![]()

PART A

Economic Growth

![]()

1

Fifty Years of Growth (and Lack Thereof): An Interpretation

REAL per capita income in the developing world grew at an average rate of 2.1 percent per annum during the four and a half decades between 1960 and 2004.1 This is a high growth rate by almost any standard. At this pace incomes double every 33 years, allowing each generation to enjoy a level of living standards that is twice as high as the previous generation’s. To provide some historical perspective on this performance, it is worth noting that Britain’s per capita GDP grew at a mere 1.3 percent per annum during its period of economic supremacy in the middle of the nineteenth century (1820–70) and that the United States grew at only 1.8 percent during the half century before World War I when it overtook Britain as the world’s economic leader (Maddison 2001, table B-22, 265). Moreover, with few exceptions, economic growth in the last few decades has been accompanied by significant improvements in social indicators such as literacy, infant mortality, and life expectation.2 So on balance the recent growth record looks quite impressive.

However, since the rich countries themselves grew at a very rapid clip of 2.5 percent during the period 1960–2004, few developing countries consistently managed to close the economic gap between them and the advanced nations. As figure 1.1 indicates, the countries of East and Southeast Asia constitute the sole exception. Excluding China, this region experienced pretty consistent per capita GDP growth of 3.7 percent over 1960–2004. Despite the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98 (which shows as a slight dip in figure 1.1), countries such as South Korea, Thailand, and Malaysia ended the century with productivity levels that stood significantly closer to those enjoyed in the advanced countries.

Fig. 1.1. GDP per capita by country groupings (in 2000 US$) Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Elsewhere, the pattern of economic performance has varied greatly across different time periods. China has been a major success story since the late 1970s, experiencing a stupendous growth rate of 8.0 percent since 1978. Less spectacularly, India has roughly doubled its growth rate since the early 1980s, pulling South Asia’s growth rate up to 3.3 percent in 1980–2000 from 1.1 percent in 1960–1980. The experience in other parts of the world was the mirror image of these Asian growth take-offs. Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa both experienced robust economic growth prior to the late 1970s and early 1980s—2.9 percent and 2.2 percent respectively—but then lost ground subsequently in dramatic fashion. Latin America’s growth rate collapsed in the “lost decade” of the 1980s, and has remained anemic despite some recovery in the 1990s. Africa’s economic decline, which began in the second half of the 1970s, continued throughout much of the 1990s and has been aggravated by the onset of HIV/AIDS and other public-health challenges. Measures of total factor productivity run parallel to these trends in per capita output (see, for example, Bosworth and Collins 2003).

Hence the aggregate picture hides tremendous variety in growth performance, both geographically and temporally. We have high-growth countries and low-growth countries; countries that have grown rapidly throughout, and countries that have experienced growth spurts for a decade or two; countries that took off around 1980 and countries whose growth collapsed around 1980.

This chapter is devoted to the question, what do we learn about growth strategies from this rich and diverse experience? By growth strategies I refer to economic policies and institutional arrangements aimed at achieving economic convergence with the living standards prevailing in advanced countries. My emphasis will be less on the relationship between specific policies and economic growth—the stock-in-trade of cross-national growth empirics—and more on developing a broad understanding of the contours of successful strategies. Hence my account harks back to an earlier generation of studies that distilled operational lessons from the observed growth experience, such as Albert Hirschman’s The Strategy of Economic Development (1958), Alexander Gerschenkron’s Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective (1962), and Walt Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth (1965). This chapter follows an unashamedly inductive approach in this tradition.

A key theme in these works, as well as in the present analysis, is that growth-promoting policies tend to be context specific. We are able to make only a limited number of generalizations on the effects on growth, say, of liberalizing the trade regime, opening up the financial system, or building more schools. As I will stress throughout this book, the experience of the last two decades has frustrated the expectations of policy advisors who thought we had a good fix on the policies that promote growth. And despite a voluminous literature, cross-national growth regressions ultimately do not provide us with much reliable and unambiguous evidence on such operational matters.3 An alternative approach, the one I adopt here, is to shift our focus to a higher level of generality and to examine the broad design principles of successful growth strategies. This entails zooming away from the individual building blocks and concentrating on how they are put together.

The chapter revolves around two key arguments. One is that neoclassical economic analysis is a lot more flexible than its practitioners in the policy domain have generally given it credit for. In particular, first-order economic principles—protection of property rights, contract enforcement, market-based competition, appropriate incentives, sound money, debt sustainability—do not map into unique policy packages. Good institutions are those that deliver these first-order principles effectively. There is no unique correspondence between the functions that good institutions perform and the form that such institutions take. Reformers have substantial room for creatively packaging these principles into institutional designs that are sensitive to local constraints and take advantage of local opportunities. Successful countries are those that have used this room wisely.

The second argument is that igniting economic growth and sustaining it are somewhat different enterprises. The former generally requires a limited range of (often unconventional) reforms that need not overly tax the institutional capacity of the economy. The latter challenge is in many ways harder, as it requires constructing a sound institutional underpinning to maintain productive dynamism and endow the economy with resilience to shocks over the longer term. The good news is that this institutional infrastructure does not have to be constructed overnight. Ignoring the distinction between these two tasks—starting and sustaining growth—leaves reformers saddled with impossibly ambitious, undifferentiated, and impractical policy agendas.

The plan for the chapter is as follows. The next section sets the stage by evaluating the standard recipes for economic growth in light of recent economic performance. The third section develops the argument that sound economic principles do not map into unique institutional arrangements and reform strategies. The fourth section reinterprets recent growth experience using the conceptual framework of the previous section. The fifth section discusses a two-pronged growth strategy that differentiates between the challenges of igniting growth and the challenges of sustaining it. Concluding remarks are presented in the final section.

WHAT WE KNOW THAT (POSSIBLY) AIN’T SO

Development policy has always been subject to fads and fashions. During the 1950s and 1960s, “big push,” planning, and import-substitution were the rallying cries of economic reformers in poor nations. These ideas lost ground during the 1970s to more market-oriented views that emphasized the role of the price system and an outward orientation.4 By the late 1980s a remarkable convergence of views had developed around a set of policy principles that John Williamson (1990) infelicitously termed the “Washington Consensus.” These principles remain at the heart of conventional understanding of a desirable policy framework for economic growth, even though they have been greatly embellished and expanded in the years since.

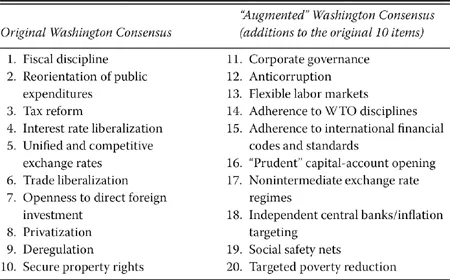

The left panel in table 1.1 shows Williamson’s original list, which focused on fiscal discipline, “competitive” currencies, trade and financial liberalization, privatization and deregulation. These were perceived to be the key elements of what Krugman (1995, 29) has called the “Victorian virtue in economic policy,” namely “free markets and sound money.”

TABLE 1.1

Rules of Good Behavior for Promoting Economic Growth

Toward the end of the 1990s, this list was augmented in the thinking of multilateral agencies and policy economists with a series of so-called second-generation reforms that were more institutional in nature and targeted at problems of “good governance.” A complete inventory of these Washington Consensus–plus reforms would take too much space, and in any case the precise listing differs from source to source. 5 I have shown a representative sample of 10 items (to preserve the symmetry with the original Washington Consensus) in the right panel of table 1.1. They range from anticorruption and corporate governance to “flexible” labor markets and social safety nets.

The perceived need for second-generation reforms arose from a combination of sources. First, there was growing recognition that market-oriented policies might be inadequate without more serious institutional transformation, in areas ranging from the bureaucracy to labor markets. For example, trade liberalization will not reallocate an economy’s resources appropriately if the labor markets are “rigid” or insufficiently “flexible.” Second, there was a concern that financial liberalization might lead to crises and excessive volatility in the absence of a more carefully delineated macroeconomic framework and improved prudential regulation. Hence arose the focus on nonintermediate exchange-rate regimes, central bank independence, and adherence to international financial codes and standards. Finally, in response to the complaint that the Washington Consensus represented a trickle-down approach to poverty, the policy framework was augmented with social policies and antipoverty programs.

It is probably fair to say that a list along the lines of table 1.1 captures in broad brushstrokes mainstream post–Washington Consensus thinking on the key elements of a growth program. How does such a list fare when held against the light of contemporary growth experience? Imagine that we gave table 1.1 to an intelligent Martian and asked him to match the growth record displayed in figure 1.1 with the expectations that the list generates. How successful would he be in identifying which of the regions adopted the standard policy agenda and which did not?

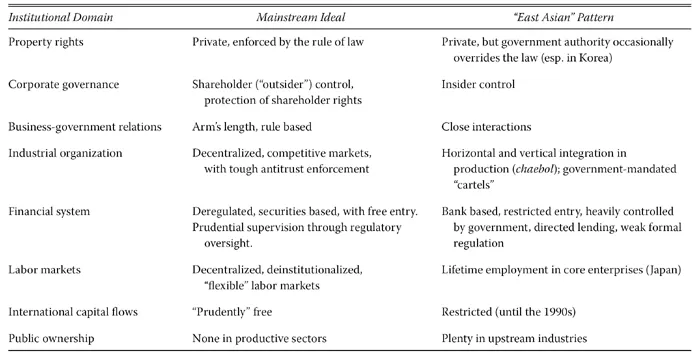

Consider first the high-performing East Asian countries. Since this region is the only one that has done consistently well since the early 1960s, the Martian would reasonably guess that there is a high degree of correspondence between the region’s policies and the list in table 1.1. But he would be at best half right. South Korea’s and Taiwan’s growth policies, to take two important illustrations, exhibit significant departures from the mainstream consensus. Neither country undertook significant deregulation or liberalization of its trade and financial systems well into the 1980s. Far from privatizing, they both relied heavily on public enterprises. South Korea did not even welcome direct foreign investment. And both countries deployed an extensive set of industrial policies that took the form of directed credit, trade protection, export subsidization, tax incentives, and other nonuniform interventions. Using the minimal scorecard of the original Washington Consensus (left panel of table 1.2), the Martian would award South Korea a grade of 5 (out of 10) and Taiwan perhaps a 6 (Rodrik 1996a).

The gap between the East Asian “model” and the more demanding institutional requirements shown in the right panel of table 1.1 is, if anything, even larger. I provide a schematic comparison between the mainstream “ideal” and the East Asian reality in table 1.2 for a number of different institutional domains, such as corporate governance, financial markets, business-government relationships, and public ownership. Looking at these discrepancies, the Martian might well conclude that South Korea, Taiwan, and (before them) Japan stood little chance to develop. Indeed, so strong were the East Asian anomalies that when the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98 struck, many observers attributed the crisis to the moral hazard, “cronyism,” and other problems created by East Asian–style institutions (see MacLean 1999; Frankel 2000a).

The Martian would also be led astray by China’s boom since the late 1970s and by India’s less phenomenal, but still significant growth pickup since the early 1980s. While both of these countries have transformed their attitudes toward markets and private enterprise during this period, their policy frameworks bear very little resemblance to what is described in table 1.1. India deregulated its policy regime slowly and undertook very little privatization. Its trade regime remained heavily restricted late into the 1990s. China did not even adopt a private property rights regime, and it merely appended a market system to the scaffolding of a planned economy (as discussed further below). It is hardly an exaggeration to say that had the Chinese economy stagnated in the last couple of decades, the Martian would be in a better position to rationalize it using the policy guidance provided in table 1.1 than he is to explain China’s actual performance.6

TABLE 1.2

East Asian Anomalies

The Martian would be puzzled that the region that made the most determined attempt at remaking itself in the image of table 1.1, namely Latin America, has reaped so little growth benefit out of it. Countries such as Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru did more liberalization, deregulation, and privatization in the course of a few years than East Asian countries have done in four decades. Figure 1.2 shows an index of structural reform for these and other Latin American countries, taken from Lora (2001a). The index measures on a scale from 0 to 1 the extent of trade and financial liberalization, tax reform, privatization, and labor-market reform undertaken. The regional average for the index rises steadily from 0.34 in 1985 to 0.58 in 1999. Yet the striking fact from figure 1.1 is that Latin America’s growth rate has remained a fraction of its pre-1980 level. The Martian would be at a loss to explain why growth is now lower given that the quality of Latin America’s policies, as judged by the requirements in table 1.1, have improved so much.7 A similar puzzle, perhaps of a smaller magnitude, arises with respect to Afri...