![]()

1

Creating and Debating Judicial Independence and Accountability

Currently the conflict in the states over judicial independence and accountability focuses on judicial selection and tenure. Historically, however, the debate in the states has been far broader, a continuing constitutional conversation about the role of courts and judges in a republican polity. This conversation has involved the character of the judicial function and the place of legal professionals and laypeople in the administration of justice. It has also addressed from whom judges must be independent and for what purposes, to whom they should be accountable, and how that might be accomplished without jeopardizing independence. The states have tried various answers to these questions, and even states that resolved these issues at one point in time later revisited them. Simply put, the history of judicial independence and accountability in the states has been not a steady progression toward a single ideal but rather a record of competing and diverse conceptions of independence and accountability, with the prevailing understandings changing over time and among the states. This chapter traces the conflict over the contested concepts of judicial independence and judicial accountability from the founding era to the mid-nineteenth century. Chapter 2 extends the analysis into the twentieth century with particular emphasis on judicial selection and judicial tenure, and Chapter 3 analyzes the current debate. Political practice and political debate in the states highlight the complexities of judicial independence and judicial accountability and, in so doing, provide the basis for understanding and assessing current claims and arguments.1

Independent of Whom?

Constitutional Arrangements

Before the American Revolution, colonial governors, selected by the Crown, appointed judges, raising concerns that those selected might be biased in favor of royal interests.2 Those receiving these patronage appointments served at the pleasure of the Crown rather than, like their counterparts in Britain, during good behavior, increasing fears that they might “pronounce that for law, which was most agreeable to the prince or his officers.”3 Thus, the issue of judicial independence first arose in America in reaction to excessive executive control over—and possible manipulation of—the administration of justice.4 Thus the Declaration of Independence charges the king with “refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers,” with making “judges dependent on his will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries,” with “depriving us in many cases of the benefits of trial by jury,” and with “transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offenses.”

The Declaration’s indictment of the Crown, it should be noted, is framed not in terms of judicial independence but in terms of popular access to justice, understood as encompassing both the availability of judicial forums (“refusing his assent to laws establishing judiciary powers”) and proper administration of justice within those forums. Proper administration of justice in turn required that trials be presided over by impartial magistrates (not “judges dependent on his will alone”), in venues subject to public scrutiny (not “beyond seas”), and with independent decision-makers who could be trusted to render impartial verdicts (not “depriving us in many cases of the benefits of trial by jury”). Insofar as the Declaration addresses judicial independence, it emphasizes freeing judges from subservience to an unaccountable executive whose interests differed from those of the general public. The Declaration thus left open whether making the judiciary answerable to the people, either directly or through their elected representatives, posed the same problems for the rule of law or for the impartial administration of justice. Or, put differently, it left open the relationship between republicanism and judicial independence.

Some early state constitutions contain stirring rhetoric on judicial independence. The Massachusetts Declaration of Rights of 1780, for instance, proclaimed it “the right of every citizen to be tried by judges as free, impartial, and independent as the lot of humanity will admit,” and the Maryland Declaration of Rights of 1776 noted that “the independency and uprightness of Judges are essential to the impartial administration of justice, and a great security to the rights and liberties of the people.”5 Although proponents of judicial independence never tire of quoting such provisions, the institutional arrangements under eighteenth-century state constitutions emphasized judicial accountability to state legislatures, as “short terms with election and reelection voted by the same lawmakers who set rates of compensation and paid their salaries made judges more dependent than independent.”6 Indeed, those Massachusetts “judges as free, impartial, and independent as the lot of humanity will admit” could be removed upon a vote of two-thirds of the state legislature. In emphasizing judicial accountability to state legislatures, early state constitutions “represented the culmination of what the colonial assemblies had been struggling for in their eighteenth-century contests with the Crown.”7

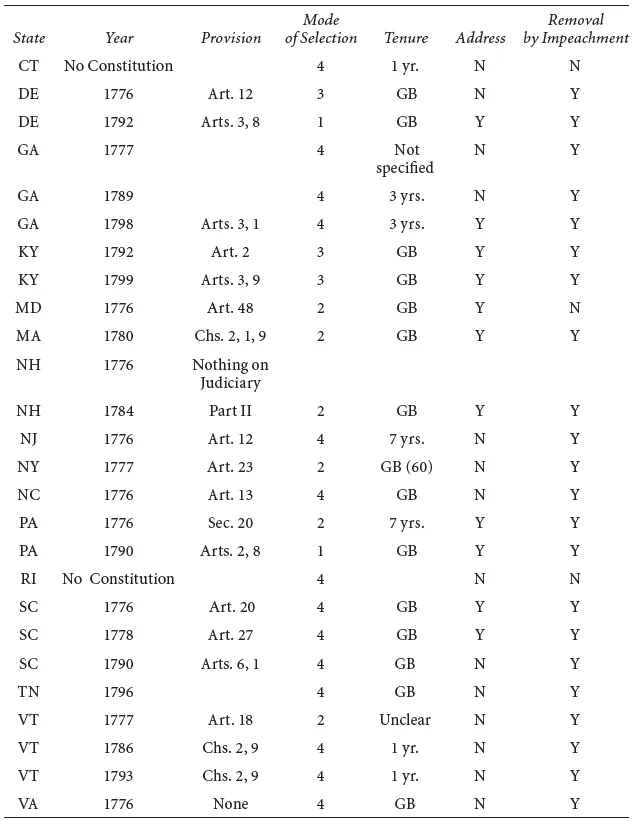

State judges in the decades after Independence might be appointed by the executive, by the legislature, or by some combination of the two, but state legislatures generally dominated judicial selection (see Table 1.1).8 This legislative dominance is explicable on republican grounds. In most states, only legislators were directly elected by the people, and this—combined with their short term of office—encouraged the belief that the legislature embodied the people, whereas other branches did not. Given this understanding, legislatures seemed the safest repository of the appointment power. In addition, legislative dominance was a response to Americans’ suspicion of executive power in general and of the executive appointment power in particular. As Gordon Wood has noted, “The power of [executive] appointment to offices” was perceived as “the most insidious and powerful weapon of eighteenth-century despotism.”9 Thus, none of the initial state constitutions gave the governor acting alone the power to appoint judges. By 1800, two states—Delaware (1792) and Pennsylvania (1790)—authorized unilateral gubernatorial appointment, but seven continued to lodge the appointment power exclusively in the state legislature. The remaining states allowed the governor to appoint judges but required that appointments be confirmed by an executive council or the legislature. Even where governors participated in the selection process, their control over the composition of the bench was limited. For in several states the governors themselves were largely creatures of the legislature, chosen by it for short terms and dependent on it for their continuation in office, and this undoubtedly influenced their choices.

TABLE 1.1 State Judiciaries in the Eighteenth Century: Selection and Tenure*

* Excluding justices of the peace

1 = Gubernatorial appointment

2 = Gubernatorial appointment and council confirmation

3 = Gubernatorial appointment and legislative confirmation

4 = Legislative appointment

5 = Election

GB = During good behavior

(60) = Retirement age of sixty

Once selected, judges remained under legislative scrutiny. “The Revolutionaries had no intention of curtailing legislative interference in the court structure and in judicial functions, and in fact they meant to increase it.”10 During the colonial era, popular assemblies with some regularity “restored [losing litigants] to the law” by granting them a new trial, which served as a check on abuses by unelected judges. After Independence, those who lost in court might still appeal to the legislature for redress, and legislators could order new trials or pass private bills providing them with the compensation denied them at trial. This practice continued into the nineteenth century, with the Rhode Island Legislature overturning adjudicated verdicts almost to the Civil War.11

Judges who issued unpopular rulings might be called before the legislature to explain their decisions. In 1786, for example, after the Rhode Island Supreme Court invalidated a law requiring creditors to accept paper money in payment for debts, its members were summoned before the legislature, and although the legislature took no disciplinary action, it refused to reappoint all but one of the justices when their terms expired.12 When all else failed, a legislature might get rid of judges by enacting “ripper bills” that abolished the judges’ positions or the court on which they sat because the structure of state court systems typically was not entrenched in the state constitution. Thus in 1807, after the Ohio Supreme Court struck down a law extending the jurisdiction of justices of the peace, the legislature passed a resolution depriving the offending justices of their positions when their terms expired.13 New Hampshire twice legislated out of office all justices of the supreme court by repealing the statute that created the tribunal and establishing another court in its place.14 In New York in 1821, a new constitution reduced the membership of the supreme court from five to three, and the incumbents’ positions were terminated when the constitution went into effect.15 And in Kentucky in 1823, the legislature, after failing to muster the two-thirds vote necessary to impeach justices who had invalidated a law providing for debt relief, abolished the supreme court and created a new one with new judges.16

State constitutions guaranteed the people’s representatives control over judges’ continuation in office. One-third of eighteenth-century state constitutions established short terms of office for judges, ranging from one year in Vermont to a high of seven years in New Jersey and Pennsylvania (1776). Obviously, in those states the process of periodic reappointment, in which legislators played the central role, determined whether judges would continue in office. The remaining two-thirds of eighteenth-century state constitutions, reacting to the British imposition of service during the pleasure of the Crown, provided for judicial tenure during “good behavior.” During the last quarter of the eighteenth century, one can detect a slight movement toward longer judicial terms—for example, Georgia in 1789 increased the term of office to three years, and Pennsylvania in 1790 adopted tenure during “good behavior.” But even in the eleven states in which, by 1800, judges served during “good behavior,” legislatures scrutinized the judiciary. We understand “good behavior” today as a synonym for life tenure, but during the early decades of the Republic, it was understood as a standard of conduct enforceable by the legislature.17 Indeed, as a contemporary commentator noted, the nebulous character of that standard virtually invited legislators to apply it “according to disaffection on the one Hand; or Favour on the other.”18

The legislature might act against “misbehaving” judges through impeachment, and the grounds for impeachment under early state constitutions were considerably broader than those under the federal Constitution.19 States that defined impeachable offenses in their constitutions did so expansively. Thus New York (1777) and South Carolina (1778) permitted impeachment for “mal and corrupt conduct”; New Hampshire (1784) for “bribery, corruption, malpractice, or maladministration in office”; and New Jersey (1776) for “misbehavior.”20 Other states declined to define—and thereby limit—the grounds for impeachment. For example, in constitutions written after the US Constitution had limited impeachable offenses to “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors,” Georgia (1789), Kentucky (1799), and Tennessee (1796) all provided for impeachment without specifying what offenses justified removal.

Several states supplemented impeachment with provisions authorizing the governor to remove judges upon address by two-thirds of the state legislature, with the gubernatorial role typically more ministerial than discretionary. Rather than merely duplicating impeachment, removal by address offered an additional—and potentially more far-reaching—weapon for legislative control.21 For one thing, the “address did not have to allege willful or criminal misconduct. It needed only a favorable vote by both houses, not an investigation or trial.”22 Thus, judges were not guaranteed the basic elements of due process before they were removed. They did not have an opportunity to retain counsel, to cross-examine those accusing them, or to call their own witnesses. Early state constitutions did not even require a specification of the grounds for removal, although some later state constitutions mandated that the basis be “stated at length in such address, and on the journal of each house.”23 Thus, the inclusion of removal by address in state constitutions potentially came close to service during the pleasure of the legislature (or at least an extraordinary majority of the legislature), although the guarantee of tenure during “good behavior” implied that some misconduct had to be alleged. Address allowed legislators to hold judges accountable not only in cases of clear wrongdoing, as might be reached by impeachment, but even in instances where their performance could not be characterized as “any misdemeanor in office.”24 The Kentucky Constitution of 1799 made this clear, authorizing removal of judges by address “for any reasonable cause, which shall not be sufficient ground for impeachment.”25 So too did the origins of the practice in England, where address served as a mechanism for inducing the king to remove unpopular ministers, serving as “a vote of censure and no confidence.”26 In rejecting removal of federal judges by address, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 indicated their understanding that removal by address potentially had greater reach than did impeachment.27 Thomas Jefferson agreed with the analysis but not the conclusion. He favored a constitutional amendment to permit removal of federal judges by the president upon address by Congress, insisting that “in a government founded on the public will, [judicial independence] operates in an opposite direction, and against that will.”28

The Removal of Judges

Although state legislatures maintained close oversight over the judicial branch, their removal powers threatened judges’ decisional independence only if those powers were used to influence the substance of decisions or to penalize judges for their rulings. Often this was not the case. For example, New Jersey in 1782 impeached and removed two judges for corruption, and Mass...