![]()

PART I

Contemporary Cultural Contexts

![]()

Chopin’s Oneiric Soundscapes and the Role of Dreams in Romantic Culture

HALINA GOLDBERG

[A composer’s] logic … is the dreamlike logic that combines the most daring and contradictory visions, and yokes them together. To understand it, one must be dreaming oneself.

—Józef Sikorski

The notion of dreaming in music immediately brings to mind Chopin’s nocturnes.1 Indeed, this genre’s explicit association with the night invokes the oneiric realm, the domain of dreams. Yet, as we investigate listeners’ responses to Chopin’s music more closely, we discover that they repeatedly refer to dreamlike episodes in his compositions in other genres, and that in addition to timbral representations of nocturnal haziness Chopin employs other compositional techniques that bring about the experience of dreaming.

Modern-day scholars’ responses to the perceived dreamscapes in Chopin’s compositions follow on the heels of a long tradition of hearing his music as a dream, a tradition that originated with his friends and contemporaries.2 While other modern scholars, for example James Parakilas in this volume, highlight the compositional and stylistic language of Chopin’s dream world and seek to interpret the experience of hearing it, my task in this essay is to explore the cultural milieu that shaped the composer’s penchant for oneiric soundscapes and his contemporaries’ responses to it. What were the cultural reasons for the increased interest in oneiric visions? Under what circumstances would Chopin have been exposed to these cultural trends? What was music’s role in portraying oneiric experiences? What qualities of Chopin’s music evoked dream images for his audiences? What significance might dreams and dreaming have held for Chopin and his audiences?

Chopin’s Peers on His Musical Dreamscapes

Chopin’s contemporaries frequently commented on the dream soundscapes they heard in his music. Needless to say, the nocturnes most often elicited such responses. Indeed, in the first extensive Polish assessment of Chopin’s music, published in Poznań in 1836 by Antoni Woykowski, we read that Chopin’s nocturnes, in contrast to John Field’s works that are “dry and dull,” are “true dreams of a tender, pure soul, violently moved by the emotions of a silent night.”3 Around the same time Gottfried Wilhelm Fink, in his review of Chopin’s Nocturnes, Op. 27, described their character as that of “The Dream, who revels in round dances with Longing [Sehnsucht].”4 Fink’s evocative image relates Chopin’s dreamy soundscape to Sehnsucht, that quintessentially Romantic concept of longing for the Unattainable, the Infinite, the Ideal. At face value Woykowski’s comment appears to highlight the intense emotionalism of Chopin’s nocturnes, placing them in a sphere of Sentimentalism, but in full context it becomes clear that Woykowski also understands these pieces as offering an insight into the ideal realm, for in the same essay he describes Chopin’s music as “a magical art that gives man a glimpse of his higher origins and lifts him instantly from this vale of tears to the happier lands above.”5

Reviewers also invoked oneiric imagery in relation to Chopin’s other works. An 1842 article in Revue et gazette musicale de Paris offered a general observation that Chopin’s compositions are “a dreamy pleasure which shuns noisy outbursts and penetrates the soul with vague melancholy.”6 More specifically, in 1837, in his review of the A-flat Major Etude from Opus 25 performed by Chopin, Robert Schumann remarked that “when the étude was ended, we felt as though we had seen a radiant picture in a dream which, half-awake, we ached to recover.”7 Aleksander Jełowicki, who befriended Chopin in Paris, heard his friend’s improvisations as dreamy memories of Poland. He recalled that when they were together, missing home and remembering old times, Chopin would sit at the piano and his music made Jełowicki “dream of home, and wake up dreaming.”8

In their descriptions, the listeners to Chopin’s music place themselves in diverse relationships to the dream: in some instances, exemplified by Jełowicki’s account, they are dreaming while listening to the music; in others, represented by Schumann’s description “half-awake,” they remember the dream; others still, for example Woykowski, witness a memory of someone else’s (the composer’s?) dream narrated by the music. For Jełowicki, an ardent Polish patriot and a veteran of the November Uprising of 1830, dreaming and memory are intertwined with nostalgia for Poland, a mode of listening that I have described elsewhere.9 This interplay between dream, night, memory, yearning, and nostalgia appears time and again in descriptions of Chopin’s music, perhaps most beautifully captured by Fink, who with his characteristic eloquence, observes that Chopin’s “forms are always bathed in a twilight, from whose hazy fragrance shadows of memory now softly arise and play with longing, now rage by in a tempest, terrifying and eerie.”10

Figure 1. Teofil Kwiatkowski, Chopin’s Polonaise—Ball at the Hôtel Lambert, (formerly Polonez—Rêve de Frédéric Chopin Pianiste), watercolor, 1857. Muzeum Narodowe, Poznań.

Such dreaming and remembering, tinged with nostalgia, are the topic of one of the most famous paintings representing Chopin, by Teofil Kwiatkowski. The title usually given to this work is Chopin’s Polonaise—Ball at the Hôtel Lambert, but before it became known under this name, the painter showed this watercolor in 1859 at the Salon under the title Polonez—Rêve de Frédéric Chopin Pianiste. The work dates from around 1857, and thus was painted by a close friend of the composer just a few years after his death. The image is composed of three groups of figures: on the left are easily identifiable members of the Czartoryski family, who serve as hosts of the event (hence the reference in the better-known title of this painting to the Hôtel Lambert, Prince Adam Czartoryski’s Parisian residence and a synecdoche for the political faction associated with him); on the right, a group of artists and intimates surround Chopin at the piano, among them the poet Adam Mickiewicz, Chopin’s student Princess Marcelina Czartoryska, George Sand, and Kwiatkowski himself; in the center allegorical and historical figures (including the celebrated fifteenth-century knight Zawisza Czarny) are dancing a polonaise.11

In Kwiatkowski’s painting, apparitions and allegorical figures conjured up by Chopin’s music mingle with real persons, contemporary and historical: an allegorical peasant girl, invoking the “pure” Polish folk, stands by the piano; to the right of the composer two angels listen closely to the music; among Chopin’s intimates gathered behind the composer, a figure of guerrier gaulois, representing the primeval spirit of France, looks on from the shadows. The winged figures appearing throughout the room are historical rather than allegorical: they are the Winged Hussars, members of the elite Polish cavalry associated with King Sobieski’s victory over the Ottomans at Vienna. Temporal and spatial frames are likewise conflated: the informally dressed Chopin, at an upright piano, exists in the same time and space as the illustrious and formally clothed hosts. Standing to his right, Mickiewicz, by the late-1830s already famed for his description of the polonaise in his epic Pan Tadeusz (reproduced in the introduction to this volume), seems to beckon the ladies to dance. The Polish bard is aptly dressed in kontusz and ˙zupan, the archaic traditional attire of the Polish nobility, which was strongly associated with the polonaise and belonged to the nostalgically recalled era of sovereign eighteenth-century Poland (a cultural trope that is addressed in Eric McKee’s essay in this volume).12 Not only does historical time coincide with contemporaneity, but even the modern figures in the painting reference a variety of time frames: Chopin and Mickiewicz, who at the time the painting was completed were already dead, are placed in the same time frame as new members of the Czartoryski family, such as Princess Maria Amparo, who only in 1855 married Prince Władysław. The pose of Kwiatkowski is a visual quotation from his well-known painting representing Chopin’s last moments in 1849.13 Likewise, the image of Chopin is reproduced nearly verbatim from an intimate, impromptu watercolor Kwiatkowski made in 1847 (see Figure 3). The actual Hôtel Lambert was a luxurious and bright residence dating from the period of Louis XIV, and designed by an architect and artists closely associated with the king. The space depicted by Kwiatkowski, however, is defined by murky Romanesque arches supported by columns crowned with medieval capitals, which imbue it with an air of mystery and timelessness.14

Figure 2. Detail of Chopin at the piano surrounded by friends and allegorical figures, Chopin’s Polonaise—Ball at the Hôtel Lambert.

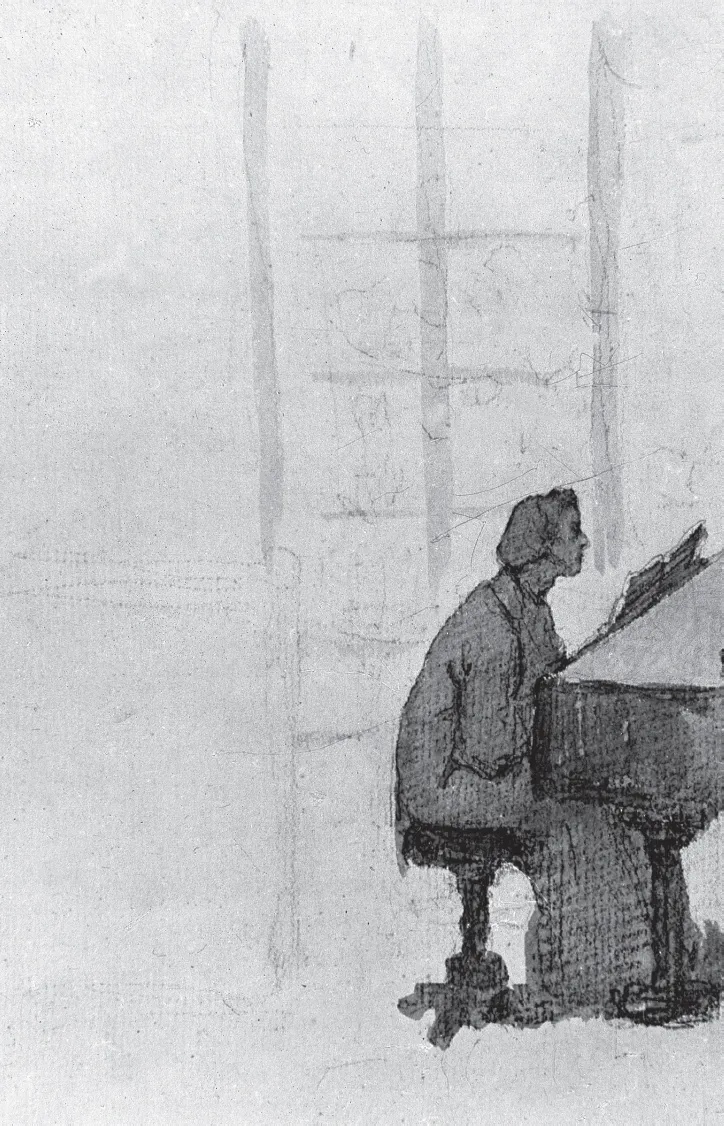

Figure 3. Teofil Kwiatkowski, Chopin at the Piano, watercolor, 1847. Muzeum Chopina, Warsaw.

This disjointed, conflated sense of time and space is characteristic of dreams and memories. But Kwiatkowski leaves much to the viewer’s imagination. He makes us ask: Who is the dreamer? Is it Chopin dreaming about (remembering?) Polish history while improvising? Are his listeners dreaming (remembering?) in response to his music? Is it Kwiatkowski dreaming about (remembering?) Chopin’s dreams of Poland’s past? Or is it all taking place concurrently—memories and dreams being endlessly reflected in mirrors of time?

Chopin’s “Dreamlike Logic”: Musical Vocabularies of Memory, Nostalgia, and Dream

In Chopin’s music, as in Kwiatkowski’s painting, the states of dreaming and remembering overlap and share similar musical vocabularies, and nostalgia for his homeland meets Romantic longing. In recent decades scholars of memory have ascertained that our memories distort the recalled experience through the fading, blurring, and fragmenting caused by a weakening of neuron connections in our brains.15 These scholars often turn to Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu as the paradigmatic artistic representation of memory.16 Long before Proust, however, the composers of the early nineteenth century—especially Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, and Chopin—mastered the art of capturing in their music the distorted experience of a recalled past. In Chopin’s compositions, we hear techniques beyond the fragmentary recall of a theme or a motive: he renders us subject to temporal distancing through auditory distortions—fading, blurring, and fragmentation. These distortions, especially in combination with the national connotations of the mazurka genre, invoke nostalgia in its original sense: as a spatial and temporal displacement from one’s homeland.17 Thus when Jełowicki speaks of Chopin’s improvisations as dreams of Poland, he references this patriotic mode of nostalgic remembering and dreaming. But for the Romantics nostalgia also carried an association with a broader concept, Sehnsucht, an existential yearning, a longing for the Unattainable. In genres that did not specifically reference Poland, such as the etudes or nocturnes, Chopin’s contemporaries heard musical dreams and memories that reflected these broader Romantic ideas. Therefore, when Fink references memory and dreaming in relation to Chopin’s Nocturnes, Op. 27, and Schumann refers to these concepts in relation to Chopin’s first etude from Opus 25, they do so not in the patriotic sense, but within this broader Romantic framework.

Both mental states—dreaming and remembering—are characterized by fragmented thoughts and images, which throughout Chopin’s works are suggested by thematic and motivic fragmentation. On a subtler pianistic level, both can likewise be evoked by the fading and blurring of sound that Chopin achieves through soft dynamics, the use of pedal points, drones, or non-chordal tones, rubato, and his masterful shading of pianistic sonorities, including, of course, his exquisite use of the pedals, both damper and una corda pedal.18 In the coda of the B-flat Minor Mazurka, Op. 24, No. 4, for example,

the tempo slows down and the volume fades out at the end, leaving only a faraway reverberating specter of a mazurka. He indicates a performance that imitates the experience of receding sound through copious expressive comments—ritenuto, diminuendo, calando, mancando, sempre rallentando, and smorzando—that accompany repeated pianissimo markings. A blurring that heightens the sense of distancing is further achieved through harmonic means and a lingering pedal (note, especially, the last four measures). The melody, which alludes to an inner voice motif from the opening, echoes with repetitions, closing as an eerie, Phrygian fragment.19

While there is an overlap in compositional strategies that invoke dreams and memory, some of the techniques point more directly to the experience of dreaming than remembering. In music that uses topics associated with the nocturnal, such as the nocturne, berceuse, or barcarolle—not just in pieces in these genres but also in others that reference them as topics, for example within the ballades and scherzos—p...