![]()

Job in the Ancient Interpreters

CHAPTER 1

As modern readers informed by Enlightenment presuppositions and decades of historical critical scholarship, we think we know what the book of Job is and how to approach it. Like any other book, we assume it must be a fixed text with a beginning, middle, and end. We take for granted that it was written at a particular time by a particular person. We might (or might not) also ask for what purpose it was written. Knowing this is enough for us to know what the book is about, and to judge later interpretations and adaptations. We praise as legitimate those that illuminate things we too see in the text. We are skeptical of those that make claims that seem only weakly borne out by the text in question. And we dismiss, perhaps with disdain, those interpretations that interpret it in terms of things outside of it, especially if, as it seems to us, they at the same time ignore the plain meaning of the text.

All of these considerations impede our ability to assess early biblical interpreters. It looks to us as if they aren’t reading the same text at all. So consistently do they miss what we think is the plain meaning that we suspect they’re not even trying to read it faithfully. Indeed, they may seem to us willfully to ignore and obscure the meaning. In the case of the book of Job, the traditional “patient Job” reading seems to us to be painted over the actual story of Job, which is, at the very least, much more complicated.

The extent of early readers’ ignoring or obscuring is much exaggerated, however. The result may appear obfuscatory, but they were trying to do something quite different from this. To appreciate what they were up to, we need to pluralize our sense of ways of reading—and of books. In this chapter we’ll develop these new senses by looking at the book of Job as one of multiple renditions of a story, and as one of multiple texts in scripture. We’ll explore the former through the Testament of Job, the most substantial residue of the popular and largely oral tradition sometimes known as the legend of Job. For the latter we’ll look at the Talmud’s midrashim on Job, and at Gregory the Great’s moral and allegorical reading of Job. Each of these is doing something fundamentally different, and we need to dwell on those differences. But as a group they exemplify a distinctive way of approaching texts unfamiliar to us today which may yet have something to teach us. To help us shed the expectation that the book of Job is a clearly defined and self-interpreting piece of text, we start with a quick survey of the forms and settings in which it has been encountered over the centuries.

Books of Job

Whatever your image of the book of Job, it is probably a poor guide to understanding its history. We live in the only period in its history when it is widely available in translations without commentary and marketed on its own as a freestanding book. The materiality of independent binding might lead us to suppose the book of Job was always understood to be at least implicitly self-sufficient, but the story is quite different. The forms in which people encountered it emphasized that it was part of the library of scripture (biblia comes from the Greek word for books, plural) and, until very recently, was thought impossible to read unassisted.1

The Bible was never read in a linear way, one book following another, but the organization of its books remained significant and a subject of much discussion. In the Hebrew Bible, the Tanakh, the book of Job forms part of the third section, Ketubim (Writings); it often—but not always—came after Psalms and Proverbs and before the five Megillot or “little scrolls,” the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther. It offers God’s longest speech in scripture, and, in the chronology of the Tanakh, his last. If one read the Tanakh as if it were a biography of God, one might conclude that after the encounter with Job “God subsides,” and that divine silence begins within, not after, the time of the Bible.2

The Christian Old Testament shares most books with the Tanakh but not their order. In the Tanakh the Ketubim is the last of three divisions, coming after Torah and Prophets. In Christian Bibles the Writings come between the Pentateuch and the Prophets. Read a Christian Old Testament from start to finish and you will not find God subsiding with Job. Through his prophets he has a lot more to say, all of it interpreted by Christian readers as setting the stage for the Christ. Many interpreters thought Job was a kind of prophet, too:

For I know that my Redeemer [go’el] lives,

and that at the last he will stand upon the

earth;

and after my skin has been thus destroyed,

then in my flesh I shall see God,

whom I shall see on my side,

and my eyes shall behold, and not another.

(19:25-27a)

Job was also a “type” of Christ. “Job dolens interpretatur, typum Christi ferebat,” Jerome wrote: Job’s very name means sorrowing or suffering, and he was a prefiguration of Christ.3 As we will see with Gregory the Great’s Morals in Job, the man from Uz’s every word and gesture were understood to anticipate the life and message of Christ.

While the Bible was regarded as the book par excellence, the library of scripture wasn’t a text like others. For one thing, it didn’t look like other texts. The care taken in the writing, reading, and preservation of Torah scrolls is well known. Elaborately bound and beautifully scripted Christian codices presented the Bible monumentally as well—and not just because it was a great deal of text to present between two covers.

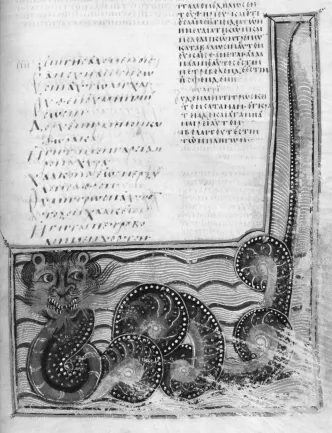

Many manuscript Bibles were illustrated. The book of Job offered artists many novel opportunities for visualization. The events of the destruction of Job’s life and livelihood were dramatic spectacles, but the figurative language of the speeches that make up the bulk of the text offered opportunities of its own. The book of Job is distinguished among biblical texts by the richness of the natural imagery employed in its speeches, many of which were also understood allegorically. Byzantine illuminated Bibles show long-standing traditions and subtraditions in the representation of these figures and figurations.4 These visual representations were important to the experience of the text even for those who could read. Much of the drama of Job concerns the limits of language and the power of representations that go beyond them.

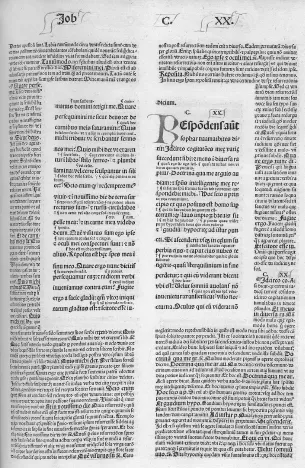

For most of its history, encountering the biblical text on its own was as good as impossible. Scripture differed from merely human literary productions through a depth of meaning which demanded elaborate apparatuses of theological commentary. The clarifications of inspired and authorized interpreters were indispensable and the production of texts reflected this. Manuscripts and early printed editions of the Bible were often encased in so many layers of commentary that the words of the biblical text themselves seem mere islands in a sea of smaller, handwritten commentary. The twelfth century saw the emergence of a standardized synthesis of the commentaries that had been welling up around the margins and even between the lines of Christian Bibles, the Glossa Ordinaria. Approaching the text without reference to (or at least awareness of) the authoritative commentaries of church fathers and others was literally impossible. Commentary wasn’t trying to bar access to the text, but to facilitate it (see figure 3).

Figure 2. The wealth of figurative language in the speeches in the book of Job provided opportunities for great artistic virtuosity. In this ninth-century Byzantine Bible known as Vaticanus Graecus we see Leviathan, the great sea monster, alongside the Septuagint text of 41:17–20. Image Vat.gr.749. -p.238r. Reproduced by permission of Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved. © 2013 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

How would a Christian reader in the Middle Ages have encountered Job? Jerome’s pronouncement that Job means suffering and that he was a type of Christ was the entry point:

Typically, approaching the beginning of Job, one is first greeted by a double prologue contributed by Jerome, one part bearing on the Septuagint and the other on the Hebrew text. This is followed by an expositio of the second part of the prologue and a double praefatio by Nicholas de Lyra, to which is appended an anonymous additio. Thereupon comes a somewhat lengthy “Prothemata in Job” based on Gregory’s Moralia. Only now have we finally arrived at the first verse of the book of Job.5

Even then, it was slow going. Commentary illuminating the significance of the words “There was a man in the land of Uz by the name of Job” (1:1) took up several pages, as every word was parsed and reparsed. Our discussion of Gregory’s Morals in Job will give a taste of the kind of significations offered.

Most people didn’t have access to the Bible, and wouldn’t have been able to read it if they had. The Bible was accessible to many more in visual form, and even in Bibles, images were more than mere illustrations. Works like the twelfth-century Bibles Moralisées and the cycles of stained glass windows they informed paired images of Old Testament and New Testament scenes, showing the way every Christian was to understand the Old Testament. Arguably these images illustrate the play of type and antitype that defined the way medieval Christians viewed the Bible more directly than textual commentaries can. The claims being made were not about words. Through typological anticipation God wrote in events and scenes. To see the same structure, the same postures of different bodies, in scenes paired in this way is to understand how divine purpose wove through events. It was not necessary for the faithful to be able to read written language to understand the way God wrote history.

Figure 3. In the medieval Glossa Ordinaria—here a sixteenth-century printed version—the biblical text floated like an island in a sea of authorized interpretation. Here we see the end of Chapter 19 and the beginning of 20. Courtesy Firestone Library, Princeton University.

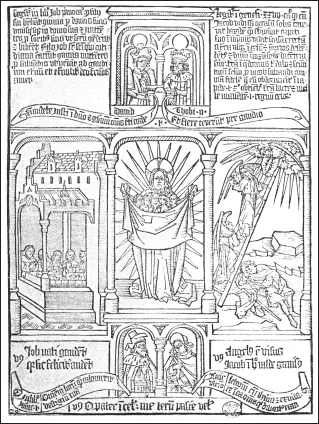

The larger structure of history and saving knowledge was made clear in a different way in the fifteenth-century works known as Bibles of the poor, Biblia Pauperum. Here scenes from the life of Christ (mainly his miracles and passion) are presented in sequence, each in an elaborate architectural frame. Appearing on either side, like buttresses holding up a gothic church nave, are typologically related Old Testament scenes. Supporting text scrolls from pairs of prophets unfurl above and below, so the New Testament scene is framed by six allegorical, typological, or prophetic anticipations. The only significant blocks of text decode the two Old Testament scenes depicted.

Figure 4. The Biblia pauperum (Bible of the poor) represented the relationship of Old to New Testament architecturally. Old Testament scenes were taken out of the context of their own stories to support New Testament interpretation. Job’s children are feasting at left. Courtesy Firestone Library, Princeton University.

The correlations are anything but straightforward. On one page, celebrating the feast awaiting the resurrected, we see Job’s children feasting as a support to an image of Christ gathering the blessed in his mantel (see figure 4). The accompanying text explains:

We read in the Book of Job, chapter 1[:5], that Job’s sons after sending for their sisters so they could eat and drink with them held a feast in each of their homes. The sons of Job are the holy ones who held feasts daily, sending for those who were to be saved so they could come to eternal joy and enjoy God forever, amen.6

That Job’s children are killed in the middle of one of their daily feasts just a few verses later (1:19) is beside the point; this is an image of heaven. Refracted in the light of the gospel, however, this may be irrelevant. What was important may simply have been that Job’s sons numbered seven and their sisters three (significant numbers both), and that they held feasts daily. But we shouldn’t suppose readers weren’t familiar with the story of Job, which could add further shadings of meaning. Job 1:5 also tells us that Job “offer[ed] burnt-offerings” for his children, thinking “ ‘It may be that my children have sinned, and cursed God in their hearts’.” Perhaps “Everyman”-like reflection was called for? The central panel, referring to the story of Dives and Lazarus (Luke 16:22), doesn’t portend well for feasters, either.

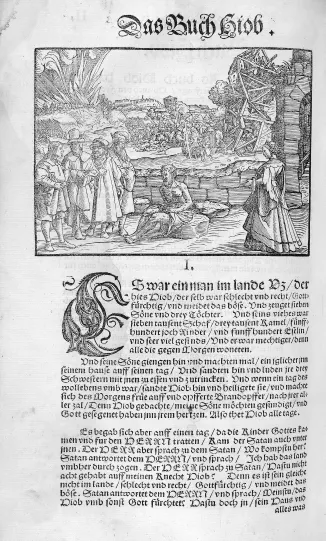

Despite the idea of sola scriptura, the printed Bibles of the Reformers didn’t immediately dispense with glosses, or with illustrations. Editions of Martin Luther’s German Bible soon included an already stock image conflating a number of scenes from Job (see figure 5). Messengers bring news of the calamities we see in the background behind them—fire from heaven, camel abduction, and the collapsed house of Job’s sons—to a Job who is already afflicted with sores and attended by friends—friends whose gazes mirror the flames above them. (The youngest, Elihu, seems to be speaking.) Job’s wife remonstrates from the side, her profile continuous with the destruction above her. In later iterations of this image, storm clouds are brewing overhead; in some, Job is illuminated by a beam of light coming from an opening in the clouds, making every part of the story simultaneous.

It is not only for reasons of economy that such illustrations present all that happens in Job’s story at once. The Bible doesn’t merely narrate a history—a series of events whose meaning lies only in their place in the sequence. Each element is significant on its own and potentially relevant at any time. Different parts may be relevant simultaneously. A composite image, which the eye can take in at a single glance or navigate in endlessly different ways, gives us a better picture of how a familiar narrative like Job’s was experienced. In this world, prosperity is always haunted by calamity, just as tragedy is attended by hope. Even if Job passed through the storm only once, for the faithful encountering his story over and over—as text, and in their own lives—he may seem to be spinning in it still, just as we are.

Figure 5. Martin Luther’s German Bible was not the first vernacular translation of the Christian Bible, but it marked a sea change in public access to scripture. The engraving that accompanied the translation of the book of Job in this first complete edition of Old and New Testaments (1536) brings together many parts of the story in one image. Courtesy Fire-stone Library, Princeton University.

The allegorical realms of the Glossa have lost their sway, but Bibles full of clarification and commentary continue to shape the way we understand the book of Job. Even among literalist Protestants who allow no extra-biblical sources for interpretation, the Bible has been mined to reveal a dense network of internal references and clarifications (see figure 10). Texts like the Jewish Study Bible balance the best modern translation with interpretive suggestions based on philological work of medieval and modern provenance, suggesting that passages might (or might not) benefit from reordering (see figure 9). And the book of Job continues to reach new readerships, as Christian missionary translation programs reach out to hundreds of languages, and engage new worlds of signification (see figure 11).

Filling Gaps

The book of Job as we know it today seems to speak out of both sides of its mouth. Job helps God...