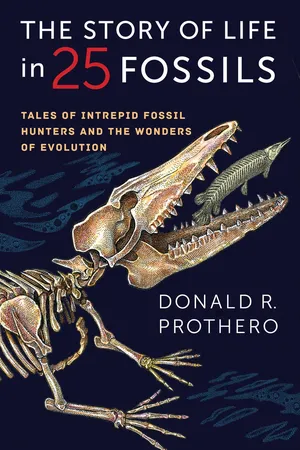

![]()

01 | THE FIRST FOSSILS | CRYPTOZOON |

PLANET OF THE SCUM

If the theory [of evolution] be true, it is indisputable that before the lowest Cambrian stratum was deposited, long periods elapsed…and the world swarmed with living creatures. [Yet] to the question why we do not find rich fossiliferous deposits belonging to these earliest periods…I can give no satisfactory answer.

CHARLES DARWIN, ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES

DARWIN’S DILEMMA

When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, the fossil record was a weak spot in his argument. Almost no satisfactory transitional fossils were known, including none of the fossils discussed in this book. The first good one to be discovered was Archaeopteryx in 1861 (chapter 18). Even more troubling was the absence of any fossils that date to before the earliest period of the Paleozoic era, known as the Cambrian period (beginning about 550 million years ago [see frontispiece]). Of course, the fossil record was poorly known in the mid-nineteenth century, and it had been only 60 years since anyone had begun to note the sequence of fossils in detail. Still, Darwin was puzzled that in the few “Precambrian” beds below the earliest trilobites, there were no fossils that showed the transitions from simpler animals to trilobites and the other organisms of the Cambrian. Darwin said it all very clearly in the epigraph to this chapter.

Darwin attributed this puzzling lack of fossils to the “imperfection of the geological column” and the unlikely possibility that most organisms ever fossilize. To a large extent, he was correct. He posed this question to his scientific peers, who for the next century tried desperately to find any kind of fossils older than the trilobites.

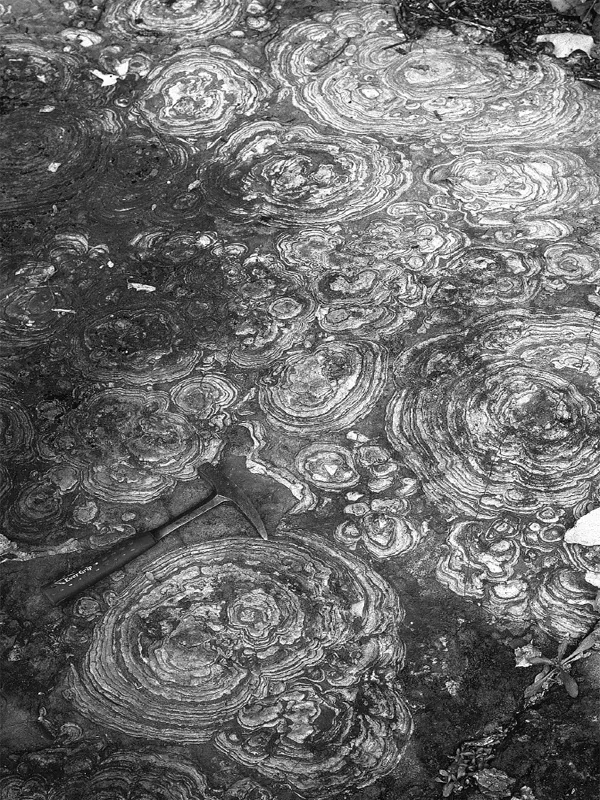

Figure 1.1

Reconstruction of the shallow tide pools on Earth as they looked for more than 80 percent of life’s history, from 3.5 billion years ago to 550 million years ago. The only visible forms of life were mounds and domes of cyanobacterial mats, known as stromatolites. (Painting by Carl Buell; from Donald R. Prothero, Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters [New York: Columbia University Press, 2007], fig. 7.1)

Many geologists already knew the problems with finding fossils that date to the Precambrian. Most Precambrian rocks are so old that they are deeply buried and long ago were heated and put under intense pressure that turned them into metamorphic rocks, so any fossils were likely to have been destroyed. Most rocks that are truly ancient are also likely to have been eroded away, another form of destruction. Even where they are relatively well preserved, the oldest rocks are usually buried under a thick layers of much younger rocks, so there are very limited exposures of them almost anywhere on Earth. All these factors conspired against the idea that we could just easily pick up fossils from Precambrian rocks, as we could from Cambrian rocks.

Still, there was more to the problem than this. It turns out that the conditions in the Precambrian (especially, little or no oxygen and no ozone layer) seem to have prevented early organisms from forming shells or other hard parts for a very long time. Instead, for 2 billion years, the world was dominated by mats of bacteria and (much later) algae, growing in the shallow waters of the shorelines and coating the rocks (figure 1.1). There are fossils in Precambrian rocks, only most of them are microscopic and cannot be seen without carefully grinding thin slices of rock on a microscope slide to see them at high magnification. To a field geologist, there are no visible fossils in most Precambrian rocks.

Nevertheless, there are many noticeable features in these rocks that people had been arguing about for a long time. For example, a structure that looks like a weird radiating pattern of grooves was described in 1848 by pioneering Canadian geologist Sir John William Dawson as Oldhamia (figure 1.2). He thought that it was the fossil of some kind of polyp. Yet Irish geologist John Joly was walking down a frozen muddy trail and found a similar pattern formed by ice crystals in the mud. In 1884, he argued that Oldhamia was just a feature produced by ice crystals, and not a fossil. More recently, scientists have reevaluated Oldhamia, and now they conclude that it is the burrow of some kind of worm, so it is evidence of life after all—but this example shows how easily people can be fooled when they are so desperate to find signs of life in the Precambrian.

Figure 1.2

An original illustration of Oldhamia. (Redrawn by E. Prothero)

Another “creature” was discovered in 1868 by the legendary biologist (and Darwin’s defender) Thomas Henry Huxley, who noticed a slimy “organism” in jars of mud recovered from the deep sea in 1857. He named this “creature” Bathybius haeckeli (the genus name from the Greek for “deep life,” and the species name in honor of German biologist Ernst Haeckel). However, prominent British scientist Charles Wyville Thomson was not impressed, and he looked at the specimens and thought they were just fungal decay products. Another biologist, George Charles Wallich, proposed that the “organism” was the product of chemical disintegration of organic materials.

For this and many other reasons, Wyville Thomson and many other British scientists organized and funded the voyage of HMS Challenger from 1872 to 1876. The Challenger, a fully rigged sailing ship with steam power as well, was one of the first to actually conduct round-the-world oceanographic voyages. At that time, the British scientific community had no idea what the bottom of the ocean was like and thought that trilobites were still hiding in the deep oceans. They also sought answers to what Bathybius really was. The Challenger crew took more than 361 deep-ocean mud samples, without finding one Bathybius. Then the ship’s chemist, John Young Buchanan, looked at some older samples and found something that resembled the mystery “slime.” When he analyzed it, he realized that it was merely a reaction product of calcium sulfate with the alcohol used to preserve the sample. Wyville Thomson sent a polite letter to Huxley informing him about Buchanan’s identification of the “organism.” To his credit, Huxley published a letter in the journal Nature acknowledging his mistake. In 1879, at the 1879 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Huxley took full responsibility for his error.

Yet another false alarm came in 1858, the year before Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published. Legendary Canadian geologist Sir William E. Logan (later director of the Geological Survey of Canada) found some unusual rocks from the banks of the Ottawa River near Montreal. Logan showed the specimens to scientists over many years, but most were unconvinced that they were proof of early life. The specimens then became the cause of Dawson, one of the most prominent scientists in Canada. In 1865, Dawson named Logan’s layered structure Eozoon canadense (dawn animal of Canada) (figure 1.3). Dawson thought it was the fossilized remains of a huge foraminiferan (a group of amoeba-like, single-celled creatures that live in the oceans and make calcite shells). He called it “one of the brightest gems in the crown of the Geological Survey of Canada.” Yet not long after that pronouncement, other geologists looked at the specimens more closely and at the geological setting. They found that Eozoon was just metamorphic layering of the minerals calcite and serpentine, not a fossil. The clincher was the discovery in 1894, near Mount Vesuvius in Italy, that the heat of volcanism can produce a similar structure in rocks.

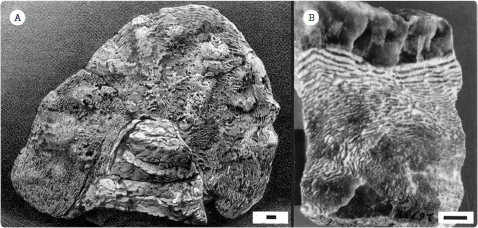

Figure 1.3

Eozoon canadense (dawn animal of Canada): (A) illustration in Dawson’s Dawn of Life; (B) the holotype specimen at the Smithsonian Institution. Scale bars = 1 centimeter. ([A] from John W. Dawson, The Dawn of Life [London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1875]; courtesy J. W. Schopf)

CRYPTOZOON: YET ANOTHER FALSE ALARM?

Oldhamia, Bathybius, Eozoon. These and many other pseudofossils are among the discredited examples of Precambrian “life” that were once touted as the original ancestors of living things, and then debunked. Today, only historians of geology remember them.

In retrospect, it is easy to see why people were fooled. Most geologists learn early in their careers that the geologic landscape is full of pseudofossils, objects that appear to be possible fossils until you look closer (and know what to look for). Almost every amateur rock hound is fooled by the very plant-like patterns of pyrolusite dendrites, a mineral structure of manganese oxide that looks just like a branching fern. The most common pseudofossils are concretions, which are grains of sand or mud cemented together in a variety of shapes. Most are shaped like spheres or odd blobs, but many have bizarre forms that untrained amateurs visualize as a “fossil brain” or a “fossil phallus” or many other shapes that fool our tendency to see a “pattern” where there is none.

Like seeing “castles” in clouds or “animals” among the stars, humans are hardwired to infer meaning and pattern in nearly any collection of random images, a phenomenon known as pareidolia, or “patternicity.” Thus experienced geologists learn to be very skeptical of interpreting just any odd-shaped rock as a fossil, and it takes years of experience to tell one from another. This was especially true in the early days of geology, when most sedimentary structures, and structures formed by burrowing, had not yet been defined and distinguished from true body fossils.

The next important figure in this story was Charles Doolittle Walcott, a self-trained geologist with the United States Geological Survey (figure 1.4). He had but ten years of schooling and never earned a degree, but received many honorary degrees later in life. Nevertheless, Walcott went on to become one of America’s most important scientists in the early twentieth century. Almost single-handedly, he documented the entire Cambrian record of North America from New York State to the Grand Canyon, and became the founder of the study of Precambrian fossils as well. Later in life, he was legendary for multi-tasking on a scale scarcely imaginable today. He was director of the U.S. Geological Survey (1894–1907), and then was promoted to secretary (director) of the Smithsonian Institution (1907–1927), while also serving as president of the National Academy of Sciences (1917–1923). He also served as president of both the American Philosophical Society and (like Dawson) the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Despite this incredible administrative workload, he also managed to eke out a few weeks each summer to continue his grueling fieldwork in the Rocky Mountains and Colorado Plateau, describing huge mountains of Cambrian rock and amassing gigantic collections of fossils that he somehow found time to describe and publish. It was on one of those field trips that he accidentally stumbled on the Burgess Shale, a Middle Cambrian gold mine of soft-bodied fossils (chapter 5). He described these fossils superficially, but did not have time to really examine them, given his overcommitment to a crushing workload.

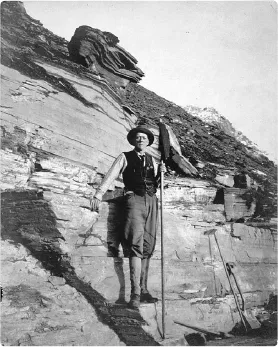

Figure 1.4

Charles Doolittle Walcott, working in the Burgess Shale quarry in 1912. (Photograph courtesy Smithsonian Institution)

Walcott began his career working for the legendary James Hall, the first chief geologist and paleontologist of New York State. On a vacation in Saratoga, Walcott took a short field trip to Lester Park, only 5 kilometers (3 miles) west of Saratoga Springs. There, he was impressed by a layered structure in the very ancient Precambrian rocks he was studying (figure 1.5). In 1878, when he was only 28 years old, he began to describe in detail these layered, dome-like or cabbage-like structures, which Hall named Cryptozoon (hidden life) in 1883. They were common in nearly every Precambrian rock, so Walcott was convinced that they were the first evidence of life ever fossilized.

Most other scientists were very skeptical, however. Layered structures are very easily produced by natural means without organisms being involved, such as the layered structures in metamorphic rocks that fooled Dawson into identifying the “fossil” Eozoon or those formed during slow crystallization from a solution or by metamorphic foliation. The prominent botanist Sir Albert Charles Seward, the most influential man in paleobotany for many years, was a major critic of Cryptozoon. He correctly pointed out that there were no organic structures of plants or anything else preserved, making the case for Cryptozoon very shaky.

Nevertheless, many geologists were describing these layered, dome-like or cabbage-like structures, which were the only megascopic feature of most Precambrian rocks, and giving them names. In addition to Cryptozoon, there was another genus named Collenia for a differently shaped layered structure, and the name Conophyton was applied to layered structures with a conical rather than domed shape. Soviet geologists, who had huge areas of unmetamorphosed Precambrian rocks to study in Siberia, were especially fond of naming every shape of these layered structures. All these features were given the broader category name stromatolite (layered rock), even though most geologists were not certain that they were biologically produced.

Figure 1.5

The Lester Park stromatolites, called Cryptozoon by James Hall and Charles Doolittle Walcott. The top of these cabbage-like specimens were sliced off by a glacier, exposing their concentric internal layering. (Photograph by the author)

EUREKA!

For the first half of the twentieth century, the geological and paleontological community was deeply divided about what stromatolites were. Study after study had produced no signs of organic material or preserved cells in layers, so the case seemed weak. As long as no extant example of these structures was living and growing, there was no convincing evidence to silence the doubters.

In 1956, geologist Brian W. Logan of the University of Western Australia in Perth and some other geologists were exploring the northern coast of Western Australia. Logan and his colleagues came across a lagoon known as Shark Bay, about 800 kilometers (500 miles) north of Perth. When the tide went out in Hamelin Pool, on the south...