![]()

I

TOURISM AND LEISURE:

A THEORETICAL OVERVIEW

Tourism as a manifestation of leisure presupposes a socioeconomic milieu in which money and time-away-from-work can be accumulated to be spent at will. Tourism as a form of mobility suggests that culturally sanctioned reasons exist for leaving home to travel. In this theoretical introduction to the nature of tourism, Nelson Graburn in chapter 1 traces the history of tourism and discusses why tourism arose in the forms in which it exists today. In chapter 2, Dennison Nash considers the economic bases for tourism, and why tourism arose in the places where it is found today. Both authors treat tourism as an organized industry, catering to a clientele who have time and money and want to spend them, pleasurably, in leisured mobility or migration.

![]()

1

Tourism: The Sacred Journey

NELSON H. H. GRABURN

The human organism . . . is . . . motivated to keep the influx of novelty, complexity, and information within an optimal range and thus escape the extremes of confusion [This is Tuesday, so it must be Belgium] and boredom [We never go anywhere!].

D. Berlyne (1962, p. 166)

The anthropology of tourism, though novel in itself, rests upon sound anthropological foundations and has predecessors in previous research on rituals and ceremonials, human play, and cross-cultural aesthetics. Modern tourism exemplifies that part of the range of human behavior Berlyne calls “human exploratory behavior,” which includes much expressive culture such as ceremonials, the arts, sports, and folklore; as diversions from the ordinary, they make life worth living. Tourism as defined in the introduction does not universally exist but is functionally and symbolically equivalent to other institutions that humans use to embellish and add meaning to their lives. In its special aspect—travel—it has antecedents and equivalents in other seemingly more purposeful institutions such as medieval student travel, the Crusades, and European and Asian pilgrimage circuits.

All Work and No Play Makes Jack a Dull Boy

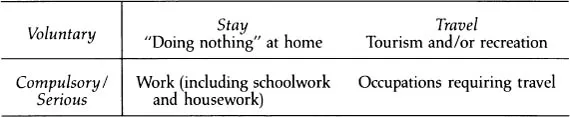

A major characteristic of our conception of tourism is that it is not work, but is part of the recent invention, re-creation, which is supposed to renew us for the workaday world, a point emphasized by Nash (chapter 2). Tourism is a special form of play involving travel, or getting away from “it all” (work and home), affording relaxation from tensions, and for some, the opportunity to temporarily become a nonentity, removed from a ringing telephone. Stemming from our peasant European (or East Asian) traditions, there is a symbolic link between staying: working and traveling: playing, which may be expressed as a model (Figure 1).

Norbeck (1971) points out that in Western society and Japan, and particularly in Northern European-derived cultures, the work ethic is so important that very strong moral feelings are attached to the concepts of work and play, including an association of what is “proper” in time and place. From the model, compulsory or serious activities such as making a living properly take place in the workaday world and preferably “at home.” Conversely, “proper” travel is voluntary, does not involve routine work, and therefore is “good for you.” A majority of Americans and Europeans see life as properly consisting of alternations of these two modes of existence: living at home and working for longish periods followed by taking vacations away from home for shorter periods. However, some sanctioned recreation is often an other kind of “hard work,” especially in the rites-of-passage or self-testing types of tourism such as those of youthful travelers (Teas 1976; Vogt 1978). Many tourists admittedly return home to “rest up” from their vacations.

Figure 1. Working/traveling matrix.

The model also indicates that staying at home and not working is considered improper for normal people. Many would complain that to not go away during vacations is “doing nothing” as if the contrasting “something” must take place away from home or it is “no vacation at all.” The very word vacation comes from the Latin vacare, “to leave (one’s house) empty,” and emphasizes the fact that we cannot properly vacation at home.1 People who stay home for vacation are often looked down upon or pitied, or made to feel left behind and possibly provincial, except for the aged and infirm, small children, and the poor. Within the framework of tourism, normal adults travel and those who do not are disadvantaged.

By contrast, able-bodied adults who do not work when living at home are also in a taboo category among contemporary Western peoples. If they are younger or poorer they are labelled “hippies,” “bums,” or even “welfare chiselers”; otherwise they may be labeled the “idle rich.” In both cases, most people consider them some kind of immoral parasites.

The other combination—work that involves compulsory travel—is equally problematic. Somehow, it is improper to travel when we work, as it is improper to work when we travel. The first category includes traveling salesmen, gypsies, anthropologists, convention goers, stewards, and sailors, and our folklore is full of obscene jokes about such people—for their very occupations are questionable, whatever their behavior! Alternately, people on vacation don’t want to work, and justifiably complain about their “busman’s holiday.” Among them are housewives whose families, to save money, rent a villa rather than stay in a hotel; doctors who are constantly consulted by their co-travelers; and even anthropologists who are just trying to vacation in a foreign country.

To Tour or Not to Tour: That Is the Problem

Tourism in the modal sense emphasized here is but one of a range of choices, or styles, of vacation or recreation—those structurally-necessary, ritualized breaks in routine that define and relieve the ordinary. For the present discussion our focus is consciously on the more extreme examples of tourism such as long distance tours to well-known places or visiting exotic peoples, in the most enchanting environments. However, the most minimal kinds of tourism, such as a picnic in the garden, contain elements of the magic of tourism. The food and drink might be identical to that normally eaten indoors, but the magic comes from the movement and the nonordinary setting. Furthermore, it is not merely a matter of money that separates the stay-at-homes from the extensive travelers. Many very wealthy people never become tourists, and most “youthful” travelers are, by Western standards, quite poor.

The stay-at-home who participates in some creative activity such as remodeling the house, redoing the garden, or seriously undertaking painting, writing, or sports activities, shares some of the values of tourism in that recreation is involved that is nonordinary and represents a voluntary self-indulgent choice on the part of the practitioner. Still others who, through financial stringency or choice, do not go away during vacations but celebrate the released time period by making many short trips, take the nonworkaday aspects of the vacation and construct events for the satisfaction of their personal recreational urges. Even sending the children away to camp may count as a vacation for some parents. Though not tourism in the modal sense, camping, backpacking, renting a lake cottage, or visiting relatives who live far away function as kinds of tourism, although their level of complexity and novelty may not be as high.

The Sacred and the Profane, or, A Change is as Good as a Rest

Taking our cue from Berlyne, who suggests that all human life tries to maintain a preferred level of arousal and seeks “artificial sources of stimulation . . . to make up for shortcomings of their environment” (Berlyne 1968, p. 170), tourism can be examined against its complement: ordinary, workaday life. There is a long tradition in anthropology of the structural examination of events and institutions as markers of the passage of natural and social time and as definers of the nature of life itself. This stems partly from Durkheim’s (1912) notions of the sacred—the nonordinary experience—and the profane. The alternation of these states and the importance of the transition between them was first used to advantage by Mauss (1898) in his analysis of the almost universal rituals of sacrifice, which emphasized the process of leaving the ordinary, i.e., sacralization that elevates participants to the nonordinary state wherein marvellous things happen, and the converse process of desacralization or return to ordinary life.

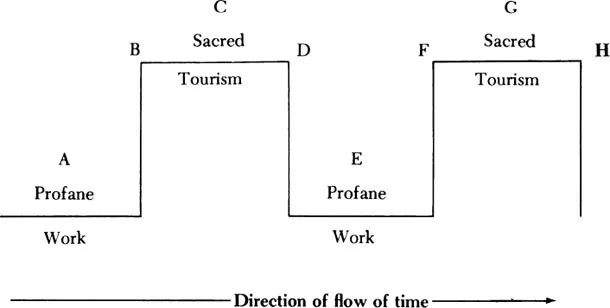

Leach (1961, pp. 132–36), in his essay on “Time and False Noses,” suggests that the regular occurrence of sacred-profane alternations marks important periods of social life or even provides the measure of the passage of time itself. The passing of each year is usually marked by the annual vacation (or Christmas), and something would be wrong with a year if it didn’t occur, as if one had been cheated of time. “The notion that time is a ‘discontinuity of repeated contrasts’ is probably the most elementary and primitive of all ways of regarding time. . . . The year’s progress is marked by a succession of festivals. Each festival represents a temporary shift from the Normal-Profane order of existence into the Abnormal-Sacred order and back again.” The total flow of time has a pattern, which may be represented as in Figure 2.

Vacations involving travel, i.e., tourism, since all “proper” vacations involve travel, are the modern equivalent for secular societies to the annual and lifelong sequences of festivals for more traditional God-fearing societies. Fundamental is the contrast between the ordinary/ compulsory work state spent “at home” and the nonordinary/ voluntary “away from home” sacred state. The stream of alternating contrasts provides the meaningful events that measure the passage of time. Leach applies the diagram to “people who do not possess calendars of the Nautical Almanac type,” implying that those who have “scientific” calendars and other tacit reminders such as newspapers, radio, and TV rely on the numerical calendar. I believe the “scientific, secular” Westerner gains greater meaning from the personal rather than the numerical in life. We are happier and better recall the loaded symbolic time markers: “That was the year we went to Rome!” rather than “that was 1957,” for the former identifies the nonordinary, the festive, or ritual.

Figure 2. Flow of time pattern (after Leach 1961: 134).

Each meaningful event marks the passage of time and thus life itself. Each secular or sacred period is a micro-life, with a bright beginning, a middle, and an end, and the beginnings and endings of these little “lives” are marked by rituals that thrust us irreversibly down life’s path. Periods A and C in Figure 2 are both segments of our lives but of a different moral quality. The profane period, A, is the everyday life of the “That’s life!” descriptive of the ordinary and inevitable. The period of marginality, C, is another life, which, though extraordinary, is perhaps more “real” than “real life.” Vacation times and tourism are described as “I was really living, living it up . . . I’ve never felt so alive,” in contrast to the daily humdrum often termed a “dog’s life,” since dogs are not thought to “vacation.” Thus, holidays (holy, sacred days now celebrated by traveling away from home) are what makes “life worth living” as though ordinary life is not life or at least not the kind of life worth living.

Our two lives, the sacred/nonordinary/touristic and the profane/ workaday/stay-at-home, customarily alternate for ordinary people and are marked by rituals or ceremonies, as should the beginning and end of lives. By definition, the beginning of one life marks the end of the other. Thus, at time B, we celebrate with TGIF (Thank God It’s Friday) and going-away parties, to anticipate the future state and to give thanks for the end of the ordinary. Why else would people remain awake and drink all night on an outbound plane en route to Europe when they are going to arrive at 6:40 A.M. with a long day ahead of them? The re-entry ritual, time D, is often split between the ending-party—the last night in Europe or the last night at sea—and the welcome home or welcome back to work greetings and formalities, both of which are usually sadder than the going away.

In both cases the transition formalities are ambivalent and fraught with danger or at least tension. In spite of the supposedly happy nature of the occasion, personal observation and medical reports show that people are more accident prone when going away; are excited and nervous, even to the point of feeling sick; and Van Gennep (1914) suggests that the sacralization phase of symbolic death lies within our consciousness. It is implied in phrases such as “parting is such sweet sorrow” or even “to part is to die a little.” Given media accounts of plane, train, and automobile accidents, literally as tourists we are not sure that we will return. Few have failed to think at least momentarily of plane crashes and car accidents or, for older people, dying while on vacation. Because we are departing ordinary life and may never return, we take out additional insurance, put our affairs in order, often make a new will, and leave “final” instructions concerning the watering, the pets, and the finances. We say goodbye as we depart and some even cry a little, as at a funeral, for we are dying symbolically. The most difficult role of a travel agent is to hand someone their tickets to travel to a funeral, for the happy aspect of the journey is entirely absent, leaving only a double sorrow.

The re-entry is also ambivalent. We hate to end vacation, and to leave new-found if temporary excitement; on the other hand, many are relieved to return home safely and even anticipate the end of the tense, emotion- charged period of being away. We step back into our former roles (time E), often with a sense of culture shock. We inherit our past selves like an heir to the estate of a deceased person who has to pick up the threads, for we are not ourselves. We are a new person who has gone through re-creation and, if we do not feel renewed, the whole point of tourism has been missed.

For most people the financial aspects of tourism parallel the symbolic. One accumulates enough money with which to vacation, much as one progressively acquires the worries and tedium of the workaday world. Going away lightens this mental load and also one’s money. Running out of money at the end of the holiday is hopefully accompanied by running out of cares and worries—with the converse accumulation of new perspectives and general well-being. The latter counteracts the workaday worries with memories of the more carefree times. In turn, they stimulate the anticipation and planning for the next vacation, and F and G will be different from B and C because we have experienced times A through E.

While traveling, each day is a micro-model of the same motif. After the stable state of sleep, the tourist ventures forth to the heightened excitement of each new day. Nightfall is often a little sad for the weary tourist; the precious vacation day is spent. Perhaps the often frantic efforts at nightlife on the part of tourists who may never indulge at home are attempts to prolong the “high”—to remain in the sacred, altered state—and delay the “come down” as long as possible.

The Profane Spirit Quest: The Journey Motif in Tourism

Life is a succession of events marked by changes in state. It is both cyclical, in that the same time-marking events occur day after day, year after year, and it is progressive or linear in that we pass through life by a series of changes in status, each of which is marked by a different (though similarly structured) rite of passage. An almost universal motif for the explanation and description of life is the journey, for journeys are marked by beginnings and ends, and by a succession of events along the way.

The travel involved in tourism is more than geographical motion or a symbolically-altered state. For Westerners who value individualism, self- reliance, and the work ethic, tourism is the best kind of life for it is sacred in the sense of being exciting, renewing, and inherently self-fulfilling. The tourist journey is a segment of our lives over which we have maximum control, and it is no wonder that tourists are disappointed when their chosen, self-indulgent fantasies don’t turn out as planned.

A journey is seldom without purpose, but culturally-specific values determine the goals of travel. In many American Indian societies, a young man left the camp alone to travel and suffer, and to meet the right spirit in order to advance to the next higher status on the journey through life. In India, in medieval Europe, and in the Islamic world, people made difficult pilgrimages to find spiritual enlightenment. Visitors to Las Vegas are also enlightened and often return home with a flat wallet, having sacrificed dearly for their pleasures.

Even if one regards tourism as voluntary, self-interested travel, the tourist journey must be morally justified by the home community. Because the touristic journey lies in the nonordinary sphere of existence, the goal is symbolically sacred and morally on a higher plane than the regards of the ordinary workaday world. Tourists spend substantial sums to achieve the altered state—money that could be invested for material gain or alternately used to buy a new car or redecorate their homes.

“Human exploratory behavior,” says Berlyne (1968, p. 152), “is behavior whose principle function is to change the stimulus field and introduce stimulus elements that were not previously accessible.” Thus, as art uplifts and makes meaningful the visual environment, so tourism provides an aesthetically appropriate counterpoint to ordinary life. Tourism has a stated, or unstated but culturally determined, goal that has changed through the ages. For traditional societies the rewards of pilgrimages were accumulated grace and moral leadership in the home community. The rewards of modern tourism are phrased in terms of values we now hold up for worship: mental and physical health, social status, and diverse, exotic experiences.

In medieval Europe, travel was usually for avowedly religious purposes, as were pilgrimages and crusades; for ordinary people travel was difficult and dangerous, and even for the ruling classes, who also traveled for reasons of state, travel required large protective entourages. Those who could afford it often retired to retreats or endowed religious institutions in their spiritual quest for the ultimate “truth.” It was the Renaissance that cha...