![]()

1

THE CONCEPT OF SPORT

Aristotle hypothesized that the “unmoved mover” was the highest state of being. Many other early philosophers—Buddha, for instance—believed something similar. This may seem counterintuitive to us. Movement is, after all, essential to life. In everyday speech we associate movement with both beauty and capability: a person runs like a gazelle; a cheetah is agile and capable and moves quickly, gracefully, forcefully.

So why did Aristotle and others suggest that the unmoved mover is the highest state? It’s because movement was tied to a dualism, a concept now mostly outdated thanks to our understanding of evolution and the normal functions of the nervous system. Movement was thus seen as a kind of privation: less mind and more body. Nevertheless, Aristotle thought like a biologist, capturing and cataloguing living things. Indeed, as human beings, we do a lot of cataloguing, and we do it quite easily because from a young age we are generally taught to navigate the world through categories. Thus we are quick to classify objects in terms of the kinds of things we believe they are.

Much of our categorization is tied to action, with sport often considered the quintessential moment of action. But sport is not just action; there is no dualism of mind and body. Whatever one means by “mind” (of which there is no univocal definition), sport is rich in it. And running through sport is thought—embodied thought (Varela, Thompson, and Rosch 1991), structured and practiced through well-worked habits (Peirce 1878).

Movement is replete with thought. While movement is not the essence of sport, it is a fundamental feature of it: think of the swing of a baseball bat, the bunching and unbunching muscles of the sprinter’s calves, the tension in the still moment before a golfer sinks the ball in the hole, the alignment of the body in a single plane as the archer pulls back on the bow. All this is movement, but it is movement organized and driven by thought, purpose, and intent. And while sport always involves movement, not all movement is sport.

In this chapter, I begin with a context for understanding sport, given our capabilities and our cultural evolution: sport lies in the continuous fluidity between biology and culture.

WHAT IS SPORT?

When is movement considered a sport? People tend generally to agree on what is sport and what is not and even to share the same sense of ambiguity about the classification of certain activities. Rather as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said of obscenity in 1964, we know it when we see it. But there is no one feature that defines sport, except perhaps that it is competitive and that there are always winners and losers. Even in elementary-school athletics where everyone goes home with a trophy, the children are always—and sometimes cruelly—aware of who won and who lost. But sport is also a type of game, and Wittgenstein (1953) and later game theorists have identified a family of properties that loosely defines a game. One feature games have in common is that there are rules to be followed and a language or logic to understanding the activities and participating in them. There may be little in common between skiing and soccer, between snowboarding and hockey, but they all are rule based and have winners and losers based on those rules. Indeed, a signal feature of those activities that some people would prefer not to regard as true sports (although no one doubts that their practitioners are true athletes), activities such as figure skating, is that they contain subjective elements such as “artistry” that can be decided only arbitrarily by judges and not by a strict, clear application of the rules.

While all sports are a type of game, not all games are sports. Chess and Scrabble are conventionally considered to be games but not sports, even though they can be played competitively and there are clear winners and losers.

One reasonable view about how to distinguish play from sport (Guttmann 1978) takes the list of all things we consider to be play and pares it down into games, contests, and then sports. Play includes spontaneous play and organized play (games). Games then can be divided into noncompetitive games and competitive games (contests). Finally, contests can then be categorized by intellectual or physical contests, and the latter type of contest is what we consider to be sport.

To be truly considered a sport, an activity’s practitioners must exhibit some sort of physical prowess, some feat of practiced, intentional, applied movement that reaches beyond the ordinary. They must be athletes.

THE HISTORY OF SPORT IN A NUTSHELL

We know games are very old. What appear to be gaming boards first surface in the Neolithic period. It’s hard to believe that sport does not have an even older history. Archaeological evidence suggests that wrestling is the first publicly expressed, original sport; this is not surprising, since rough-and-tumble play is a core feature in the lives of many mammals and certainly of primates.

The first truly organized sporting events seem to have been competitions associated with Greek religious festivals honoring gods, commemorating mythical events, and marking seasonal changes, starting about 2,500 years ago (Guttmann 1978, 1991, 1992, 2004). The origin of the ancient Olympic Games is speculative, but they may have begun as a commemoration of Zeus’s defeat of Kronos in a wrestling match.

The original Olympic Games are merely the best known of such festivals (Guttmann 1992), which were held throughout ancient Greece. Other notable examples of athletic festivals include the Pythian (582 BC) and the Nemean (579 BC) Games that were held to celebrate Apollo as well as the Isthmian Games to celebrate Poseidon (582 BC) (Guttmann 1978, 2004). As well as seasonal festivals, sporting events were associated with life-cycle markers, especially funerals. The Iliad, for instance, describes the funeral games that Achilles held in honor of his friend Patroclus, who was killed in the battle for Troy. The actual sports played at such festivals were many, including footraces of different lengths, boxing and wrestling events, horse races, and the pentathlon (Guttman 1978, 2004).

The ritual aspects of such games—the competition and the spectacle—must have fueled excitement. Ancient Greek audiences were interested in form and beauty and excellence. Though statistics emerged only in the seventeenth century within the context of state records (births, marriages, deaths, etc.,), keeping records of sporting events, perhaps noting times and comparing trends, and certainly following the successes and failures of specific athletes, goes back to the ancient Olympics. The emphasis was on form, not experiment, and certainly not probability. The organization of numbers is infused in all thinking, and it is one of the primary ways we keep track of events.

BALL GAMES

Balls, made of rubber in Mesoamerica and of leather and textiles in other parts of the world, feature in ancient games. Pre-Columbian ball courts in the Americas survive at a number of sites, and the balls and games are depicted in detail in Mesoamerican art (Stone 2002). Indeed, many pre-Columbian ball games in Latin America are believed to have involved the human sacrifice of the losers or possibly of the winners (as the most fitting gift to the gods). Balls are also central to many loosely organized community-based games, for example, Scotland’s ba’ game (see below), in which local friendly and not-so-friendly rivalries are hashed out.

As a New York City child I played a lot of such casual ball games with the other neighborhood kids: punch ball, stick ball, throwing the ball off the stoop. Little did I know in what a long tradition I was participating. Stick ball, which involved hitting a rubber ball in the street, with marked sewers as goals, was an after-school game played between cars. But beyond the fun, kinship relationships, neighborhood rivalries, and social hierarchies were also being negotiated. Formal team sports are an outgrowth of this sort of casual play, and the larger the group, the larger the terrain.

FIGURE 1.1

North American Indians played a diverse set of games and sports. Lacrosse, a Native American invention originating in upstate New York, is still played today.

Source: Culin (1907).

And sometimes the terrain in sports gets very big indeed. Sometimes it is a proxy for war. Many anthropologists believe that sports are a kind of ritualized war, which is in itself a form of competition with winners and losers. I mentioned above the high stakes involved in pre-Columbian ball games. Aristotle referred to sports as an expression of aggression without the blood—or at least the amount of blood shed in warfare. Diverse contact sports involve aggression, and blood is shed by both the fans and the players (think of Manchester United’s matches). That is the nature of some sports: brute aggression and group solidarity.

Early on, some sense of what we would now call nationalism, with devotion to a particular team or competitor based on their geographic or ethnic origins, was introduced into sport. It is that nationalism or regionalism (Argentina versus Brazil, Oakland versus San Francisco) that leads to the roar of identification and glorification that goes up in any modern sporting arena. I marveled at the Cuban boxers and the Eastern European gymnasts—their dedication and the fanatical followings they acquired—during the heyday of the communist countries. Again at the 2014 Olympics in Sochi, we saw sport stand in for deadlier rivalries on the world stage. The ritual significance of the earliest games is surely alive in modern sport.

Such identity-based purposes for games have an old and rich history. In the Orkney Islands, off the northern tip of Scotland, the Kirkwall ba’ game is played in several iterations over the Christmas and New Year holiday, traditionally between the Uppies (the inhabitants of the upper part of the town) and the Doonies (those who live around the harbor). This is an exuberant and sometimes vicious free-for-all with few rules apart from getting the ball across the dividing line between the two parts of town, and the scrums can number up to 350 men (women and boys do not play in the main game, but they may have their own set-to). While Kirkwall ba’ goes back at least to the seventeenth century, it may be far older. The presence of similar games is attested to in many parts of the British Isles and America. If sport began as ritualized war, designed to bleed off aggression between natural rivals, games such as the Kirkwall ba’ game are the closest modern relative of that ancient sport.

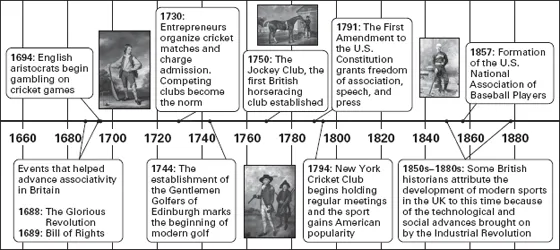

The cultural evolution of association eventually led to small groups coming together to form organizations (de Tocqueville 1848). This was most apparent starting in the 1850s in the United Kingdom. Clubs, an important feature of life in the Victorian era, were organizations for social interaction (Szymanski 2006). Modern sport is essentially secular and tied to records (Guttmann 1978). This timeline of sport reflects both aristocrats and commoners.

Associative sports in Britain and the United States paralleled the development of public societies, government bodies, and other social organizations. The formation of cricket, golf, and horse-racing clubs marked the beginnings of early sporting organizations that would one day become the modern franchises we now associate with games such as football, basketball, and baseball (Syzmanski 2006).

FIGURE 1.2

A timeline depicting how association—in this sense, the formation of sport specific clubs—led to the development of modern sports.

Source: Adapted from Szymanski (2006).

Cricket, a precursor of baseball that still has a fanatical following in England, Australia, India, and Pakistan, is a prime example of associative sport. Cricket clubs were common from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth; every English village once had a cricket club and could field a team. Horse-racing and jockey clubs, more popular with the upper classes, were also common during that period.

As Syzmanski (2006) points out, associations also developed elsewhere in Europe, such as France and Germany, and some were tied not only to games and sports but also to education and to the gymnasium as a place to express and develop athletic excellence.

THE ORIGINS OF SOME SPORTS

It is more difficult to find the exact origins of many sports played by individuals because leagues and chapters were not established for them in the same way they were for team sports. Boxing may have emerged as a sport in the Greek Olympics of 688 BC. It evolved into prizefights in sixteenth- to eighteenth-century England, eventually becoming the sport we know today. Cycling as a sport began in France shortly after the invention of the bicycle.

Golf appeared in many varieties throughout Europe in the Middle Ages, but it developed most thoroughly in Scotland. Gymnastics and acrobatics have evolved over seven thousand years in many places, both as forms of entertainment and for military training. Training centers for civilian gymnastics opened broadly in many places in Germany in the nineteenth century (Mandell 1999).

The origins of these sports are diverse. Baseball developed out of eighteenth-century folk games in England, and lacrosse is a modification of a game played by Eastern Woodland Native Americans and some Plains Indians tribes in Canada. Basketball did not evolve on its own, as many games probably did, but was invented in Massachusetts in 1891 by the physical-education teacher Dr. James Naismith, the son of two...