![]()

1 THE INVISIBLE HOOK

Charybdis herself must have spat them into the sea. They committed “a Crime so odious and horrid in all its Circumstances, that those who have treated on that Subject have been at a loss for Words and Terms to stamp a sufficient Ignominy upon it.” Their contemporaries called them “Sea-monsters,” “Hell-Hounds,” and “Robbers, Opposers and Violators of all Laws, Humane and Divine.” Some believed they were “Devils incarnate.” Others suspected they were “Children of the Wicked One” himself. “Danger lurked in their very Smiles.”

For decades they terrorized the briny deep, inspiring fear in the world’s most powerful governments. The law branded them hostes humani generis—“a sort of People who may be truly called Enemies to Mankind”—and accused them of aiming to “Subvert and Extinguish the Natural and Civil Rights” of humanity. They “declared War against all the World” and waged it in earnest. Motley, murderous, and seemingly maniacal, their mystique is matched only by our fascination with their fantastic way of life. “These Men, whom we term, and not without Reason, the Scandal of human Nature, who were abandoned to all Vice, and lived by Rapine” left a mark on the world that remains nearly three centuries after they left it. They are the pirates, history’s most notorious criminals, and this is the story of the hidden force that propelled them—the invisible hook.

Adam Smith, Meet “Captain Hook”

In 1776 Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith published a landmark treatise that launched the study of modern economics. Smith titled his book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. In it, he described the most central idea to economics, which he called the “invisible hand.” The invisible hand is the hidden force that guides economic cooperation. According to Smith, people are self-interested; they’re interested in doing what’s best for them. However, often times, to do what’s best for them, people must also do what’s best for others. The reason for this is straightforward. Most of us can only serve our self-interests by cooperating with others. We can achieve very few of our self-interested goals, from securing our next meal to acquiring our next pair of shoes, in isolation. Just think about how many skills you’d need to master and how much time you’d require if you had to produce your own milk or fashion your own coat, let alone manufacture your own car.

Because of this, Smith observed, in seeking to satisfy our own interests, we’re led, “as if by an invisible hand,” to serve others’ interests too. Serving others’ interests gets them to cooperate with us, serving our own. The milk producer, for example, must offer the best milk at the lowest price possible to serve his self-interest, which is making money. Indirectly he serves his customers’ self-interest, which is acquiring cheap, high-quality milk. And on the other side of this, the milk producers’ customers, in their capacity as producers of whatever they sell, must offer the lowest price and highest quality to their customers, and so on. The result is a group of self-interest seekers, each narrowly focused on themselves but also unwittingly focused on assisting others.

Smith’s invisible hand is as true for criminals as it is for anyone else. Although criminals direct their cooperation at someone else’s loss, if they desire to move beyond one-man mug jobs, they must also cooperate with others to satisfy their self-interests. A one-man pirate “crew,” for example, wouldn’t have gotten far. To take the massive hauls they aimed at, pirates had to cooperate with many other sea dogs. The mystery is how such a shifty “parcel of rogues” managed to pull this off. And the key to unlocking this mystery is the invisible hook—the piratical analog to Smith’s invisible hand that describes how pirate self-interest seeking led to cooperation among sea bandits, which this book explores.

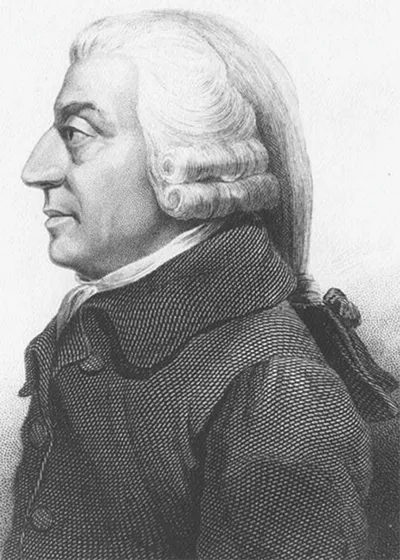

FIGURE 1.1. Adam Smith: Father of modern economics and the “invisible hand.” From Charles Coquelin, Dictionnaire de l’économie politique, 1854.

The invisible hook differs from the invisible hand in several respects. First, the invisible hook considers criminal self-interest’s effect on cooperation in pirate society. It’s concerned with how criminal social groups work. The invisible hand, in contrast, considers traditional consumer and producer self-interests’ effects on cooperation in the marketplace. It’s concerned with how legitimate markets work. If the invisible hand examines the hidden order behind the metaphorical “anarchy of the market,” the invisible hook examines the hidden order behind the literal anarchy of pirates.

Second, unlike traditional economic actors guided by the invisible hand, pirates weren’t primarily in the business of selling anything. They therefore didn’t have customers they needed to satisfy. Further, piratical self-interest seeking didn’t benefit wider society, as traditional economic actors’ self-interest seeking does. In their pursuit of profits, businessmen, for example, improve our standards of living—they make products that make our lives better. Pirates, in contrast, thrived parasitically off others’ production. Thus pirates didn’t benefit society by creating wealth; they harmed society by siphoning existing wealth off for themselves.

Despite these differences, pirates, like everyone else, had to cooperate to make their ventures successful. And it was self-interest seeking that led them to do so. This critical feature, common to pirates and the members of “legitimate” society, is what fastens the invisible hook to the invisible hand.

The Invisible Hook applies the “economic way of thinking” to pirates. This way of thinking is grounded in a few straightforward assumptions. First, individuals are self-interested. This doesn’t mean they never care about anyone other than themselves. It just means most of us, most of the time, are more interested in benefiting ourselves and those closest to us than we’re interested in benefiting others. Second, individuals are rational. This doesn’t mean they’re robots or infallible. It just means individuals try to achieve their self-interested goals in the best ways they know how. Third, individuals respond to incentives. When the cost of an activity rises, individuals do less of it. When the cost of an activity falls, they do more of it. The reverse is true for the benefit of an activity. When the benefit of an activity rises, we do more it. When the benefit falls, we do less of it. In short, people try to avoid costs and capture benefits.

Economists call this model of individual decision making “rational choice.” The rational choice framework not only applies to “normal” individuals engaged in “regular” behavior. It also applies to abnormal individuals engaged in unusual behavior. In particular, it applies to pirates. Pirates satisfied each of the assumptions of the economic way of thinking described above. Pirates, for instance, were self-interested. Material concerns gave birth to pirates and profit strongly motivated them. Contrary to pop-culture depictions, pirates were also highly rational. As we’ll examine later in this book, pirates devised ingenious practices—some they’re infamous for—to circumvent costs that threatened to eat into their profits and increase the revenue of their plundering expeditions. Pirates also responded to incentives. When the law made it riskier (and thus costlier) to be a pirate, pirates devised clever ways to offset this risk.

When pirates offered crew members rewards for superlative pirating, crew members worked harder to keep a lookout for the next big prize, and so on.

It’s not just that economics can be applied to pirates. Rational choice is the only way to truly understand flamboyant, bizarre, and downright shocking pirate practices. Why, for example, did pirates fly flags with skulls and crossbones? Why did they brutally torture some captives? How were pirates successful? And why did they create “pirate codes”? The answers to these questions lie in the hidden economics of pirates, which only the rational choice framework can reveal. History supplies the “raw material” that poses these questions. Economics supplies the analytical “lens” for finding the answers.

When we view pirates through this lens, their seemingly unusual behavior becomes quite usual. Strange pirate behavior resulted from pirates rationally responding to the unusual economic context they operated in—which generated unusual costs and benefits—not from some inherent strangeness of pirates themselves. As remaining chapters of this book illustrate, a pirate ship more closely resembled a Fortune 500 company than the society of savage schoolchildren depicted in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Peglegs and parrots aside, in the end, piracy was a business. It was a criminal business, but a business nonetheless, and deserves to be examined in this light.

Avast, Ye Scurvy Dogs

Many discussions of pirates use the terms pirates, buccaneers, privateers, and corsairs interchangeably. There’s a reason for this; all were kinds of sea bandits. But each variety of sea bandit was different. Pure pirates were total outlaws. They attacked merchant ships indiscriminately for their own gain. Richard Allein, attorney general of South Carolina, described them this way: “Pirates prey upon all Mankind, and their own Species and Fellow-Creatures, without Distinction of Nations or Religions.” Eighteenth-century sea bandits were predominantly this ilk.

Privateers, in contrast, were state-sanctioned sea robbers. Governments commissioned them to attack and seize enemy nations’ merchant ships during war. Privateers, then, weren’t pirates at all; they had government backing. Similarly, governments sanctioned corsairs’ plunder. The difference is corsairs targeted shipping on the basis of religion. The Barbary corsairs of the North African coast, for instance, attacked ships from Christendom. However, there were Christian corsairs as well, such as the Knights of Malta. This book’s discussion primarily excludes privateers and corsairs since they typically weren’t outlaws.

Buccaneers, in contrast, typically were. The original buccaneers were French hunters living on Hispaniola, modern-day Haiti, in the early seventeenth century. Although they mostly hunted wild game, they weren’t opposed to the occasional act of piracy either. In 1630 the buccaneers migrated to Tortuga, a tiny, turtle-shaped island off Hispaniola, which soon attracted English and Dutch rabble as well. Spain officially possessed Hispaniola and Tortuga and wasn’t fond of the outlaw settlers. In an effort to drive them away, the Spanish government wiped out the wild animals the hunters thrived on. Instead of leaving, however, the buccaneers began hunting a different sort of game: Spanish shipping.

In 1655 England wrested Jamaica from the Spaniards and encouraged the buccaneers to settle there as a defense against the island’s recapture. Buccaneers spent much of their time preying on Spanish ships laden with gold and other cargo sailing between the mother country and Spain’s possessions in the Americas. Many of these attacks were outright piracy. But many others were not. Eager to break Spain’s monopoly on the New World under the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), England and France commissioned these sea rovers as privateers to harass Spain. “Buccaneering,” then, “was a peculiar blend of piracy and privateering in which the two elements were often indistinguishable.” However, since “the aims and means of [buccaneering] operations were clearly piratical,” it’s standard to treat the buccaneers as pirates, or at least protopirates, which I do in this book.

Although buccaneers weren’t pure pirates, they anticipated and influenced pure pirates’ organization in the early eighteenth century. Because of this, it’s important to draw on them at various points, as I do, throughout my discussion. The same is true of the Indian Ocean pirates operating from about 1690 to 1700. These sea rovers represent a bridge between the more privateerlike buccaneers and the total-outlaw pirates active from 1716 to 1726. In the late seventeenth century, the Indian Ocean pirates, or “Red Sea Men” as their contemporaries sometimes called them, settled on Madagascar and its surrounding islands where they were well situated to prey on Moorish treasure fleets. For the most part, Indian Ocean pirates were pirates plain and simple. But some of them sailed under a veneer of legitimacy, which their successors abandoned completely. While this book covers pirates from about 1670 to 1730, it focuses on the final stage of the great age of piracy (1716–26) when men like Blackbeard, Bartholomew Roberts, and “Calico” Jack Rackam prowled the sea.

Jamaican governor Sir Nicholas Lawes described these sea scoundrels as “banditti of all nations.” A sample of seven hundred pirates active in the Caribbean between 1715 and 1725, for example, reveals that 35 percent were English, 25 percent were American, 20 percent were West Indian, 10 percent were Scottish, 8 percent were Welsh, and 2 percent were Swedish, Dutch, French, and Spanish. Others came from Portugal, Scandinavia, Greece, and East India.

The pirate population is hard to precisely measure but by all accounts was considerable. In 1717 the governor of Bermuda estimated “by a modest computation” that 1,000 pirates plied the seas. In 1718 a different official estimated the pirate population to be 2,000. In 1720 Jeremiah Dummer reported 3,000 active pirates to the Council of Trade and Plantations. And in Captain Charles Johnson suggested that 1,500 pirates haunted the Indian Ocean alone. Based on these reports and pirate historians’ estimates, in any one year between 1716 and roughly 1,000 to 2,000 sea bandits prowled the pirate-infested waters of the Caribbean, Atlantic Ocean, and Indian Ocean. This may not seem especially impressive. But when you put the pirate population in historical perspective it is. The Royal Navy, for example, employed an average of only 13,000 men in any one year between 1716 and 1726. In a good year, then, the pirate population was more than 15 percent of the navy’s. In 1680 the entire population of the North American colonies was less than 152,000. In fact, as late as 1790, when the first national census was taken, only twenty-four places in the United States had populations larger than 2,500.

Many pirates lived together on land bases, such as the one Woodes Rogers went to squelch at New Providence in the Bahamas in 1718. However, the most important unit of pirate society, and the strongest sense in which this society existed, was the polity aboard the pirate ship. Contrary to most people’s images of pirate crews, this polity was large. Based on figures from thirty-seven pirate ships between 1716 and 1726, the average crew had about 80 members. Several pirate crews were closer to 120, and crews of 150 to 200 weren’t uncommon. Captain Samuel Bellamy’s pirate crew, for example, consisted of “200 brisk Men of several Nations.” Other crews were even bigger than this. Blackbeard’s crew aboard Queen Anne’s Revenge was 300-men strong. In contrast, the average two-hundred-ton merchant ship in the early eighteenth century carried only 13 to 17 men.

Furthermore, some pirate crews were too large to fit in one ship. In this case they formed pirate squadrons. Captain Bartholomew Roberts, for example, commanded a squadron of four ships that carried 508 men. In addition, pirate crews sometimes joined for concerted plundering expeditions. The most impressive fleets of sea bandits belong to the buccaneers. Buccaneer Alexander Exquemelin, for example, records that Captain Morgan commanded a fleet of thirty-seven ships and 2,000 men, enough to attack communities on the Spanish Main. Elsewhere he refers to a group of buccaneers who “had a force of at least twenty vessels in quest of plunder.” Similarly, William Dampier records a pirating expedition that boasted ten ships and 960 men. Though their fleets weren’t as massive, eighteenth-century pirates also “cheerfully joined their Brethren in Iniquity” to engage in multicrew pirating expeditions.

Nearly all pirates had maritime backgrounds. Most had sailed on merchant ships, many were former privateers, and some had previously served—though not always willingly—in His or Her Majesty’s employ as navy seamen. Based on a sample of 169 early-eighteenth-century pirates Marcus Rediker compiled, the average pirate was 28.2 years old. The youngest pirate in this sample was only 14 and the oldest 50—ancient by eighteenth-century seafaring standards. Most pirates, however, were in their mid-twenties; 57 percent of those in Rediker’s sample were between 20 and 30. These data suggest a youthful pirate society with a few older, hopefully wiser, members and a few barely more than children. In addition to being very young, pirate society was also very male. We know of only four women active among eighteenth-century pirates. Pirate society was therefore energetic and testosterone filled, probably similar to a college fraternity only with peglegs, fewer teeth, and pistol dueling instead of wrestling to resolve disputes.

Yo Ho, Yo Ho, a Lucrative Life for Me

Pirate fiction portrays seamen as choosing piracy out of romantic, if misled, ideals about freedom, equality, and fraternity. While greater liberty, power sharing, and unity did prevail aboard pirate ships, as this book describes, these were piratical means, used to secure cooperation within pirates’ criminal organization, rather than piratical ends, as they’re often depicted.

This isn’t to say idyllic notions never motivated pirates. In his book, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, historian Marcus Rediker considers pirates in the larger context of eighteenth-century life at sea. Rediker persuasively argues that, in part, pirates acted as social revolutionaries in rebellion against the authoritative, exploitative, and rigidly hierarchical organization of pre–Industrial Revolution “state capitalism.” Others have suggested pirates may have acted partially out of concerns for greater racial and sexual equality.

Despite this, most sailors who became pirates did so for a more familiar reason: money. In this sense, though its popular treatment is riddled with myths, the traditional emphasis on “pirate treasure” is appropriate. Sea marauding could be a lucrative business. When, during war, would-be pirates could work as legalized sea bandits on privateers, they often did. During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), for instance, English sailors happily cruised on private men-of-war. Shipowners and government took a cut of privateers’ booty; but a successful voyage could still earn sailors a substantial sum. Britain’s Prize Act of 1708 sweetened the pot for these sailors by granting them and their shipowners the full value of their captures, government generously foregoing its share. Privateering was thus a desirable option when war was raging. But when it wasn’t, privateering commissions dried up. What was a sea dog to do?

One possibility was to seek employment in the Royal Navy. But at conflicts’ end the Royal Navy let sailors go. It wasn’t interested in hiring them. The year before the War of the Spanish Succession concluded, for instance, the British Navy employed nearly 50,000 sailors. Just two years later it employed fewer than 13,500 men. Most sailors’ only other legitimate maritime option was the merchant marine. This was fine for those who no longer had a taste for sea banditry and didn’t mind taking a pay cut. But it posed a problem for those who did. Between 1689 and 1740 the average able seaman’s monthly wage varied from 25 to 55 shillings; that’s £15 to £33 a year, or about $4,000 to $8,800 in current U.S. dollars. The high end of this range was during war years when privateers and the navy bid sailor wages up. The low end was during peace years when hordes of ex-privateer and navy seamen flooded the labor market searching for jobs. A privateer, or even a merchant seaman, who had become accustomed to higher wages during war couldn’t have been pleased about his pay falling by half when war en...