![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

For the past sixteen years I have been walking the streets and public spaces of the city and watching how people use them. Some of what I found out may be of practical application. The city is full of vexations: steps too steep; doors too tough to open; ledges you cannot sit on because they are too high or too low, or have spikes on them so that undesirables will not sit on them. It is difficult to design an urban space so maladroitly that people will not use it, but there are many such spaces. On a larger scale, there are big blank walls, whole block-fronts of them, fortresslike megastructures; atriums; and enclosed malls. There are concourses underground and skyways overhead, made the more disorienting with illuminated maps that you cannot decipher. Small problems or large, there are practical ways to deal with them and I shall be suggesting some—including a definitive solution to the blank wall.

But there is much to be encouraged about too. The rediscovery of the pleasures of downtown has been made in city after city. To take just one index, there has been a marked increase in the number of people using center city spaces. This is in good part because there has been a marked increase in the number of spaces created. Some of them have indeed been maladroitly designed; but many are not, and a few are superb. My research group kept fairly precise count of key spaces and found that beginning in the early seventies the year-to-year increase in daily use of key spaces averaged about 10 percent. Supply was creating demand; not only were there more spaces each year, but more people were getting in the habit of using them. In time, spaces reach an effective capacity, one that is surprisingly large and is nicely determined by people themselves. Much has been learned about the factors that make a place work, and they have been applied to good effect in some stunning locations. (One of our principal findings: people tend to sit most where there are places to sit.)

There has been a proliferation of outdoor cafés. Not so long ago, the conventional wisdom was that Americans would enjoy alfresco dining on trips to Europe but were too Calvinistic to do so at home. Today a number of once-staid cities have an outdoor ambiance in spring and summer that is almost Mediterranean. Washington is an excellent example.

The rediscovery of the center seems to be a fairly universal phenomenon. In European cities, which have had a head start on ours in the provision of congenial spaces, there has been a widespread increase in the peopling of downtown. The outstanding example is Copenhagen. Thanks in good part to proselytizing by architect Jan Gehl, the center has been pedestrianized to dramatic effect. Gehl has kept detailed records, and they show a dramatic increase in the simple pleasures of downtown—strolling, sitting, window shopping. They also show great increases in planned and unplanned activities, even in winter. A new “tradition,” started in 1982, is the Copenhagen Carnival, a three-day affair that has people samba dancing their way to the center.

A good part of this book is concerned with the practical, and in particular, the design and management of urban spaces. But my main interest has been in matters much less practical—or, as I would prefer to term it, fundamental research. Whatever may be the significance, what is most fascinating about the life of the street is the interchanges between people that take place in it. They take many forms. I will take them up in detail in the next chapter, but let me here note a few.

The most basic is what we term the 100 percent conversation—that is, the way people who stop to talk gravitate to the center of the pedestrian traffic stream. A variant is the prolonged, or three-phase goodbye. Sometimes these go on interminably, with several failed goodbyes as preface to the final, climactic one.

Schmoozers are instructive to watch. When they line up on the sidewalk, along the curb most often, they may engage in an intricate foot ballet. One man may rock up and down on his feet. No one else will. He stops. In a few seconds another man will start rocking up and down on his feet. A third man may turn in a half circle to his right and then to his left. There seems to be some process of communication going on. But what does it mean? I have not broken the code.

Another source of wonder is the skilled pedestrian. He is really extraordinary in the subtleties of his movements, signals, and feints. I will analyze some instant replays of crossing patterns and averted collisions as testimony.

Let me tell briefly how all this got started. In 1969, Donald Elliott, then the chairman of the New York City Planning Commission, asked me to help its members draft a comprehensive plan. It was an enjoyable task, for Elliott had gathered together a very able group of young architects, planners, and lawyers. Moreover, the thrust of the plan was unusually challenging: it was concerned with the major issues of the growth and workability of the city and its government rather than with specific land-use projections and the kind of futuristic projects typical of such plans. There was also a strong emphasis on urban design and the use of incentive zoning to provide parks and plazas. New York was doing the pioneering in this area, and the text was properly self-congratulatory on the matter.

One thing I did wonder is how the new spaces were working out. There was no research on this. There was no budget line for it, no person on the staff whose job it was to go out and check whether the place was being well used or not, and if not, why. It occurred to me that it would be a good idea to set up an evaluative unit to fill the vacuum.

I got a break. Under another innovative New York program, I was invited to Hunter College as a Distinguished Professor. (What a splendid title! Translation: no doctorate; here only one year.) Through Hunter’s estimable sociology department, I was able to put the arm on some students to do studies of particular places. Some of the studies were excellent. They were also a demonstration of how the times can color perceptions. This was during the period of campus unrest—the president of the college was regularly hung in effigy—and the students’ studies of spaces in and around the college tended to indicate that the whole place was a lousy plot. Nearby Madison Avenue was viewed as a hostile place, and with some justification. Whatever the subjective factors, however, some of the students proved very good at observation, and this fortified my belief in the viability of a small evaluative group.

I applied for grants to set up a unit. One of the first applications was to the trustees of the Research Division of the National Geographic Society. The gist of my application was that they had supported observational studies of far-off peoples and far-off places, so why not the natives of a city? They thought it a bit cheeky, but they did like the argument. They gave me a grant—an “expedition grant” actually—the first domestic one they had made. (I had to submit an expedition-leader form as to whether the members had been inoculated against likely tropical diseases.)

A word about methodology. Direct observation was the core of our work. We did do interviewing, and occasionally we did experiments. But mostly we watched people. We tried to do it unobtrusively and only rarely did we affect what we were studying. We were strongly motivated not to. Certain kinds of street people get violent if they think they are being spied upon.

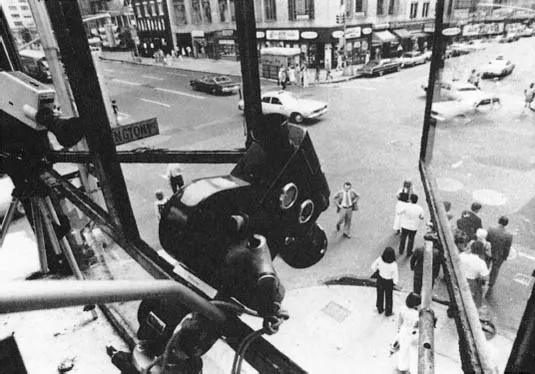

We used photography a lot: 35mm for stills, Super 8 for time-lapse, and 16mm for documentary work. With the use of a telephoto lens, one can easily remain unnoticed, but we found that the perspective was unsatisfactory for most street interchanges. We moved in progressively closer until we finally were five to eight feet from our subjects. With a spirit level atop the camera and a wide-angle lens, we could film away with our backs half turned and thus remain unnoticed—most of the time.

The image of the city of the documentaries: Fifth Avenue through a telephoto lens; eight blocks of people squeezed into one, tense, unsmiling; on the sound track, jackhammers and sirens, a snatch of discordant Gershwin.

Our first studies were concerned with density. They had to be. In the late sixties and early seventies the spectre of overcrowding was a popular worry. High density was under attack as a major social ill and so was the city itself. “Behavioral sink” was the new pejorative. The city was being censured not only for its obvious ills but for the compression that is a condition of it. Fifth Avenue through a telephoto lens: eight blocks of people, tense and unsmiling, squeezed into one; on the soundtrack, jackhammers, sirens, and a snatch of discordant Gershwin. This was the image of the city of the documentaries. Was there hope? Yes, a bright hope, says the narrator. A little child is shown running up a grassy hill in a new town. Back in the city, crews with hard hats and wrecking balls are shown demolishing old buildings. They are the good guys. As children look on, up go high, white towers, like Le Corbusier’s radiant city. And they came to pass, these utopias, and with the best of intentions.

There were many studies on density. Notable was the work of Dr. John Calhoun of the National Institutes of Health. In experiments with rats and mice, he found that varying degrees of crowding correlated with neurotic and sometimes suicidal behavior. There were university studies on the effects on people of different space configurations, such as how twenty people in a circle in room A performed a task as compared with the same number performing the same task in a square in room B. Another approach was to monitor people’s physiological responses as they were shown pictures of different spaces, ranging from a crowded street to a wilderness glade.

Perch at Lexington and Fifty-seventh Street. We used a battery of cameras to track pedestrian flows, street corner encounters, and the daily life of the newsstand at right.

Some of the studies were illuminating. Taken together, however, they suffered one deficiency: the research was vicarious; it was once or twice removed from the ultimate reality being studied. That reality was people in everyday situations. That is what we studied.

The concern over high density was peaking just about the time it was becoming obvious that cities were not gaining people but losing them. Harlem, exhibit number 1 in the documentaries, experienced a severe decline, losing some 25 percent of its population between 1950 and 1970. It was not the better for it. There were so many burnt-out buildings and empty lots as to provide the worst of two worlds: not enough people in many areas to sustain the stores and activities that make a block work, but severe overcrowding in the buildings that remained. A block that did work was one we studied on East 101st Street, in Spanish Harlem. It had its troubles, but it functioned well as a small, cohesive neighborhood. Among the reasons was that there was only one vacant lot, and that was made into the block’s play area.

The momentum of Title I redevelopment programs was still in force. The idea had been to empty out the blighted areas of the inner city and replace them with lower-density high-rise projects. Many of the areas were not truly blighted, but the expectation was self-fulfilling. Once an area was declared blighted, maintenance ceased, and long before yuppies came along, the displacement of people was under way. Sometimes the redevelopment phase never did come about. To this day, there are cities with swaths of cleared space in limbo: Boise, Idaho, which came near destroying itself, still has many blocks awaiting redevelopment.

Too much empty space and too few people—this finally emerged as the problem of the center in more cities than not. It had been the problem for a long time, but the lag in recognizing it as such was lamentably long. This was particularly the case with smaller cities; for many of them it still is.

It is a well-known fact that small cities are friendlier than big ones. Our research indicates that the reverse is more likely to be the case.

It is a well-known fact that small cities are friendlier than big ones. But are they? Our research on street life indicates that, if anything, the reverse is more likely to be the case. As far as interaction between people is concerned, there is markedly more of it in big cities—not just in absolute numbers but as a proportion of the total. In small cities, by contrast, you see fewer interchanges, fewer prolonged good-byes, fewer street conferences, fewer 100 percent conversations, and fewer 100 percent locations, for that matter. Individually, the friendliness quotient of the smaller might be much higher. As a former resident of a small town, I would think this to be true. It could also be argued that friendships run deeper in a smaller city than in a larger one. As far as frequency of interchange is concerned, however, the streets of the big city are notably more sociable than those of a smaller one.

It is not a question of the overall population, but of its distribution. A small city with a tight core can concentrate more people in its center than a larger one that sprawls all over the place. But most small cities do not concentrate; indeed, few have the concentration that they once had. Blockfront after blockfront has been broken up, the continuity destroyed by a miscellany of parking lots. Some cities have gone over the 50 percent level in this respect, with more area in parking than city.

When I visit a city, I like to take some quick counts in the center of town at midday. If the pedestrian flows on the sidewalks are at a rate less than a thousand people an hour, the city could pave the streets with gold for all the difference it would make. The city is one that is losing its center or has already done so. There are simply not enough people to make it work—not enough to keep the last department store going, not enough to sustain some good restaurants, not enough to make lively life on its streets.

It is sad to see how many cities have this emptiness at their core. It is sadder still to see how many are adopting exactly the approaches that will make matters worse. Most of their programs have in common as a stated purpose “relief from pedestrian congestion.” There is no pedestrian congestion. What they need is pedestrian congestion. But what they are doing is taking what people are on the streets and putting them somewhere else. In a kind of holy war against the street, they are putting them up in overhead skyways, down in underground concourses, and into sealed atriums and galleries. They are putting them everywhere except at street level.

In a kind of holy war against the street, cities are putting people up in overhead skyways, down in underground concourses—everywhere except street level.

One result is an effect akin to Gresham’s law: to make their substitute streets more competitive, cities have been making what is left of their real streets duller yet. One instrument is the blank wall. According to my rough computations, the proportion of downtown block-fronts that are blank at street level has been growing rapidly—most of all, in small cities, which are the ones most immediately hurt by suburban shopping malls and most tempted to fight their tormentors by copying them.

They do copy them, and it is self-defeating of them to do so. Cities for people who do not like cities are the worst of two worlds. As the National Trust’s Main Street program has been demonstrating, the approaches that work best are those which meet the city on its own gritty terms; which raise the density, rather than lower it; which concentrate, tightening up the fabric, and get the pedestrian back on the street.

But it is the big cities that face the toughest challenge. Will their centers hold? Or will they splatter into a host of semicities? At the moment, the decentralization trend seems dominant. The demographics indicate that this is the case. So do the colonies of towers going up between the cloverleafs. Even within the city, suburbia is winning. Now coming of age is a whole new generation of planners and architects for whom the formative experience of a center was the atrium of a suburban shopping mall. Some cities have already been recast in this image, and more are following suit.

I am eschewing prophecy in this book. It is hard enough to figure out what is happening now, let alone what might or might not twenty years hence. But one can hope. I think the center is going to hold. I think it is going to hold because of the way people demonstrate by their actions how vital is centrality. The street rituals and encounters that seem so casual, the prolonged goodbyes, the 100 percent conversations—these are not at all trivial. They are manifestations of one of the most powerful of impulses: the impulse to the center.

And of the primacy of the street. It is the river of life of the city, the place where we come together, the pathway to the center. It is th...