution calls for an ever-increasing measure of teamwork, the work of a scholar, a writer, or an artist is not directly bound up with other people and may actually suffer from direct social intervention. Yet su...