![]()

PART I

Introduction

![]()

ONE

How Civil Wars End: Questions and Methods

Roy Licklider

Civil violence may be rare or common, but it is always in some sense extraordinary, a challenge to one of the basic assumptions of civil normality.

—(Rule 1988, 2)

Our world is filled with violence of every sort, from the daily random killings of children by stray gunfire to mass murders and large-scale wars in places we can hardly locate on maps. But even in this environment of violence, civil war retains a particular horror.

Perhaps this is because of the peculiar intensity of many such conflicts. We say that family fights are the worst because the degree of feeling is so deep, that you really have to know someone to hate them. James Rosenau (1964, 73) argues that the intensity stems from the depth of prewar ties which have been destroyed. Certainly the degree of personal commitment, with its resulting heroism and savagery, in societies like Ulster, Lebanon, Cambodia, and Angola is hard for outsiders to comprehend.

At a deeper level, civil war reveals the fragility of our own social peace. Could our own society ever degenerate into the anarchy of Lebanon? The vision of people who would otherwise be living peacefully together deliberately killing one another retains its power to shock. The people in Ulster, for example, seem much like those of any Western industrial country; if they are unable to maintain social peace, what does that say about us and our own future? Any stable society can be seen as a suspended civil war, and the troubles of others remind us of our own susceptibility to the condition. After all, the United States fought one of the bloodiest civil conflicts in history little more than a century ago. We know that it can happen here because it has.

We also worry about civil wars because, in this increasingly interdependent world, they are not private quarrels; they attract outside involvement and may escalate into international conflicts which will involve us directly. Some of the most intense Cold War confrontations, for example, resulted from interventions in civil wars in the Third World in places like Korea, the Middle East, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. Nor is this simply a modern phenomenon; after all, the French Revolution ignited a world war. Thus the end of the Cold War is unlikely to end this spiraling cycle of involvement and violence; indeed, if anything, the likely outbreak of new civil wars in the former Soviet bloc may increase it. Enlightened self-interest demands that we learn how such conflicts begin and how they may best be ended.

It is particularly hard to visualize how civil wars can end. Ending international war is hard enough, but at least there the opponents will presumably eventually retreat to their own territories (wars of conquest have been rare since 1945). But in civil wars the members of the two sides must live side by side and work together in a common government to make the country work. How can this be done?

Sustained wars produce hatred which does not end with the conflict. After half a century, American veterans were outraged at the idea of including some Japanese veterans in the fiftieth anniversary ceremony of the attack on Pearl Harbor. How do groups of people who have been killing one another with considerable enthusiasm and success come together to form a common government? How can you work together, politically and economically, with the people who killed your parents, your children, your friends or lovers? On the surface it seems impossible, even grotesque.

But in fact we know that it happens all the time. Fred Ikle’s apt title Every War Must End applies to civil wars as well. The violence stemming from religious differences within Europe several centuries ago has ended. England is no longer criss-crossed by warring armies representing York and Lancaster or King and Parliament. The French no longer kill one another over the divine right of kings. Americans seem agreed to be independent of English rule and that the South should not secede. Argentines seem reconciled to living in a single state rather than several. The ideologies of the Spanish Civil War now seem irrelevant, and even the separatist issues there are not being resolved by mass violence. More recently, two separatist wars in South Asia have produced the independent states of Pakistan and Bangladesh. Conflict in the area remains likely, but no one seems interested in extinguishing the two successor states. Nigeria experienced one of the most brutal civil wars of our time, but the violence ended 20 years ago, and while the country is politically unstable, the divisions are not the same as in the civil war. Other cases can be found (including those in this volume). Somehow new societies were constructed after the war, involving most of the people who had fought on opposite sides.

But how did this happen? We know very little about the processes involved. How are armed societies disarmed? Do outside interventions (military assistance to one side or both, offers of mediation, humanitarian aid) help or hinder a settlement? Are lasting solutions more likely before or after total military victory by one side? Does it make a difference whether the underlying issues are ethnic divisions or political differences, whether the goal has been separation from the state or conquest of the state apparatus? Is peace more likely when both sides are strong or when they are divided? Can the central issues be compromised in the initial settlement, or does a draconian solution work best in the long run? Why do some “solutions” last and others collapse? Most importantly, what can we learn from these experiences about the circumstances under which civil societies may be constructed from civil violence? That is the central focus of this book.

How Important Is Civil War?

Jimmy Carter recently said that of the 116 wars since World War II, all but the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait were civil wars. (Jack Levy notes that Saddam Hussein would disagree, viewing Kuwait as part of Iraq.) Statements like these depend on the definitions being used, but the systematic studies of recent wars demonstrate the importance of civil war, no matter how it is defined. In 1973 Robert Randle asserted that “since the first use of the atomic bomb against Japan, there have been at least 18 wars between states and 55 civil wars” (Randle 1973, x). The seminal Correlates of War project identified, between 1945 and 1980, 43 civil wars, 12 international wars, and 18 extrasystemic (colonial and imperial) wars (Small and Singer 1982, 56–57, 80, and 222). Paul Pillar (1983, 21) lists 16 civil, 14 international, and 9 extrasystemic wars after 1945. Gantzel and Meyer-Stamer (1986; cited in Wallensteen 1991, 215) developed a list of 31 wars going on in 1984; 26 of them were classified as internal. Hugh Miall (1992, 115–116 and 124) constructed a set of about 350 conflicts between 1945 and 1985. From this he worked with a subset of 81 and found 6 international conflicts with major violence as compared to 28 civil or civil/international ones. Ruth Sivard (1988) counted 24 wars being fought in 1987, 22 of which were civil wars or wars of secession. The common ground of these studies is that civil violence is a major phenomenon in the current world.

It therefore seems unreasonable to omit such struggles from theories of conflict and violence. Nonetheless they have received much less attention than interstate conflicts, for reasons that are not altogether clear. Practitioners tend to focus on individual civil struggles rather than looking for patterns; few people, after all, are likely to have had direct experience in resolving more than one. Academics might be expected to take a wider view, but they are sometimes restrained by the sociology of their disciplines. Among political scientists, for example, interstate war is part of the field of international politics, while the study of internal wars is often included in another field, comparative politics. Perhaps as a result, the very substantial amount of research on interstate war has had little impact on the study of civil wars. Historians tend to focus on individual conflicts rather than generalizations about many such wars, and neither discipline has much contact with sociology, which alone among the disciplines has produced a substantial literature on the topic.

Indeed, the termination of civil violence is relevant to a wide variety of intellectual fields of study.

The ‘problem of order’ … is often alleged to be the most fundamental on the agenda of social science.… Most of the major currents in social and political thought since Hobbes’s time have contributed something to the debate on the origins of civil violence. Most of the key methodologies current among social scientists today have served as vehicles for arguments on the subject. As much as any other relatively delimited issue, it offers a microcosm of social science thinking. (Rule 1988, xi and 3)

Conflict resolution has focused primarily on less violent disputes within states and interstate wars, omitting civil wars; the recent interest in what are often called protracted or intractable conflicts (Kriesberg, Northrup, and Thorson 1989) has begun to compensate for this and offers one way to bring these two different areas together. The immense literature on revolution has focused primarily on the origins of such conflicts, with very little concern given the process by which they end and produce major social impacts. The recent concern with ethnic groups often encourages us to look at conflicts among them, some of which escalate into violence; it is perhaps more important to determine how they can coexist in the same state relatively peacefully, especially after they have been killing one another. The failure to end such conflict may sometimes produce genocide and policide, the study of which has developed into a specialty area of its own (Kuper 1981; Walliman and Dobkowski 1987). We cannot seriously study political and economic development without looking at how civil wars are ended. The list goes on.

Analysis of civil violence has focused on explaining its origins (a prominent exception is Gurr 1988.) It is particularly infuriating that two of the best books on internal war (Eckstein 1964 and Rule 1988) both explicitly note the importance of studying how such conflicts end and then proceed to ignore the topic. Of course this is also true of interstate wars, whose causes have been extensively studied while the equally interesting question of how and why they end has been, for the most part, curiously neglected.

Little has changed in the quarter century since Harry Eckstein lamented:

No questions about internal war have been more thoroughly neglected by social scientists, in any generation, than these long-run ones.… This neglect is most serious in what may well be the most crucial practical question that can be asked about internal war … : How is it possible to re-establish truly legitimate authority after a society has been rent by a revolutionary convulsion? How does one go from a “politics of aspiration” to a settled civic order? It is extremely common for internal war to grow into an institutional pattern of political competition by force, less common for a truly “civil” society to emerge from a major internal war, except in the very long run. What then are the circumstances under which the self-renewing aspects of internal war become, or may become, muted? (Eckstein 1964, 28-29; cf. Modelski 1964b, 126)

But does it make any sense to look at civil wars separately from large-scale conflict in general? After all, if even the experts can’t agree on the distinctions between civil and interstate wars, why should we expect them to end differently? We don’t really know, but there is good theoretical reason to expect that civil wars may be resolved differently than wars among states.

In conflicts that are predominantly civil wars … outcomes intermediate between victory and defeat are difficult to construct. If partition is not a feasible outcome because the belligerents are not geographically separable, one side has to get all, or nearly so, since there cannot be two governments ruling over one country, and since the passions aroused and the political cleavages opened render a sharing of power unworkable. (Ikle 1971, 95)

The civil war that ensues will be a violent military struggle between two societies so committed that victory for one means extinction for the other. Thus a society organized as either envisions would be incompatible with the continued existence of the other; the alternative becomes Victory or Death, God or the Devil, Freedom or Slavery. Once the battle has been joined, the war is total and the outcome is seen only as total victory or total defeat. Neither side at any stage can seriously contemplate any alternative to victory except death—if not of the body then of the soul. (Bell 1972, 218; cf. Modelski 1964b, 125-126; Pillar 1983, 24-25)

This general argument is developed eloquently in the next chapter in I. William Zartman’s powerful analysis of the difficulties of ending civil wars based on a large number of current examples.

If this is true, we would expect civil wars to be both more intense and more difficult to resolve than interstate wars. There is some support for both hypotheses. Hugh Miall’s conflict data shows that 15% of international conflicts involved major violence, while a full 68% of civil and civil/international conflicts did (Miall 1992, 124). Paul Pillar’s data (1983, 25) show about two-thirds of interstate wars ending by negotiation as compared to about one-third of civil wars. Using a somewhat modified data set, Stedman (1991, 9) found that, when colonial wars and other “special” cases were eliminated, the civil war figures declined to about 15%.

These data have somewhat ambiguous implications. On the one hand, casualties do seem to be higher and settlements more difficult in civil conflict, suggesting that there may be interesting theoretical differences between the different sorts of violence. On the other hand, while suppression, genocide, or partition are certainly possible, negotiated settlement in civil violence does in fact occur, as seen in the cases of Colombia, Sudan, and Yemen in this volume.

What Is a Civil War and When Does It End?

This line of reasoning also suggests that the conventional definition of a civil war, large-scale violence between two or more groups holding sovereignty within a recognized state, is inadequate. The problem is the notion of recognized state, which is essentially a legal criterion. Using this definition, it’s not clear that, for example, the Palestinian uprising in the territories occupied by Israel is a civil war, since one can view Israel as an occupying force rather than a recognized state in the occupied territories. Similarly, as Robert Mortimer has pointed out, the war in Zimbabwe can be viewed as a colonial struggle, since there was no legitimate government in place before the end of the conflict.

However, Ikle’s argument suggests that the particular intensity of a civil war stems from the nature of the stakes, from the expectation that after the violence, regardless of the results, the participants will have to live together in the state which is being shaped by the conflict. Thus we use the term civil war to mean large-scale violence among geographically contiguous people concerned about possibly having to live with one another in the same political unit after the conflict. In particular it incorporates two different kinds of criteria.

(1) There must be multiple sovereignty, defined by Charles Tilly as the population of an area obeying more than one institution.

They pay taxes, provide men to its armies, feed its functionaries, honor its symbols, give time to its service, or yield other resources despite the prohibitions of a still-existing government they formerly obeyed. (Tilly 1978, 192)

This criterion differentiates civil wars from other types of domestic violence, such as street crime and riots.

(2) In addition, a civil war, by our definition, involves physical violence to people. We have used the operational definitions of the Correlates of War project: (a) 1,000 battle deaths or more per year and (b) effective resistance (either at least two sides must have been organized for violent conflict before the war started or the weaker side must have imposed at least 5% of its own casualties on its opponent), to distinguish between civil wars and political massacres (Small and Singer 1982, 214-215).

As defined, the term civil war thus logically includes wars of conquest, where one group tries to incorporate another into the same state, but very few of them can be found after 1945. (Even the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait remains somewhat debatable, as noted above.) The Palestinian uprising would be included in this definition since Arabs and Jews are likely to cohabit some states, regardless of the outcome. Similarly Zimbabwe becomes a relevant case because the issue of the conflict was the nature of the government which would control the state in which most of the combatants expected to reside.

But what does it mean to say that a civil war ends? It is commonplace, for example, to say that the American civil war has not yet ended, that the struggle between differing cultures in the north and south continues to this day in various ways. Here we distinguish between war and conflict. The distinguishing qualities of war are multiple sovereignties and violence, as set forth above. The underlying conflict which triggered the violence may well continue, but if (1) the violence or (2) the multiple sovereignty ends, the war ends as far as we are concerned.

Research Strategy

When this project began in 1987, these questions represented something of a chicken and egg problem. There were neither applicable theories to test nor case studies which might be used to generate such theory. Moreover, the problem was clearly larger than any single person could handle. The obvious approach was a collaborative and iterative strategy, combining the intimate knowledge of specialists in particular examples with the broader interests of theorists, moving back and forth between cases and theory.

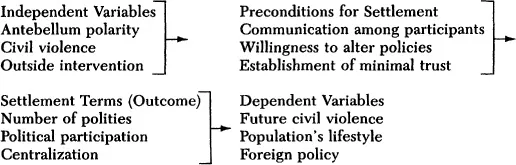

To get started, I sketched out some very tentative ideas about why civil wars might end, including questions and variables which might be relevant (Licklider 1988). This framework (it was far from a theory, since there was no serious discussion of how these variables were related to one another) is summarized in the following diagram:

There were lots of problems with this initial framework, and it was largely abandoned later. However, it did have the advantage of specifying that the reason civil wars end the way they do was interesting, that we were concerned with the consequences of such conflicts on people, states, and the international system, and that the connections between these factors should not be ignored in our research.

In the second phase of the project, this framework served as the basis for a group of comparative case studies prepared by area experts with particular knowledge of the individual conflicts. These cases were to be used to develop and refine the original set of variables inductively, hopefully allowing us to move toward something closer to testable theory about the conditions under which civil wars end.

Clearly case selection was critical. We can all recite litanies of civil wars which seem endless—Ulster, Lebanon, Cambodia, etc. But we seem to know less about those which have ended. Therefore, the cases were deliberately chosen as examples of large-scale civil violence which had ended, at least for a considerable time. They were designed to encourage theory development. Clearly they could not be used to test theory, since they were all “successful” in reducing conflict. Theory testing would require comparable cases in which the violence had not ended (although even within this sample of “successes,” longitudinal comparisons were still possible by asking why a settlement had not been reached earlier).

The cases were chosen from large-scale civil conflicts which had ended, at least for some considerable time and were identified by the Small and Singer (1982) data. We classified a civil war as ended when the level of violence had dropped below the Small-Singer threshold of 1,000 battle deaths per year for at least five years. This criterion produced at least two apparent anomalies among the seven cases. Colombia 1957 was included because violence diminished for several years and, when it was renewed, involved different contestants and issues. The 1972 settlement in Sudan was included because violence declined for over five years, even though the agreement eventually broke down and resulted in renewed conflict with essentially the same participants and issues.

In order to narrow the focus of the study, pre-1940 cases were excluded. This is a conventional strategy, especially in the study of international relations ...