1

SHELTER WRITING

Desperate Housekeeping from Crusoe to Queer Eye

The history of the novel is full of women burdened by a stifling or terrifying domesticity. From the bored Emmas (Woodhouse and Bovary) to the incarcerated Bertha Mason, they are driven to various extremes by too much house, by interior spaces too cushioned or confining. In contrast to those made desperate by an excess of domesticity, the figures that concern me in this chapter embody an opposite logic: they are driven to domesticity—the refuge of four walls, the consolation of a table—by desperate circumstances. Taking up a range of texts (many of them novels), I focus on protagonists who, far from being trapped inside, are outcasts or castaways of some kind. For these characters, who are outsiders to polite society and at times literally out of doors, domestic spaces and domestic labor mean neither propriety and status nor captivity and drudgery but safety, sanity, and self-expression: survival in the most basic sense. The blow-by-blow accounts of their efforts to make and keep house exemplify the mode I call “shelter writing.” It is a mode that may center on anyone whose smallest domestic endeavors have become urgent and precious in the wake of dislocation, whether as the result of migration, divorce, poverty, or a stigmatized sexuality. This chapter theorizes forms of shelter writing and analyzes, by way of illustration, a text in which domestic shelter is lost, longed for, and finally recreated by a narrator who is transgendered.

My exemplary text is Stone Butch Blues (1993) by Leslie Feinberg, a writer known for her essays and activism on transgender issues as well as for this self-evidently autobiographical novel. The book is narrated in the first person by Jess Goldberg, a masculine woman from a working-class family in Buffalo, New York, who comes of age in the 1950s. Strongly male-identified, Jess briefly considers transitioning to male, and during this time she passes as a man. Throughout the novel, we see her working alongside men and other butches on the factory floor, riding her motorcycle, and drawn to feminine women. We also see her rejected and brutalized from an early age for so radically controverting gender norms. No wonder Judith Halberstam devotes a central chapter of Female Masculinity to Feinberg’s title character, stressing Jess’s working-class masculinity and defending her “stone” sexuality. My own reading builds on and supplements this emphasis by bringing out other, complicating aspects of Jess: what I elsewhere identify as her “butch maternity” and also, of particular interest here, her butch domesticity.1

The relevant passage occurs toward the end of Stone Butch Blues, shortly after Jess has set out from Buffalo and washed up on the shores of Manhattan. For a month she’s been crashing in makeshift, semipublic quarters and bathing in Grand Central Station, until at last she has the money for a real apartment. Handing over her cash to an indifferent super, she is free to take the measure of her new place:

I locked the door of my apartment and turned to look around. It needed paint: yellow for the kitchen, sky blue for the bedroom, creamy ivory for the living room. I needed rugs. And dishes, silverware, pots and pans. Cleanser for the sink.

I opened my duffel bag to look for a pad and pen to make a list. There was the china kitten that Milli had left me. I placed it gingerly on the mantle in the living room.…

I decided to buy some yellow calico curtains for the living room windows, like the kind Betty had made for my garage apartment. I glanced at the door once more to make sure it was locked.2

A few pages later, the day-by-day account of intensive nesting continues:

Every time I got a paycheck I used part of it on my apartment. I spent one whole weekend spackling the cracks in my walls and ceilings. As I applied paint to each room with broad strokes my spirits lifted.

On my most ambitious weekend I sanded all the wood floors. Then I started from the furthest corner of the apartment and polyurethaned myself out of the door. That night I slept at a 42nd Street theater again—just for one more night!

The floors were dazzling. It added a new dimension underfoot, as though the ceilings were raised, or the apartment had grown in size.

I found a black Guatemalan rug at a flea market. It had tiny flecks of white in it. I unrolled it in my living room and stood back to look. It reminded me of the night sky filled with stars.

Gradually I bought furniture—a sturdy couch and reading chair, a mahogany kitchen table and chairs. At the Salvation Army I found a bed—the head and footboards were ovals carved out of cherry. I went crazy buying sheets at Macy’s.…

I bought thick, soft towels and fragrances for my bath that pleased me.

And then one day I looked around at my apartment and realized I’d made a home.3

I offer these paragraphs by way of general introduction to the meanings, satisfactions, embarrassments, and divergent uses of shelter writing. Often, as here, it is embedded in a longer text: a few pages lingering over the shaping of a domestic space; part of a chapter detailing the pleasures of securing and supplying, ordering and adorning, taking a room from mess to thoughtful arrangement. Someone rigs up a shelter, hauls in scraps, and refurbishes them for household use; now he piles pillows on a mattress, pulls a blanket straight; next she arranges crockery in a cupboard, each piece a smooth weight in her hand; later she cleans from top to bottom, restoring order and brightness; and every day there are soothing, sometimes wearying rounds of neatening and freshening. Practical, aesthetic, and perhaps metaphysical desires coalesce in these passages. Memory comes into play (Milli, Betty, star-filled nights) along with desire. Ideological as well as emotional agendas are advanced. Small, specific, oft-repeated actions, meaningful in themselves, indicate larger and more profound ones—Mrs. McNab and Mrs. Bast, for example, scrubbing against death and decay at the heart of To the Lighthouse.

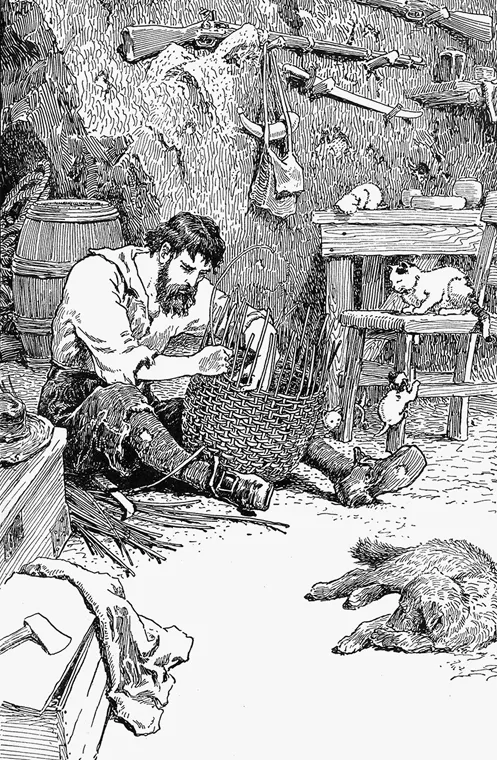

FIGURE 1.1 Charles Copeland, “Robinson Makes Baskets.” (From Daniel Defoe, The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, ed. W. P. Trent [Boston: Athenaeum, 1916]. Courtesy of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

Of course, the ur-shelter text is Robinson Crusoe, in which Crusoe structures time as well as space, saving his skin while preserving his reason, by methodically devising a domesticity of his own (figure 1.1). For while Crusoe has often been taken as a prototype of the explorer or entrepreneur, I agree with Pat Rogers in “Crusoe’s Home” (1974) that Daniel Defoe’s hero is, above all, a homemaker, busying himself with an array of domestic arts from building and furnishing a shelter to making pots and baking bread.4 What we are most fascinated and moved by, what we recall if we recall anything about this novel, are the almost technical descriptions, many of them in journal form, of the household tasks Crusoe undertakes not simply to survive but also to create, as he puts it, “some order within doors”:

Dec. 11. This day I went to work … and got two shores or posts pitched upright to the top, with two pieces of boards a-cross over each post; this I finished the next day; and setting more posts up with boards, in about a week more I had the roof secured, and the posts, standing in rows, served me for partitions to part of my house.

Dec. 17. From this day to the twentieth I placed shelves, and knocked up nails on the posts to hang every thing up that could be hung up, and now I began to be in some order within doors.

Dec. 20. Now I carry’d every thing into the cave, and began to furnish my house, and set up some pieces of boards, like a dresser, to order my victuals upon, but boards began to be very scarce with me; also I made me another table.5

In this discourse, characters use broom and hammer, muscle and imagination to stay death, cling to life, or simply keep house. Sentences devoted to homemaking and housekeeping occur, though largely unremarked, throughout the history of the novel from Defoe to writers like Charlotte Brontë, Elizabeth Gaskell, Virginia Woolf, Radclyffe Hall, and on up through Feinberg. It should not surprise us, then, to be told that Woolf’s Mrs. McNab and Mrs. Bast salvage a basin, a tea set, and … the works of Sir Walter Scott. A central project of the realist novel—its production of interiority—is effected in part through the concrete, systematically detailed domestic gestures of a Robinson Crusoe or a Jess Goldberg. Descriptions like Defoe’s and Feinberg’s are intrinsic to the meaning and inextricable from the grain of the genre.6 They are not, however, confined to it. In contemporary culture we find instances of shelter writing, broadly speaking, in media such as house magazines and reality television. House Beautiful (1896–present), Martha Stewart Living (1990–present), Queer Eye for the Straight Guy (2003–2007), and Love It or List It (2008–present) all offer versions of this domestic microdrama: the step-by-step creation, restoration, or transformation of one’s living space. Nor is it surprising that we find such a scenario more often on the small than on the large screen. Television’s cheerful traffic in the seemingly insignificant, its penchant for the domestic, and its commitment to repetition conduce quite naturally to scenes of self-discovery in a newly Windexed mirror. Before returning to the passage from Stone Butch Blues, I want to consider at some length the theoretical parameters and political implications of this discourse about dwelling.7

TOPOGRAPHY

Of interest here are both content and form. While attending to shelter and shelter making as things and actions referenced, I would also identify the generic attributes of shelter writing. Since most of my examples are literary, they might seem to fall under the rubric of description (ekphrasis in classical terms) and, more specifically, topography, or the description of landscapes and places. Translating the visual into the verbal, concerned with space rather than time, representing objects that exist simultaneously rather than events that occur sequentially, description is often posed against narration.8 Yet theorists of this mode, like Michel Beaujour, note that descriptions of what appear to be static, ornamental scenes shade easily into those of movement and function. Descriptions of gardens, for example, captured as if on canvas, dissolve into descriptions of flowers swaying and gardeners watering, a different kind of description, if not a different register altogether.9 Certainly this is true of my homemaking examples, in which interior description functions not apart from but as narrative, depicting interiors as they are actively envisioned, handled, and renewed. More important, such descriptive passages qualify as shelter writing only in a particular narrative context—one involving a history of deprivation or difficulty regarding shelter.10

Descriptions are suspected, too, of fetishizing the detail, thereby not only losing the narrative thread but also causing characters to recede, eclipsed by unimportant particulars, in effect reversing the proper relation between figure and ground.11 But the kind of description I am specifying here, however in love with itemizing particulars, does not actually stray from so much as stage the protagonist in her or his relationship to domesticity. Passages devoted to walls and ceilings, pots and pans, seemingly digressive and even “skippable,”12 contribute crucially to the establishment and development of characters. Indeed, as I began by saying, the mode I am defining turns on a protagonist whose abjection gives peculiar significance to her or his interaction with domestic objects and occupation of domestic spaces. There is one last point to make about shelter writing as descriptive writing, in the impurest sense. According to Beaujour, description is best understood, despite its seeming empiricism, as a register of fantasy, the rendering of a dreamscape. “As the multifaceted mirror of Desire, description bears only an oblique and tangential relationship to real things, bodies and spaces. This is the reason why description is so intrinsically bound up with Utopia, and with pornography.”13 My subset of shelter writing does, it is true, involve both dreaming and desire, and these may have an erotic as well as a political cast. At the same time, I want to insist equally on its status as a materialism or, more accurately, a realism—a mode very much invested in highly specified, physical depictions of things/bodies/spaces and their function in a given text on a literal as well as a figurative level. This is especially true insofar as the descriptions show daily, repetitive, and, in the case of housekeeping, ostensibly nonproductive physical labor as valuable in and of itself.

TOPOANALYSIS

As I have mentioned, one of the most helpful intertexts for my notion of shelter writing is The Poetics of Space (1958), a meditation on the emotional meanings of interiors by Gaston Bachelard. Like Bachelard, I attend primarily to the house imagined as a “felicitous space,”14 a space that protects and consoles. “Hostile space is hardly mentioned in these pages” (xxxvi), he tells us in his introduction. Instead, his is a poetics of the safe, snug interior; the house evoking a nest, cradle, or shell; the house whose predominant affect is maternal. According to Bachelard, this sense of the house as refuge is only heightened when tested by the elements—by snow, for example, or by storm. When the house is besieged, it becomes, in our imaginations, more intimate, more fiercely protective (38–47). His work encourages us, moreover, to see the domestic space as “the topography of our intimate being” (xxxvi). Engaging in “topoanalysis,” he takes us on an affectionate tour of its most hidden recesses: its cellars and garrets, its nooks and crannies, and the smaller containers contained therein—drawers, chests, and wardrobes, or what he charmingly calls “the houses of things” (xxxvii). The house for Bachelard is therefore at once what encloses us and what we enclose, a figure for the womb and a figure for the psyche, the place in which we dream and a set of images for what is dreamed. In either case, the house in The Poetics of Space is never an impersonal monument or sterile showcase but is always inhabited, touching us and responsive to our touch.

For me, too, as I have said, descriptions of interior spaces do not, as early critics of description feared, overshadow the people who live there. On the contrary, in my account they serve ...