![]()

PART I

Truth, Power, and Legitimation in Truth Commission Processes

PART I explores the place of truth commissions in today’s struggles for memory, justice, and reconciliation during political transitions. It addresses the following questions: What are truth commissions? What explains their global popularity? Are they different from other fact-finding projects? What is their relationship to the state? In what ways do civil society groups mobilize for or against a truth commission’s work? Who are the members of a truth commission and what role do they play during political transitions? To what extent do truth commissions mediate or transform the struggles over the meaning of the past? What are the narrative strategies they employ while rewriting the nation’s history?

Part I sets a theoretical framework by engaging academic and policy debates in three interrelated areas: conceptual issues surrounding truth commissions and other fact-finding initiatives (Chapter 1), the politics of establishing, operating, and endorsing a truth commission (Chapter 2), and commissions’ role in the struggles for social memory (Chapter 3). While differences between commissions are highlighted, these chapters focus more on what is common across the multitude of experiences. State-society relations, political legitimation, civil society participation, commission autonomy, divisions over social memory, and the tension between forensic investigation and historiography are common themes that all truth commissions find themselves grappling with. Part I explores these themes and thus sets the stage for the empirical analyses of truth commission impact in Part II, where variation across truth commissions is analyzed in further detail.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Definition and Conceptual History

of Truth Commissions: What Are They?

What Have They Become?

Few ideas have gained as much international attention in such a short time span as the concept of the truth commission. Successful and failed initiatives to set up ad hoc panels called “truth commissions” to investigate patterns of human rights violations abound. In addition, in some countries single incidents of violence have led to calls for a commission when the facts about the event remained in the dark for decades. Two examples that come to mind are the 1985 siege and fire in Colombia’s Palace of Justice1 and the 1994 bombing of the Israeli-Argentine Mutual Association in Buenos Aires.2 Perhaps more surprisingly, so-called truth commissions or truth and reconciliation commissions were proposed to tackle issues that had little or nothing to do with massive political violence, such as banking practices in England,3 sexual abuse by a television presenter,4 educational achievement in New York City,5 and doping scandals in international cycling.6 The fashion of naming all sorts of investigatory panels “truth commissions” poses two challenges: (1) setting conceptual boundaries to enable research and discussion on postconflict truth initiatives and to avoid “concept misformation,”7 and (2) explaining how the idea of the truth commission has evolved over time to encompass such a wide variety of topics, procedures, and expectations.

In the following section, I offer a definition to set truth commissions apart from similar institutions and practices, such as governmental commissions of inquiry, civil society truth projects, courts, and human rights monitoring organizations. Next, I will introduce the notions of “incomplete truth commissions” and “frustrated truth commission attempts” to distinguish failed truth commission efforts from successfully completed ones and then employ Louis Bickford’s notion of “unofficial truth projects” to refer to nongovernmental truth-finding initiatives. Once the definitional characteristics are clarified, I will outline the ways in which the idea of the truth commission has evolved. The procedures, methodologies, timing, and political functions of truth commissions have undergone profound changes over time. Initially, governments established them with limited mandates during political transitions. The increasing role of international organizations in later transitions, along with domestic and international NGOs, brought the idea and practice of truth commissions into worldwide significance. Some of the newer commissions became increasingly more ambitious with respect to their goals and better funded compared to earlier commissions. Recently, truth commissions have been created by consolidated democracies (or authoritarian regimes not undergoing transition), rather than transitional regimes, to investigate violations that had taken place decades ago, rather than in the recent past.

Truth Commission: Definition

A truth commission is a temporary body established with an official mandate to investigate past human rights violations, identify the patterns and causes of violence, and publish a final report through a politically autonomous procedure.8

The definition above specifies five fundamental characteristics that distinguish a truth commission from other investigatory bodies. First, it operates for a limited amount of time. Permanent organizations like human rights NGOs or parliamentary human rights commissions are therefore not truth commissions.

Second, a truth commission publishes a final report summarizing the main findings and making recommendations. Usually, the report is submitted first to the political institution that had issued the commission mandate, such as the office of the president, but it is common practice to make the final report available to the general public, as well.9 Some scholars include those truth commissions that were disbanded before publishing a final report (e.g., Bolivia’s 1982 National Commission of Inquiry into Disappearances and Ecuador’s 1996 Truth and Justice Commission) in their truth commission lists. It is problematic to include these commissions without qualification because the failure to publish a final report simply violates the essential task of a truth commission, namely, to disclose information on human rights violations. In addition, a final report does not only offer publicity; its existence also affirms the autonomy of a truth commission from direct political intervention. A political authority that disbands a commission or conceals its final report interferes with the publication and dissemination of facts about human rights violations and eliminates a commission’s chances of influencing policy or social norms through its findings and recommendations. Those commissions that fail to publish a public report should be named “incomplete truth commissions.” Recognizing these commissions as a separate category corrects for biases arising from conceptual stretching and enables a deeper understanding of the conditions under which truth commission projects fail to publicize their findings and recommendations. Thus, studies of truth commission impact should either not include incomplete truth commissions in their accounts or be specific about how they are expected to generate impact on human rights policy, attitudes, and norms.

Third, a truth commission examines a limited number of past events and violations that occurred over a period of time, investigating not only incidents of violence and violations but patterns, causes, and consequences, as well.10 In other words, it establishes a circumscribed historical record. The remit may be extended to the study of a vast array of human rights violations and structural inequalities (e.g., Peru) or restricted to events and violations that affected the lives of a few hundred individuals (e.g., Paraguay). Likewise, the time period under scrutiny may be as long as forty-five years (e.g., Kenya) or as short as three years (e.g., Haiti).11 What matters for definitional purposes is that the remit and periodization are stated in the mandate establishing the commission. The bounded character of the investigation separates truth commissions from official and nongovernmental monitoring institutions that investigate ongoing violations.

Fourth, a truth commission enjoys autonomy from direct intervention by political actors. It is possible to confuse presidential or parliamentary investigatory commissions with truth commissions, as truth commissions are also established by presidential (e.g., Argentina and Chile), parliamentary (e.g., Ecuador), or United Nations (e.g., Timor-Leste) mandate. The question of who establishes the commission (or to what political institution it is accountable) is not immediately relevant for determining procedural autonomy. Rather, a truth commission’s mark of distinction is that its operation and final report are independent of the authority that establishes it. Mark Freeman is right to point out that truth commission autonomy is analogous to judicial autonomy in that appointment by the state does not undermine the independence of a body as long as it enjoys operational autonomy.12

The crucial test for autonomy is whether or not the political decision makers alter the content of the final report, either during or after the commission process. Most truth commissions defend their autonomy in the face of political encroachment. For example, the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) ensured that neither the governing African National Congress nor any other political actor succeeded in revising the content of its final report, despite the fact that many of the findings had delegitimizing consequences for the postapartheid government and the opposition.13 A contrasting example is the final report of Uruguay’s 1985 parliamentary commission of inquiry called the Investigative Commission on the Situation of Disappeared People and Its Causes. A commentator writes: “the final statement of the commission on the disappeared was negotiated between the participating parties,” that is to say, between members of the parliament representing different political parties.14 Thus, the South African commission qualifies as a truth commission, while the Uruguayan one does not. Needless to say, the commissioners and the staff, aware of the political stakes involved, take into account the reactions of powerful actors. In other words, autonomy is not isolation: the criterion of autonomy asks for freedom from direct political intervention, but not inattentiveness to the political context.

Truth commission autonomy introduces a caveat that concerns the professional profile and prior political activism of commissioners. Commissions usually try to avoid appearing like partisan bodies, which separates them from bipartisan or multiparty parliamentary commissions, like Uruguay’s 1985 Investigative Commission or Germany’s 1992 Commission of Inquiry for the Assessment of History and Consequences of the SED Dictatorship. Individual merit (a combination of professional standing and moral impeccability) is emphasized as the fundamental criterion for designating commissioners. Nevertheless, it is important to note that most commissioners come from a background of political activism or public service. Notable exceptions notwithstanding, politicians and bureaucrats usually resign government jobs before taking part in the commission process.15 In other words, the principles of nonpartisanship and individual merit guide all truth commissions, but in each process the principles are interpreted differently.

Fifth, truth commissions are official in character, in the sense that a state institution or an international organization authorizes the commissioners to undertake the truth-finding task. Nongovernmental fact-finding bodies are not truth commissions. It cannot be denied that efforts to come to terms with the legacy of political violence usually originate with civil society actors, prior to the establishment of official commissions. For example, the meticulous documentation of abuses by human rights groups in Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, and Peru under high-risk conditions laid the groundwork for truth commissions in those countries, while similar civil society projects in other Latin American countries, like Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay, contributed to the preservation of historical memory when governments refused to establish official truth commissions. The enormous impact of some civil society initiatives cannot be overemphasized: as the “Never Again” reports in Uruguay and Brazil suggest, nonofficial investigations can substitute for the lack of political initiative in addressing the public demand for the truth concerning human rights violations. In procedural terms, however, civil society investigations are not truth commissions because they lack an official mandate, and their findings do not carry the promise of official endorsement.

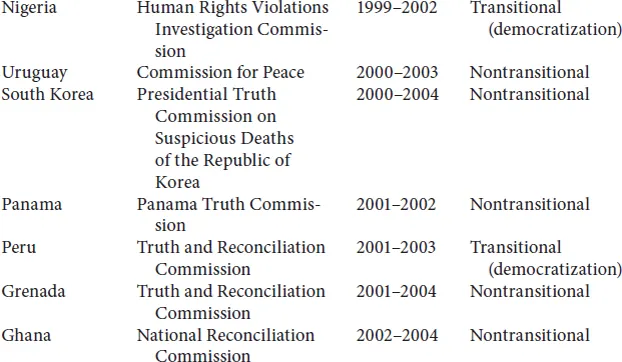

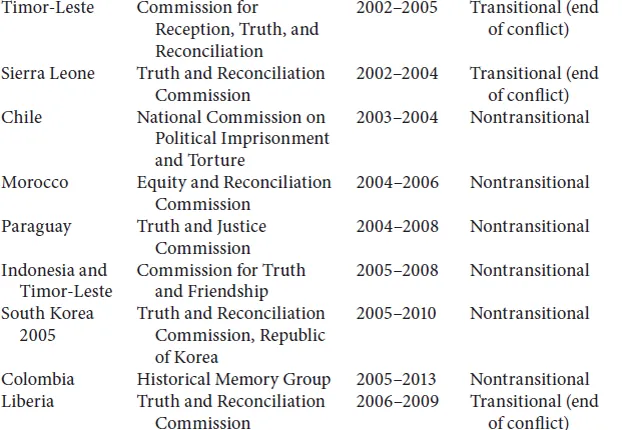

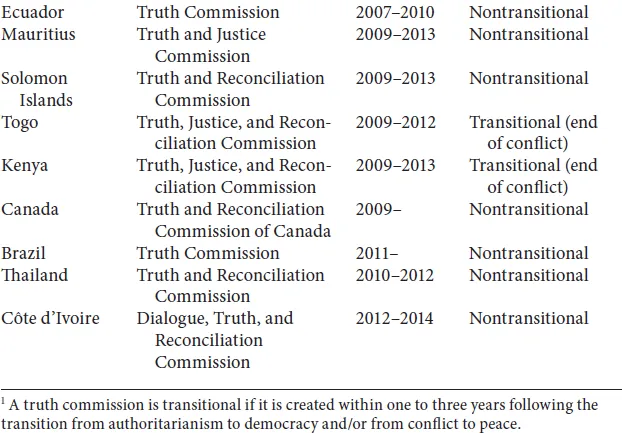

Table 1 presents a list of truth commissions. Incomplete truth commissions, as well as parliamentary commissions of inquiry are excluded from this list in light of the criteria explained above. As of late 2014 there were thirty-three national truth commissions that had completed their work, two ongoing commissions, and five incomplete commissions that had disbanded without producing a final report. Of the completed commissions, seventeen were established during transitions from authoritarianism to democracy and/or from internal conflict to peace,16 while sixteen were non-transitional. Both of the ongoing commissions are nontransitional.

Table 1. Complete and Ongoing Truth Commissions

Incomplete Truth Commissions

Not all truth commissions succeed in producing a publicly available record of human rights violations. Some commissions fail to publish a final report, and in other cases social and political actors’ attempts to establish a truth commission fail in the first place. Failed attempts should not be named “truth commissions” in the interest of sustaining conceptual clarity. Rather, the processes leading up to their failure should be addressed in further research. Those truth commissions that were disbanded before publishing a final report should be called “incomplete truth commissions.” The existence of an incomplete commission means that the idea of a truth commission had considerable societal appeal, which had to be acknowledged by decision makers, but that the project fell short of realization for reasons that may shed light on that country’s politics around postconflict truth and justice.

Five countries set up panels that could not publicize their findings and recommendations at all. In Bolivia (1982), Ecuador (1996), and the former Yugoslavia (2001), the commissions disbanded before completing their job; in Uganda (1974) and Zimbabwe (1983), the final reports, presented to presidents who had no interest in promoting human rights accountability, did not see the light of day. Below I provide a brief description of how and why these commission attempts were frustrated, in chronological order.

Although many governments that sponsored truth commissions were reluctant to commit to the goals of truth finding and justice, arguably none was as uncommitted to the human rights norm as Idi A...