![]()

Langhans W, Geary N (eds): Frontiers in Eating and Weight Regulation.

Forum Nutr. Basel, Karger, 2010, vol 63, pp 9–53

______________________

Overview of the Physiological Control of Eating

Wolfgang Langhans · Nori Geary

Physiology and Behaviour Group, Institute of Food, Nutrition and Health, ETH Zürich, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland

Introduction

Aim

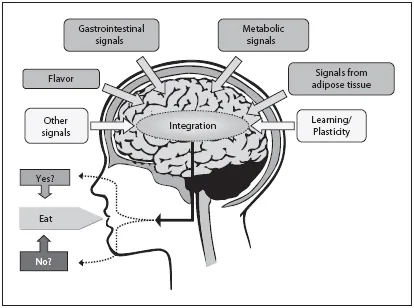

In this chapter we discuss the physiology of eating, with a particular focus on its relevance to the present obesity epidemic. The physiology of eating comprises the functional organization of eating behavior, the types of exteroceptive and interoceptive information that affect eating, the neural and endocrine sensory mechanisms relaying this information to the central nervous system (CNS), and the CNS neural networks that process and integrate this and other information to control eating (fig. 1). We emphasize the role of eating in the regulation of body weight. These topics have taken on new importance with the obesity epidemic. It is well recognized that overeating together with reduced exercise are the proximal causes of obesity. Therefore, better understanding of the physiology of eating and its role in body weight regulation, or dysregulation, should lead to new and hopefully more effective approaches for the therapeutic control of eating in obese persons or persons at special risk for obesity and obesity-related diseases.

The Functional Organization of Eating

Eating in humans and other mammals is functionally organized into discrete meals. Meals are produced by four separable functional processes with at least partially independent underlying neural mechanisms. Although each process includes both behavioral and subjective phenomena, for simplicity we use single names for both aspects. The four processes are: (1) processes related to the initiation of meals (hunger processes); (2) processes related to the evaluation of the food that stimulate or inhibit eating during the meal; this is one aspect of food reward; (3) processes related to inhibitory feedbacks from postingestive food stimuli that act to terminate eating at the end of the meal (satiation), and (4) processes inhibiting eating during the intermeal interval (postprandial satiation). As will become clear, each of these processes is affected both by phasic inputs, for example, inputs related to the secretion of hormones from the gut before, during and after meals, and by tonic inputs, for example, inputs related to the mass of the adipose tissue and, therefore, body weight.

Fig. 1. Schematic of the control of eating. The decision to eat or not eat that is made before each bite or sip is the outcome of central nervous system integration of a variety of peripheral signals, including peripheral neural, hormonal and other humoral signals, information stored in the brain, such as learned effects of previous experience, food expectancies, etc., and with other signals, such as circadian or immune effects, situational context, energetic demands, etc. The schematic is superimposed on a shadow drawing of a midsagittal section of the head, including the skull, brain and spinal column. Reproduced with permission from Langhans et al. [280].

An important implication of the fact that at least partially separate mechanisms control different meal processes is that summary measures of food intake, e.g. g/day, may conflate independent underlying processes. For example, in some situations, meal size and meal frequency change in opposite ways, so that the patterns of spontaneous eating can be different even though total amount eaten is not. A related point is that parts of the overall eating-control neural network with functionally antagonistic effects may operate simultaneously. Thus, eating-inhibitory controls might arise in one part of the network (e.g. homeostatic signals related to metabolic fuel utilization) at the same time as eating-stimulatory controls are activated in other parts of the network (e.g. signals related to orosensory food reward). The existence of such partially autonomous controls may be part of the reason why existing treatments based on pharmacological manipulation of single signaling molecules have not been effective in normalizing disordered eating.

Regarding the subjective phenomena associated with eating, our view, following William James [1], is that the most parsimonious explanation for the richness of eating-related emotional and cognitive experiences is that they evolved as causal agents contributing to the overall control of eating and its orchestration with other biological functions. How conscious processes actually affect neuronal function and behavior is, of course, beyond the scope of available methodologies, although imaging methods now produce at least hints that eating behavior and some of the subjective phenomena associated with eating arise in the same neural networks and are modulated by the state of energy balance. The chapters by Neary and Batterham [2], Kringelbach and Stein [3] and Stice and Dagher [4] touch upon this fascinating topic.

There are levels of organization of eating behavior both above and below the levels of meals. Subordinate to the level of meals is the microstructure of eating, including, for example, analyses of licking, biting, chewing or swallowing food during meals. This level of analysis seems to hold great potential for tracking eating behaviors via the lower motor neurons and central pattern generators that produce the movements of eating back into the higher, more integrative levels of the neural networks for eating. Superordinate levels include the control exerted by biological rhythms, such as circadian and reproductive rhythms, both of which potently affect human eating. The most important superordinate level, however, is the level mediating the regulation of body weight. That is, when adiposity or body weight is perturbed, the organism tends to eat in a way that corrects the error. The physiology of such weight-regulatory influences is a major theme of this book and is introduced in more detail in the next section.

Eating and Homeostasis

Because eating is our only source of metabolic fuel and of a number of essential nutrients, it is an integral part of homeostatic regulation. Myriad studies have demonstrated that both the regulation of metabolic energy supply and the regulation of micronutrient balance powerfully influence how much is eaten and what is eaten. As a consequence, homeostasis is a major conceptual scheme used to understand eating.

Body weight, at least in adulthood, is a relatively accurate surrogate for the state of energy balance over longer periods (i.e. periods during which changes in gut contents, hydration, etc., can be ignored). Over such periods, changes in body weight in adults usually reflect changes in adiposity, i.e. mainly the amount of energy substrate stored as triacylglycerols in the adipose tissue (there is also ectopic storage of triacylglycerols in liver, muscle and other tissues). Thus, longer-term state of energy balance is described by the energy balance equation:

Energy stored = Energy ingested - energy expended.

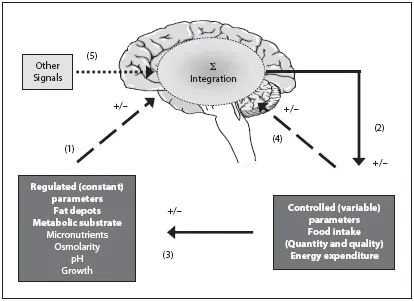

Fig. 2. Schematic of the components of homeostatic regulatory systems involved in the control of eating. Regulated parameters (lower left box) are held relatively constant, in part by changes in controlled or variable parameters (lower right box). The negative feedback control system thought to regulate body adiposity is shown in bold font; other regulated variables controlling eating are shown in normal font. In adiposity regulation: (1) Feedback signals reflecting deviations from the desired value (set point) in the regulated parameter, adiposity, are detected by the brain, (2) causing compensatory changes in eating or energy expenditure, which (3) affect adiposity. In addition, (4) eating produces other feedback signals to the brain that affect the control of meal onset, rate of eating, and meal termination. Finally, (5) other exogenous and endogenous signals outside these feedback loops also affect eating. Modified with permission from Langhans et al. [281].

The relative stability of body weight over longer periods appears possible only if an active regulatory system senses energy stored and, depending on its level, appropriately adjusts energy ingested or energy expended. Figure 2 depicts how this system is believed to function. The brain registers and integrates (Σ) feedback signals which reflect deviations from the desired state (1), and adjusts eating and energy expenditure (the controlled variables) (2), so that the regulated variable, energy stored, is maintained in a relatively narrow envelope (3). The regulation of energy homeostasis and body weight is discussed further in this chapter as well as in the chapter by Hillebrand and Geary [5].

As also shown in figure 2, the feedback signals that are not related to energy homeostasis also affect the controlled variables. These include signals related to the sensory properties (especially, food palatability), volume and composition of the food (4). In addition, signals that are not related to the regulated or the controlled variables can also influence the system (5). Under certain circumstances, these latter two ...