![]()

I. Hugh of St. Victor, The Three Best Memory Aids for Learning History

translated by Mary Carruthers

Hugh of St. Victor was one of the major intellectual figures of the first half of the twelfth century. He taught in the school of St. Victor, a reformed abbey of Augustinian canons in Paris. In the course of his pedagogical career, he composed many dozens of works of theology and exegesis, along with significant works in disciplines ranging from history and grammar to geometry and cartography. His writings were particularly substantial in the realms of mystical theology and exegesis, where his students in the convent of St. Victor, Richard and Andrew, continued his work. His works are found in some 2500 manuscripts, bearing testimony to his influence outside St. Victor. He died in Paris in 1141.

In the Latin title given in the manuscripts to this brief school treatise, “[liber] de tribus maximis circumstantiis gestorum,” the word circumstantia is used in a technical sense and derives from a standard medieval pedagogy that Hugh also used to introduce his commentaries on various books of the Bible. The method goes back as far as Gregory the Great and Bede, who spoke of there being three circumstantiae necessary to know about each of the biblical books, namely,persona, locus, and tempus–“who wrote it, where, when, and for what occasion.” Such circumstantiae were long a part of the ancient pedagogy of rhetoric and were taught as a basic tool of invention, for finding, focusing, and delimiting one’s subject.

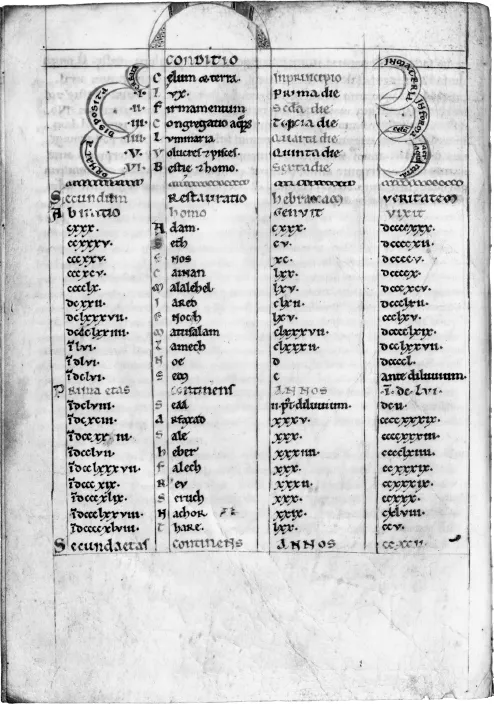

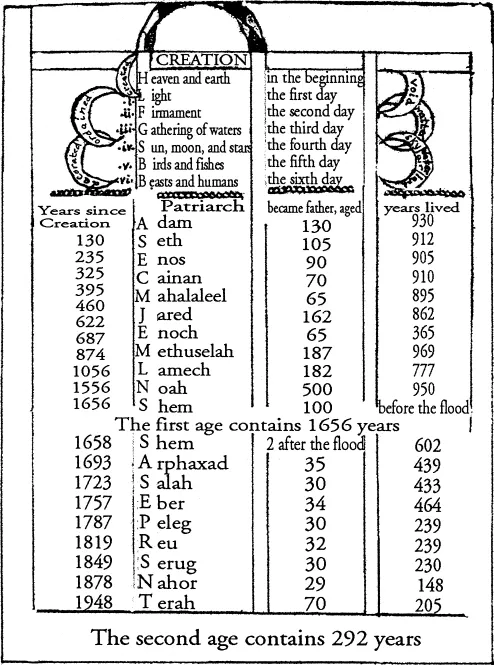

Hugh of St.Victor has adapted this technique for his novices beginning their Bible studies: to learn the history securely, one needs first to memorize persons, places, and dates.These circumstantiae are the mnemonically functioning headings Hugh describes in the last paragraphs of his introduction, exactly as he wants them to be put away in the strongbox of his students’ memories, and for which he provided a diagram (Figures 1.1, 1.2). The principle of divisio, that the memory be stored in a number of “chunks,” each of a size equivalent to the limit of immediate memory, is here clearly demonstrated. Each psalm is first reduced to its incipit, and then this initial phrase is attached by meditation to the numbers of the Psalms in order. One next proceeds to add to one’s memory the rest of each psalm’s text, in the manner Hugh then describes. The “single glance” of memory–what you can take in with one look of your mind’s eye – is the medieval memory-writer’s term closest to our concept of “short-term memory.” Though this is generally somewhere between four and eight things, notice how Hugh stresses that each of his students will have to observe for himself just how long a textual chunk is appropriate to his own mental glance. It is also noteworthy that the examples Hugh cites with respect to the first chunk of the first three psalms are quite short.

This brief work was composed as a preface to a chronology of biblical history Hugh compiled for the student-novices at St. Victor. The last three paragraphs of the treatise refer directly to the diagram Hugh devised for his chronology.What is interesting about his language in these paragraphs is the picture it is designed to paint in the minds of his students. Though far less elaborate than the diagram in A Little Book About Constructing Noah’s Ark, it nonetheless stresses numbers, and expounds step-by-step the order of creation, put in place by God in nature and disposed by the students in the places of their mental diagram. And as God usefully ornaments his creation, so the memory structure needs to be decorated usefully in order to achieve the mnemonic task properly. The drawing accompanying this translation is derived from that in the manuscript on which the standard edited text is based, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS. lat. 15009, a late twelfth-century manuscript from the library of St. Victor itself.

SOURCE: Revised from Carruthers, Book of Memory, 261–66; see esp. 80–85 for a discussion of the techniques described.Translated from the edition of William M.Green, “De tribus maximis circumstantiis gestorum,” Speculum 18 (1943): 484–93. Two typographical errors in that text have been corrected: ornatem (for ornatam), p. 490.24, and pituit (for potuit), p. 490.40.

FURTHER READING: The work was discussed as a memory art by Grover A. Zinn, Jr., “Hugh of St. Victor and the Art of Memory,” Viator 5 (1974): 211–34. The standard discussion and catalogue of all the manuscripts of Hugh of St. Victor’s work (which in the absence of a comprehensive modern critical edition remains an essential tool for all students of his works) is Rudolph Goy, Die Überlieferung der Werke Hugos von St. Viktor (Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann, 1976).

–Mary Carruthers

Child, knowledge is a treasury and your heart is its strongbox. As you study all of knowledge, you store up for yourselves good treasures, immortal treasures, incorruptible treasures, which never decay nor lose the beauty of their brightness. In the treasure house of wisdom are various sorts of wealth, and many filing-places in the storehouse of your heart. In one place is put gold, in another silver, in another precious jewels. Their orderly arrangement is clarity of knowledge. Dispose and separate each single thing into its own place, this into its and that into its, so that you may know what has been placed here and what there. Confusion is the mother of ignorance and for-getfulness, but orderly arrangement illuminates the intelligence and secures memory.

You see how a money-changer who has unsorted coins divides his one pouch into several compartments, just as a cloister embraces many separate cells inside. Then, having sorted the coins and separated out each type of money in turn, he puts them all to be kept in their proper places, so that the distinctiveness of his compartments may keep the assortment of his materials from getting mixed up, just as it supports their separation.1 Additionally, you observe in his display of money-changing, how his ready hand without faltering follows wherever the commanding nod of a customer has caused it to extend, and quickly, without delay, it brings into the open, separately and without confusion, everything that he either may have wanted to receive or promised to give out. And it would provide onlookers with a spectacle silly and absurd enough, if, while one and the same money-bag should pour forth so many varieties without muddle, this same bag, its mouth being opened, should not display on its inside an equivalent number of separate compartments. And so this particular separation into distinct places, which I have described, at one and the same time eliminates for the onlookers any mystery in the action, and, for those doing it, an obstacle to their ability to perform it.

Figure 1.1. Paris, BNF MS lat.15009, fol. 3v. Photo: Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Figure 1.2. “The Beginning of History,” from Hugh of St. Victor’s Chronicon. Drawing by Mary Carruthers.

Now as we just said by way of preface, a classifying-system for material makes it manifest to the mind. Truly such a display of matters both illuminates the soul when it perceives them, and confirms them in memory. Return, therefore, child, to your heart and consider how you should dispose and collect in it the precious treasures of wisdom, so that you may learn about its individual repositories, and when for safekeeping you place something in them, dispose it in such an order that when your reason asks for it, you are easily able to find it by means of your memory and understand it by means of your intellect, and bring it forth by means of your eloquence. I am going to propose to you a particular method for such classification.

Matters that are learned are classified in the memory in three ways; by number, location, and occasion. Thus all the things which you may have heard you will both readily capture in your intellect and retain for a long time in your memory, if you have learned to classify them according to these three categories. I will demonstrate one at a time the manner in which each should be used.

The first means of classifying is by number. Learn to construct in your mind a line [of numbers] numbered from one on, in however long a sequence you want, extended as it were before the eyes of your mind. When you hear any number at all called out, become accustomed to quickly turning your mind there [on your mental line] where its sum is enclosed, as though to that specific point at which in full this number is completed. For example, when you hear ten, think of the tenth place, or when twelve, think of the twelfth, so that you conceive of the whole according to its outer extent [along the line], and likewise for the other [numbers]. Make this conception and this way of imagining it practiced and habitual, so that you conceive of the limit and extent of all numbers visually, just as though [they were] placed in particular places. And listen to how this mental visualization may be useful for learning.

Suppose for example that I wish to learn the Psalter word for word by heart. I proceed thus: first I consider how many psalms there are. There are 150. I learn them all in order so that I know which is the first, which the second, which the third, and so on. I then place them all by order in my heart along my [mental] numerical line, and one at a time I designate them to the seats where they are disposed in the grid, while at the same time, accompanied by voicing or cogitation, I listen and observe closely until each becomes to me of a size equivalent to one glance of my memory: “Blessed is the man,” with respect to the first psalm; “Why have the gentiles raged,” with respect to the second; “Why, O Lord, are they multiplied,” with respect to the third; this [much] is kept in the first, second, and third compartments. And then I imprint the result of my mental effort by the vigilant concentration of my heart so that, when asked, without hesitation I may answer, either in forward order, or by skipping one or several, or in reverse order and recited backward according to my completely mastered scheme of places, what is the first, what the second, what indeed the 27th, the 48th, or whatever psalm it should be. In this manner [disputants] demonstrate [that] the Scriptures confirm their own arguments when, as they are about to use the authority of some one psalm, they say this is written in the 63rd, this in the 75th, or whatever other psalm, fetching forth for reference not its name but its number. For surely, you do not think that those who wish to cite some one of the psalms have turned over the manuscript pages, so that starting their count from the beginning they could figure out what number in the series of psalms each might have? The labor in such a task would be too great. Therefore they have in their heart a powerful mental device, and they have retained it in memory, for they have learned the number and the order of each single item in the series.

Having learned the Psalms [as a whole], I then devise the same sort of scheme for each separate psalm, starting with the beginning words of the verses just as I did for the whole Psalter starting with the first words of the psalms, and I can thereafter easily retain in my heart the whole series one verse at a time; first by dividing and marking off the book by [whole] psalms and then each psalm by verses, I have reduced a large amount of material to such conciseness and brevity. And this [method] in fact can readily be seen in the psalms or in other books containing obvious divisions. When however the reading is in an unbroken series, it is necessary to do this artificially, so that, to be sure according to the convenience of the reader, [at those places] where it seems [to him] most suitable, first the whole piece is divided into a fixed number of sections, and these again into others, these into yet others, until the whole length of material is so parceled up that the mind can easily retain it in single units. For the memory always rejoices in both brevity of length and paucity of number, and therefore it is necessary, when the sequence of your reading tends toward length, that it first be divided into a few units, so that what the mind could not comprehend in a single expanse it can comprehend at least in a number, and again, when later the more moderate number of items is subdivided into many, it may be aided in each case by the principle of paucity or brevity.

So you see the value to learning a numerical division-scheme; now see and consider of what value for the same thing is the classification-system according to location. Have you never noticed how a boy has greater difficulty impressing upon his memory what he has read if he often changes his copy [of a text] between readings? Why should this be unless it is because, when the image-receiving power of the heart is directed outward through the senses into so many shapes from diverse books, no specific image can remain within [the inner senses] by means of which a memory-image may be fixed? For when something is brought together to be fashioned into an image from all [the copies] indiscriminately, one superimposed upon another, and always the earlier being wiped away by later ones, nothing personal or familiar remains which by use and practice can be clearly possessed. Therefore it is a great value for fixing a memory-image that when we read books, we strive to impress on our memory through the power of forming our mental images not only the number and order of verses or ideas, but at the same time the color, shape, position, and placement of the letters, where we have seen this or that written, in what part, in what location (at the top, the middle, or the bottom) we saw it positioned, in what color we observed the trace of the letter or the ornamented surface of the parchment. Indeed I consider nothing so useful for stimulating the memory as this; that we also pay attention carefully to those circumstances of things which can occur accidentally and externally, so that, for example, together with the appearance and quality or location of the places in which we heard one thing or the other, we recall also the face and habits of the people from whom we learned this and that, and, if there are any, the things that accompany the performance of a certain activity. All these things indeed are rudimentary in nature, but of a sort beneficial for boys.

After the classifications by number and place follows the classification by occasions, that is: what was done earlier and what later, how much earlier and how much later, by how many years, months, days this precedes that and that follows this other. This classification is relevant in a situation when, according to the varying nature of the occasions on which we learned something, at a later time we may be able to recall to our mind a memory of the content, as we remember that one occasion was at night and another by day, one in winter another in summer, one in cloudy weather another in sunshine. All these things truly we have composed as a kind of prelude [to our learning], providing the basics to children, lest we, disdaining these most basic elements of our studies, start little by little to ramble incoherently. Indeed the whole usefulness of education consists only in the memory of it, for just as having heard something does not profit one who cannot understand, likewise having understood is not valuable to one who either will not or cannot remember. Indeed it was profitable to have listened only insofar as it caused us to have understood, and to have understood insofar as it was retained. But these are as it were basics for knowledge, which, if they are firmly impressed in your memory, open up all the rest readily. We have written out this [list of names, dates, and places] for you in the following pages, disposed in the order in which we wish them to be implanted in your soul through memory, so that whatever afterward we build upon it may be firm.

All exposition of divine Scripture is drawn forth according to three senses: literal, allegorical, and tropological or moral. The literal is the narrative of history, expressed in the basic meaning of the letter. Allegory is when by means of this event in the story, which we find in the literal meaning, another action is signified, belonging to past or present or future time. Tropology is when in that action which we hear was done, we recognize what we should be doing. Whence it rightly receives the name “tropology,” that is, converted speech or replicated discourse, for without a doubt we turn the word of a story about others to our own instruction when, having read of the deeds of others, we conform our living to their example.

But now we have in hand history, as it were the foundation of all knowledge, the first to be laid out together in memory. But because, as we said, the memory delights in brevity, yet the events of history are nearly infinite, it is necessary for us, from among all of that material, to gather together a kind of brief summary–as it were the foundation of a foundation, that is a first foundation–which the soul can most easily comprehend and the memory retain. There are three matters on which the knowledge of past actions especially depends, that is, the persons who performed the deeds, the places in which they were performed, and the time at which they occurred. Whoever holds these three by memory in his soul will find that he has built a good foundation for himself, onto which he can assemble afterward anything by reading and lecture without difficulty and rapidly take it in and retain it for a long time. However, in so doing it is necessary to retain it in memory and by diligent retracing to have it customary and well known, so that his heart may be ready to put in place everything he has heard, and apply those classification techniques which he will have learned now, to all things that he may hear afterward by a suitable distribution according to their place, date, and person.

While [the circumstances of] tim...