![]()

CHAPTER 1

To the City

Under the melodramatic roar of the “El,” encircled by hash-houses and Turkish baths, are the shops of hard-boiled, stalwart men, who shyly admit that they are dottles for love, sentiment, and romance. Apprentices, dodging among the hand-carts that are forever rushing to and from the fur and garment districts, dream of the time when they will have their own commission houses. Greeks and Koreans, confessing that they have the hearts of children, build little Japanese gardens. Greenhouse owners declare that they would not sell—at any price— the flowers which grow in their own backyards. A dealer plans how to improve the business that his grandfather started. And orchids in milk-bottles nod at field-flowers in buckets.

—Jane Butzner, “Flowers Come to Town,” 1937

In 1934, at eighteen, Jane Jacobs (then Jane Butzner) left her hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, for New York City, the great metropolis a hundred miles to the southeast, to begin her career as a writer. Although she did not start writing her best-known book for another two and a half decades, moving to New York was the beginning of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which she later dedicated “TO NEW YORK CITY.” Without Jacobs’s experiences there, it is difficult to imagine her writing Death and Life and many of the books that followed.1

Cities, as Jacobs later described them in Death and Life—where she typically resisted figurative language despite her early interest in poetry— were lights in the darkness. Although mindful of the analogical fetishes frequent among theorists of architecture and cities, and believing that a city could be best understood “in its own terms, rather than in terms of some other kinds of organisms or objects,” she could not resist an analogy here. Imagine, she told her readers, a large, dark field, where “many fires are burning. They are of many sizes, some great, others small; some far apart, others dotted close together; some are brightening, some are slowly going out. Each fire, large or small, extends its radiance into the surrounding murk, and thus it carves out a space.” Cities were light and life, and New York was the great fire in the darkness. “Life attracts life,” she wrote in Death and Life. The aphorism, although she did not relate it in the book to her personal experiences, was rooted in her biography: Jacobs understood the attractive powers of great cities from an early age.2

Changing rapidly, New York was also the best of places, and the 1930s were perhaps the best of times, to observe great American city dynamics at work. On its way to becoming the greatest of American cities and one of the greatest of the world’s great cities, New York was The City for many Americans and immigrants, and Jacobs was one of them. In 1935, Berenice Abbott, who later became Jacobs’s friend, described her Changing New York photographic exhibition as witnessing “the end of something.” It was the end of premodern New York.3

Consolidated in 1898 and home to the world’s tallest building by 1913, New York City had a population that doubled from approximately three and a half to seven million people between 1900 and 1935. Housing shortages and traffic congestion were already problems; slum clearance housing projects and, by the mid-1920s, highway projects were deemed necessary. Only sixteen years after Henry Ford’s Model T automobile came to market, in the 1924 New York Times article “New York of the Future: A Titan City,” the city’s police commissioner called for the building of elevated highways: “Commissioner Enright has announced his conclusion that New York is already at the saturation point. Already the motor car, designed to accelerate movement, has by its very multiplicity defeated itself. Consequently the traffic officer has become the town planner.” The same article compared New York to Chicago, where “deep in the heart of the town, tenements are being torn down to make way for spacious new thoroughfares.” What of New York? “While Chicago talks of its conception of a ‘city beautiful’ and works prodigiously, has New York, the greater city, no far-flung plans?” Was it “timid in the face of imperial ideas, parsimonious at the thought of vast public expenditures?” The answer was no, it was not. New York would not be bested.4

FIGURE 2. Oak and New Chambers streets, Lower East Side, as captured in 1935 as part of Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York WPA photography project. The area was destroyed in 1959 for an expansion of the adjacent civic center. New York Public Library.

By 1935, when Jacobs published her first writing on the city, New York was recovering from the Great Depression and determined to shed the trappings of the nineteenth century. Historically, the city was organized in a tight pedestrian neighborhood pattern of what later became called “Jane Jacobs blocks”—where all daily needs could be satisfied by walking one or two self-sufficient blocks containing a grocery store, barbershop, newsstand, butcher, drugstore, deli, laundry, flower shop, cobbler, stationer, bar, hardware store, bakery, and so on. “So complete is each neighborhood, and so strong the sense of neighborhood, that many a New Yorker spends a lifetime within the confines of an area smaller than a country village,” wrote E. B. White in Here Is New York in 1949. “Let him walk two blocks from his corner and he is in a strange land and will feel uneasy till he gets back.”5

Yet, prompted by new building techniques and means of transportation, the time was ripe to think about the “modern” city—for new ideas about city planning and civic art, land use, building and rebuilding, rapid transit and highways, housing and new communities, parks and open space, and skyscrapers. As the authors of the Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs observed in 1929, “In spite of the great changes that have come over cities in connection with the development of vehicular transportation and steel construction, and of the imminence of new changes as a result of the development of the airplane, much of what may be called ‘medievalism’ persists in the modern city.” “Skyscrapers are as modern as the motor car. Their influence has been great but has really only begun to be felt,” they predicted. Land use needed to be reconsidered to provide skyscrapers with appropriate breathing room. “The skyscraper mountains enclose working places that are little better lighted and ventilated than mines. … Why can we not have the skyscraper and still get sufficient daylight for it and other buildings?” they asked. Modern architects like Le Corbusier certainly agreed. But Le Corbusier, who visited New York in 1935, and experienced firsthand the city so frequently referenced as an inspiration and counterexample in his City of To-Morrow and Its Planning (1929), was not alone. A city organized to provide its residents with sunlight, fresh air, green spaces, decent housing, and ease of movement seemed only natural and common sense.6

Indeed, many of the goals and ambitions of postwar urban renewal were established in the 1930s. The decade epitomized the “creative destruction” of Manhattan and anticipated the urban renewal era of the 1950s and 1960s. Apart from the construction of highways and parkways that sought to reduce congestion and traffic fatalities and make new commuter suburbs accessible, the first public housing project in the United States, First Houses, was dedicated on December 3, 1935, by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Modest but expensive, it was a housing experiment clearly inadequate as a model for growing housing needs. With New York’s population growth showing no signs of slowing, the plans on drawing boards were ever more ambitious. Thus, while visionaries and reformers like Le Corbusier and the writer Lewis Mumford imagined more humane “Radiant Cities” and “Garden Cities,” the problem of quickly supplying a huge number of dwellings, and making them affordable, resulted in designs that privileged quantity over quality. The “pathology of public housing,” which Jacobs would observe in East Harlem two decades later, had its roots during this period.7

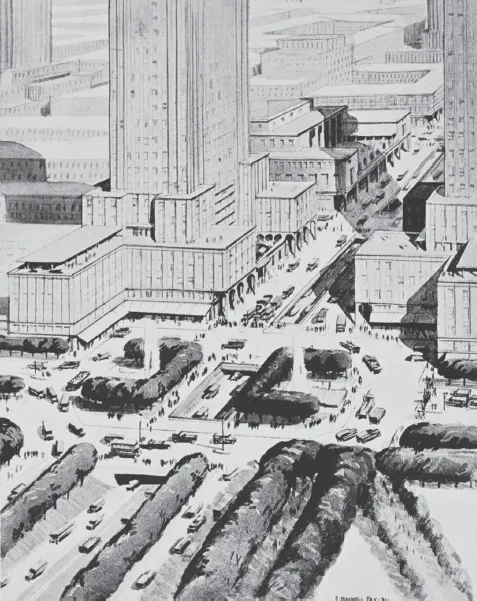

FIGURE 3. A conception of the modern city with “proper restraint of height and density of building, together with well balanced distribution of ground space, overground space above lower buildings and occasional high towers,” and a “sunken road for fast vehicular traffic.” Thomas Adams et al., The Building of the City, Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: William F. Fell, 1931). Rendering by Maxwell Fry.

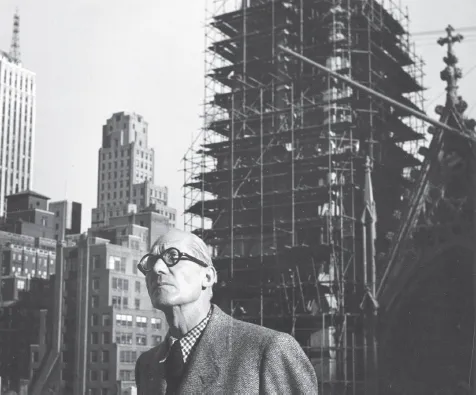

FIGURE 4. Le Corbusier in New York, 1935. Getty Images.

In the meantime, Jacobs’s thesis of city “death and life” was also evolving. From 1935, Jacobs’s earliest writing on the city reveals that she understood that cities and their neighborhoods changed over time, declining and regenerating. “Unslumming and Slumming,” the title of Death and Life’s fifteenth chapter, described this urban dynamic from the point of view of human geography and the self-regeneration of neighborhoods. It was, in part, a personal story. Describing Greenwich Village, where she made her home soon after moving to New York, as an “unslummed former slum” in Death and Life, Jacobs recognized herself as having participated in the spontaneous and historic processes of city decline and regeneration that were of central importance to the book and to her understanding of cities.8

Seeking Her Fortune

Viewed from the dark hills of northeastern Pennsylvania, New York City was a great bright light on the horizon. While Scranton’s economic lights had started flickering amid the increasing turbulence of competition in its coal and steel industries before the Great Depression, New York grew into a great city. The sparkle of New York’s ebullient Jazz Age had dimmed but was not out: The recently completed Chrysler and Empire State buildings were shiny and new, even if largely vacant, and Rockefeller Center, where Jane Jacobs would later work, was pushing rapidly skyward. With a similar resolve, Jacobs later stated, “I came to New York to seek my fortune, Depression or no.”9

By moving to a great city when she came of age, from a place with fewer opportunities to one where she could experience the richness of city life, Jacobs participated in not only a universal human tradition, but also one familiar in her family. Her mother, Bess Robinson, a nurse who grew up in a small Pennsylvania town, and her father, John Butzner, a doctor who grew up on a Virginia farm, had met in Philadelphia, where they studied and worked before moving to Scranton. Both found city life superior to rural life, and they shared their experiences with Jane and her three siblings (Elizabeth, James, and John), understanding their children’s desires and perhaps need to move from Scranton to pursue their livelihoods. Jane’s older sister, Betty, who had studied interior design in Philadelphia, had already settled in New York.10

In her youth, Jane had decided to pursue a career as a writer. Around the age of eleven, she became serious about poetry and quickly discovered the satisfaction and praise of publication for pieces first published in a local newspaper and in the Girl Scouts’ widely circulated American Girl magazine in 1927. Although her interest in creative writing continued into adulthood (she continued to write poetry and tried fiction in the mid-1950s, just before becoming significantly involved in urban renewal controversies), her focus turned to nonfiction in high school.

Following graduation from Scranton’s Central High School in early 1933 and a subsequent training course in stenography at Powell Business School, she was “thoroughly sick of attending school and eager to get a job, writing or reporting,” as she described that time in her life in a rare autobiography. In August 1933, she found a job with the Scranton Republican, and, until the newspaper was sold to the Scranton Tribune in June 1934, Jacobs worked as an assistant to the society editor but soon took on the responsibilities of assistant editor, covering events like civic meetings and arts reviews, and laying out the Society page, a task previously left to the composing room foreman but later adopted by other departments of the paper. On her own initiative, she assumed the role of cub reporter, seeking out and developing her own feature stories for the city desk.11

Laid off from the newspaper and still too young to move away from home, Jacobs spent six months, between May and November 1934, with an aunt who directed a Presbyterian mission in Higgins, North Carolina, a hamlet that was a pinprick of light barely illuminating the darkness of the Appalachian Mountains. Her experience there, referenced directly and indirectly in her books decades later, made a deep impression. As she later explained in Cities and the Wealth of Nations, Higgins (which she called Henry in the book) had been dying for over a century, all but cut off from the economies of cities for about a century and a half. Becoming increasingly isolated, the settlement, she wrote, “proceeded to shed and lose traditional practices and skills after it had lost almost all contact and interchange with the economies of cities,” eventually reverting to a subsistence economy. In a notable anecdote, Jacobs recounted how her aunt’s parishioners had argued against building a church made of stone, despite being surrounded by Blue Ridge Mountain granite. According to Jacobs, the townspeople had lost both the masonry skills and ambitions of their forbears, who had built stone parish churches, even great cathedrals, from time immemorial. “Having lost the practice of construction with stone, people had lost the memory of it, too, over the generations,” she wrote, “and having lost the memory, lost the belief in the possibility—until a mason arrived from the nearest city, Asheville, and got them started on a church of small stones.” The anecdote was meant to exemplify how cities, as dense repositories of culture, perpetuated even those practices typically considered innately rural.12

Regardless of why Higgins’s townfolk may have opposed building a stone church, Jacobs’s experiences there were fresh in her mind weeks later, when she arrived at her sister’s apartment in Brooklyn in November 1934. The contrast, of course, could not have been greater. While the people of Higgins, surrounded by stone, apparently found the prospect of building a small stone church daunting, in New York one of the largest private building projects in modern times, Rockefeller Center, clearly showed that a great city could withstand even a great economic depression. Although Jane would struggle to find any work, and she and Betty would be reduced to eating baby cereal, the cheapest food they could find, by the end of 1934, New York had seen the worst of the Depression and there was a sense of cautious optimism in the air. The Central Park “Hooverville” was gone, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt was promising the American people a “New Deal.” New York, offering promise for the nation at large, suggested that robust cities would not succumb to Higgins’s fate.

FIGURE 5. Jane Jacobs’s high school graduation photo, January 1933. Jacobs Papers.

Unable to find a position with a magazine or newspaper, Jacobs looked for part-time work and freelance writing opportunities. She made the most of job hunting, which turned out to be a good way to get to know the city’s neighborhoods and business districts. From her first New York home, a six-story walkup on Brooklyn’s Orange Street (later destroyed by the Cadman Plaza renewal project), and later from Greenwich Village, where she and Betty moved in October 1935, Jacobs explored Manhattan as she answered want ads, sometimes getting off the subway at random stops for the surprise of discovering the marvels of the city, which inspired her to continue her poetry writing. In this way she discovered the working districts of the city, whose vitality, largely undiminished by the economic situation, afforded her some employment and whose energy and complexity captured her imagination after her time in Appalachia.13

Jacobs would spend most of the years from 1935 to 1938, when she started college at Columbia University, in Manhattan’s working districts, employed as a secretary at various New York manufacturing businesses. Her writing career would not be...