![]()

| I | Empirical and Theoretical Motivations |

![]()

| 1 | The Political Economy of Cultural Wealth |

Miguel A. Centeno

Nina Bandelj

Frederick F. Wherry

Men of all the quarters of the globe, who have perished over the Ages, you have not lived solely to manure the earth with your ashes, so that at the end of time your posterity should be made happy by European culture. The very thought of a superior European culture is a blatant insult on the majesty of Nature.

—J. G. Herder

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CULTURE AND THE ECONOMY—including its effects on economic development—has a long academic history and has been the subject of considerable study and debate in the past few years. We are still asking which shapes which. Is it, to use Marx’s words, “the consciousness of men [sic] that determines their being” or, on the contrary, “their social being [involved in relations of production] that determines their consciousness” (Marx [1859] 1978: 4)? Does cultural wealth make economic capital accumulation more likely, or does economic accumulation provide the means for making the wealthy appear more attractive than the working classes?

We can conventionally date the start of such discussions to Weber’s thesis in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Weber [1905] 2002). Weber downplays the relations of production and the conflict between the propertied and the propertyless classes when he explains the rise of modern capitalism. Instead, Weber emphasizes the Calvinist ethic and worldview that led people to become dedicated to work and to engage in trade and investment. Although he is not the first to do so, Weber is credited with linking how people think about the world to how they act on its economies. Later analyses of the same ilk include the work of modernization theorists in the 1950s and 1960s (Apter 1967; Bellah 1958; Levy 1962) and arguments about how a civilization’s culture accounts, or not, for its industriousness and potentially leads to the conflicts between nations (Huntington 1996). For instance, David Landes has argued that the “rise of the West” was intimately linked to the particular cultural characteristics (attitudes toward science, thrift, and industriousness) of the societies of Western Europe. It is these cultural advantages, proposes Landes, along with a hospitable climate and a more competitive political system, that explain why there is more economic wealth in the West and more poverty elsewhere (Landes 1998). Alejandro Portes and Patricia Landolt (2000) have critiqued this line of thinking for its circular reasoning: Industrious nations are hypothesized to do industrious things. Avoiding the truism requires a close engagement with how we define culture, what its material and ideational sources are, and how culture as a predictor is not merely a restatement of the cultural, social, and economic outcomes it is presumed to cause.

Immanuel Wallerstein (1990) launches a critique against cultural universalism from the political economy perspective. Wallerstein posits that the world system has existed for centuries and that the struggles for control over scarce resources have shaped the present-day advantages and disadvantages that countries experience in the global economy. For Wallerstein, culture is camouflage: The tactic of “creating a concept of culture as the justification of the inequities of the system, as the attempt to keep them unchanging in a world which is ceaselessly threatened by change . . . therefore the very construction of culture becomes a battleground” (1990: 39). Universalist claims of cultural values and absolutes hide particularistic facts, and this occurs both globally and locally (where the particular “us” is turned into a universalistic “us” to disguise inequality). Because there is a hierarchy of states and a hierarchy within states, the ideology of universalism serves as a palliative and a deception. Wallerstein notes how such cultural arguments can be used to justify both outcomes that may result more from historical legacies as well as those resulting from current-day attitudes toward work, investment, and savings. The discourse on culture functions to “blame the victim” by assigning to the global losers a culturally generated “original sin.” Thus, the development discourse wraps the world in universalistic legitimacy and then ascribes a particular position to failure in meeting universalistic criteria.

Like Wallerstein, Pierre Bourdieu (1984, 1993a) is cognizant of the power hierarchies but provides an understanding of the links between the economic and cultural at the individual level and sheds light on how understandings of what is “universally” valuable set in. Bourdieu argues that the tastes people have for different types of cultural performances and products depend on the material and social conditions of their existence. The possession of economic capital (money, assets), but mostly cultural capital (educational background and ease with and knowledge of the higher arts), enables an individual to understand what will be generally regarded as high versus low culture, what will be worthy of widespread recognition, and what will deem disdain. But aesthetic tastes do not hover above humankind, in the intellectual stratosphere where only the chosen may travel; rather these tastes are grown during periods of struggle, and these struggles over taste happen among groups of people with accumulations of economic and cultural capital. As understandings about what is “universally” valuable set in, the struggles that made these understandings congeal are effaced.

While acknowledging the agency of the dominant in writing the rules for what is universally valuable and therefore worthy of deference from the dominated, Bourdieu also situates these struggles and the dispositions of the dominant and the dominated in fields where the varying accumulations of cultural and economic capital (along with other forms of capital) shape the dispositions that actors have for revering or politely rejecting an aesthetic form such as design styles, artworks, and musical expressions. The actors themselves are unaware that their dispositions are shaped by the objective conditions of their existence and that the accumulations of different forms and quantities of capital makes them more disposed toward some forms of culture but not others.

Not only are individuals unaware of where their tastes come from, but they are also in denial about how their tastes for particular cultural forms or their respect for a specific aesthetic might lead to economic profits. Bourdieu argues that, for individuals to profit financially from culture, they often disavow their economic motivations, even to themselves, to keep on course their performance of the desire for and protection of culture in its “authentic” form. Culture cloaks power as both the dominant and the dominated deny that their concerns for culture have economic (or even political) implications, thereby rendering the existing hierarchies of inequality more stable by making them seem to be a reflection of the natural order of things. Who should go against nature and expect to win? It is by virtue of sincere belief and taken-for-granted denials that culture may do its work.

In justifying hierarchies of inequality, Saul Bellow cavalierly remarked: “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans? I’d be glad to read him.”1 Bellow implied a global division of talent akin to social Darwinism’s survival of the fittest. The most common reaction to such a claim may be best referred to as cultural relativism. Such a perspective denies the possibility of an absolute scale of cultural value. There is no “best” novel (nor is the novel necessarily the “highest” literary form). Cultures and cultural products need to be understood in their social and historical contexts. From this perspective, Jane Austen is not necessarily one of the leading depicters of the condition of female subjugation and emancipation, but a chronicler of the manners and concerns of Regency Britain. These novels are no more entitled to belong to a universal canon than the oral epic tales of Shaka Zulu’s conquests.2

Interestingly, the two positions, universalism and relativism, can use the same references to argue their point. Arguing for their universal value, one side can point to the apparent global reach of Shakespeare, Mozart, and Michelangelo to defend the supremacy of a particular cultural tradition. The other perspective can similarly point to these artists and emphasize that it is no accident that they are so highly regarded because they are all representatives of the Western culture that militarily conquered and dominated the world. Had tribes from the southwest Pacific Ocean conquered and dominated the world, the argument goes, the Proust of the Papuans, in the words of Saul Bellow, would have gained more global prominence and regard than Proust (of the French) and those similarly deemed estimable.

This debate about the universality or relativity of culture is important for the discussions of the cultural wealth of nations. How should one judge the relative cultural wealth of parts of the world and its origins? Can we speak of a cultural wealth begetting economic development, or is it more accurate to say that the worth of culture is, at least partly, determined by the amount of money and gunboats behind it?

A critical first step in resolving this debate without falling into an ideological abyss is to make the phenomena as concrete as possible. For the purposes of this chapter, let’s define cultural wealth as the value added derived from the intangible qualities of products and services emanating in part from the perceived cultural heritage of the people engaged in their production. To what extent is the market value of a cultural item simply a reflection of the political and economic position of the place from which it originates? Conversely, can local cultural products from less powerful nations achieve some success in the global cultural market and then reflect some of this glory on their national origins, thereby making it arguably easier for the next cultural export from their country? Similarly, global disdain for particular cultures can make it extremely difficult for its products in the marketplace even if their designs and production techniques closely resemble those of products from elsewhere that command higher prices and that enjoy widespread recognition as valuable (Wherry 2007). This leads us to ask about the historical conditions in which products find themselves esteemed and why this esteem is conferred in some time periods but not others (although the products have existed across time).

It is vital to understand that such a series of questions goes beyond the simple issue of “Americanization” or commoditization of global culture, as the advocates of cultural imperialism propose. Nor is this an argument for hybridity (Pieterse 1994) and the “localization” of the global (Ritzer 2003). What we need to understand is the relationship between the “value” of culture or cultural artifacts and a position in a global “world-system” (loosely understood). In short, what is the relationship between global political economy and global cultural wealth? While our ambition is not to provide a definite answer to this question, we want to motivate such an inquiry for future research by posing parallel questions, such as: Is there a global class system? Is there a global “cultural” class system? How does it manifest itself? We take up these questions by scrutinizing, first, the hierarchies in global cultural production and, second, in global tourism.

The Culture of Global Class

Is there a global class system? By class system we mean three things. First, does the distribution of global wealth demonstrate dramatic gulfs between regions, and does this level of inequality merit the label of a “class system,” whatever the mechanisms of its creation and maintenance? Second, does a nation-state’s position within the global hierarchy of cultural wealth enable or disable potential sources of income? That is, does the nation-state’s position in the global pyramid determine access to cultural production capacities? Third, does one’s position in the global hierarchy help define expected cultural consumption patterns?

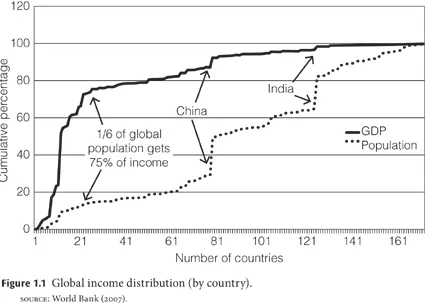

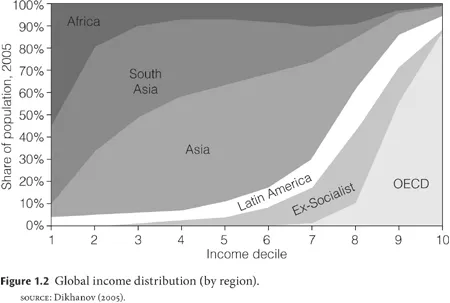

As to the first, there is little doubt that the world is divided between regional haves and have-nots. Ignoring for the moment internal distributions of income, the group of richest nations representing roughly one-sixth of the world’s population currently produce and consume three-fourths of global production (Figure 1.1). At the very top we have the twenty-five wealthiest economies, which consist almost exclusively of countries in northwest Europe and its predominantly white colonial offshoots in North America and Oceania. The global wealth hierarchy is even more skewed. One estimate is that North America accounts for 34 percent of the world’s wealth, Europe 30 percent, the Asia-Pacific region 24 percent, and the rest of the world 12 percent. The top five countries (the United States, Japan, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom) account for two-thirds of the world’s wealthiest individuals (Davies et al. 2006). Even more striking than differences between nation-states is the (estimated) ethnic and racial distribution of global plenty as shown in Figure 1.2. The global poorest consist overwhelmingly of Africans and South Asians, while the vast majority of the global rich are of European descent (Dikhanov 2005).

Similar distinctions among the different parts of the world may be observed in less precise measures such as the implicit value of an individual human life. Note that the accidental death of a group of European descendants somewhere in the globe will merit much more global media attention than the equivalent number of Africans or Asians. For example, Google counts comparing coverage of the lost Air France jet in route to Paris and a Yemenia flight that crashed in Comoros within days of each other indicate that immediately after the crash the Air France flight disaster received at least four times the news coverage of the Yemenia one. News from places such as Bangladesh or the Philippines appears to be merited only if more than a hundred people die in particularly tragic circumstances. It seems unimaginable that the news media would pay scant attention to 2 million violent deaths occurring over a decade in Europe or North America, yet the news hardly considered this magnitude of violent death remarkable for the eastern Congo. Similar distinctions would appear to apply to the application of human rights in different parts of the world. Take, for example, this fictional interchange from Our Man in Havana between the protagonist Wormold and the Batista-era police captain:

It would appear that the world remains divided, in the words of Graham Greene’s Captain Segura, between “the torturable” and “the nontorturable.” In other words, people from different parts of the world obtain different types of status, according some with more rights but others with more obligations, making some of them more remarkable, more easily seen, and more worthy of emulation. These differences in status have material and bodily consequences.

The major question is whether this inequity is autoreplicating and durable (Tilly 1999). Does position in the global order shape the economic opportunities of these societies? The notion of the “new international division of labor,” a result of the global industrial shift whereby, in search of low cost, manufacturing is relocated from the developed Western countries to developing countries in Asia and Latin America, is explicitly predicated on some workers receiving significantly less pay than others and receiving less governmental environmental and safety protection (Centeno and Cohen 2010; Frobel, Heinrichs, and Kreye 1980; Gereffi and Korzeniewicz 1994). The global South–North migration is another manifestation of such distinctions: Citizenship in a privileged northern country can practically assure that many of life’s disagreeable tasks will be done by those with less coveted national identities, emigrating from the South; therefore, one could argue that there is a substantial premium for already being wealthy, leading the hierarchy of cultural production to resemble the global economic hierarchy.

Possessing economic wealth makes generating cultural wealth more likely, and cultural wealth itself acts as a resource from attracting and generating economic wealth; yet the creation of cultural wealth is not a straightforward process. Studies of cultural imperialism suggest that the dominant class consciously and deliberately marshals its ideological and cultural resources (including its instruments of physical and symbolic violence) to maintain its dominant positions within its own nation-states and across entire regions of the world; however, some forms of symbolic domination result from institutionalized practices and/or historical accident. Paying attention to these practices, historic...