![]()

The Heritage

![]()

1.

Setting the Stage: Islam and Muslims

Who are the Muslims? Where are they to be found? How many are they? Many people assume that most Muslims are Arabs. In fact, Arabs make up only about one-fifth of the total world Muslim population.

Others, even if aware that the Middle East contains many inhabitants other than Arabs, are inclined to think that the Muslim world and the Middle East are roughly coterminous. It is true that the Middle Eastern population is about 90 percent Muslim, but all the Muslims of the Middle East still add up to a minority of the world’s Muslim population. Even when defining the Middle East broadly to embrace the entire Arab world from Morocco to the Arabian Peninsula plus Iran, Israel, and Turkey the Muslims thus included are only slightly more than one-third of the world’s Muslim population.

The largest Muslim state, Indonesia, is not in the Middle East. Indeed, the first four Muslim states in terms of population are all outside the Middle East—Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and (surprising to many) India with over 100 million Muslims.

There are approximately half again more Muslims in the states of the former Soviet Union than in all of the Fertile Crescent states (Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria), and the Muslims of Nigeria outnumber the Muslims of the entire Arabian Peninsula by roughly two to one.

The total world Muslim population is estimated to be slightly more than one billion. This gives a ratio of roughly six Muslims in the world for every ten Christians. There are slightly more Muslims than Catholics. Muslims outnumber all Protestants combined by almost three to one.1

Muslims are a close second to Christians (315 million as against 356 million) in the continent of Africa. They outnumber Hindus in all Asia (812 million versus 776 million) and are far ahead of the third largest group, the Buddhists (349 million). There are more than twice as many Muslims as all Christians throughout Asia.

Islam is, thus, by far the largest religious community in the Afro-Asian world with almost 400 million more than the Hindus, and outnumbering Christians by almost five million and Buddhists by a ratio of three to one.

In worldwide terms Muslims account for somewhat more than one-fourth of the total membership of the principal religions in terms of numbers of adherents (Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism).

Islam began in the Middle East, as did Judaism and Christianity. Unlike its two sister religions, however, Islam has never suffered a statistically significant loss of its followers in the land of its origin. At different times and in response to different challenges the center of gravity of Christianity and Judaism (in demographic and cultural terms, at least) moved from the Middle East to Europe and the lands of largely European settlement, i.e., roughly what is now loosely labeled the West. Islam, always a proselytizing religion like Christianity, also expanded, but never at the expense of its Middle Eastern core area.

This may partially explain why so many outsider observers associate Islam with the Middle East even though the region accounts for a minority of the world’s Muslims and has been in that minority status for centuries. Among Muslims, as well, there is a decided tendency to consider the Middle East both the homeland and the heartland of Dar al-Islam (the abode of Islam).

Many important aspects of Islam serve to remind Muslims of this special attachment to the Middle East. God chose to give what Muslims deem the final revelation in the Arabic language, and from the rise of Islam to this day Arabic has been the vehicle of Muslim ritual and theological communication. It is perhaps no exaggeration to say that Arabic is to Islam what Hebrew, Greek, and Latin all together are to Christianity.

Muslims everywhere face toward the Holy Ka‘ba in Mecca in prayer. Pilgrimage to Mecca—the Hajj—is a ritual obligation that all Muslims whose health and wealth permit are enjoined to fulfill at least once in a lifetime. The number of Muslims who have made that pilgrimage throughout the centuries is impressive. In recent years over two million Muslim pilgrims have come to Mecca each year during the pilgrimage season.2 Only slightly less holy in Muslim eyes is Madina, roughly 270 miles north of Mecca where Muhammad gathered his earliest converts and founded a religio-political community. It was also at Madina that the Prophet died in 632 C.E., and this city—the second holiest in Islam—served as the seat of the caliphate (the leadership of the Muslim community) in the crucial first few years of Islamic history after the death of Muhammad.

The third holiest city of Islam—Jerusalem—is also very much in the center of the Arab Middle East. It was from Jerusalem that the Prophet Muhammad, as related in the Qur’an, made his miraculous ascent to heaven. Jerusalem was also the first qibla (direction toward which Muslims are to face in prayer). Only a later Qur’anic revelation changed the qibla to Mecca.

Two other holy cities, especially venerated by the Shi‘i Muslims, are also located in the Middle East heartland. They are Najaf, where Ali, the fourth caliph and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, is believed to be buried, and Karbala, which witnessed the martyrdom of Ali’s son, Husayn (on the tenth day of the month of Muharram in 61 A.H. or 680 C.E., commemorated thereafter by Shi‘i Muslims as the principal day of mourning in the liturgical year). Both Najaf and Karbala are located in modern Iraq.

The formative years of what might be called political Islam are also solidly embedded in a Middle Eastern geographical context. As a result, many other Middle Eastern place names resonate with religio-cultural connotations to Muslims wherever they may be: Damascus, the capital of the first Muslim dynasty, the Umayyads (661–750), and Baghdad, the capital of the succeeding long-lived Abbasid dynasty (750–1258) evoke religio-political memories for Muslims much the way the names of Rome and Constantinople call forth the Christian religio-political heritage.

Also located in the Middle Eastern heartland are many of the later imperial and cultural capitals of Islam, including Cairo, founded as a new Islamic capital city in 969, Istanbul, wrested from the Byzantines in 1453 by the Ottomans and serving as their imperial capital until the end of the Ottoman Empire following the First World War, and Isfahan, the old Persian city that later became the resplendant capital of the Safavid Empire (1500–1736).

For all these reasons there is an understandable tendency among both Muslims and non-Muslims to emphasize the Middle Eastern dimension of Islam, past and present, and accordingly to give less attention to the majority of the world’s Muslims who live outside the Middle East.

Observers are also likely to attribute to Islam behavioral patterns that are more properly to be traced to the Middle Eastern cultural legacy. There is no easy answer to this problem of perception. The Middle Eastern matrix of Islam is a historical fact. Moreover, the area of the Middle East that provided the arena for the activities of the Prophet Muhammad and the first few generations of his followers continues to stand out in Muslim consciousness as a distinctive, if not, indeed, a holy land. At the same time, Muslims everywhere are aware that many mundane and unholy activities take place in the Middle East and have done so for centuries.

The prudent observer should seek a middle path in weighing the Middle Eastern role in Islam as a religion and as a culture. The Middle East and Middle Easterners are perhaps more important to an understanding of Islam than any comparable territory or similar number of people, but, for all that, the Middle East is home for only a minority of the world’s Muslims. Any effort to isolate the special Islamic element in shaping the political life of Muslims must give those peoples and regions beyond the Middle East due consideration.

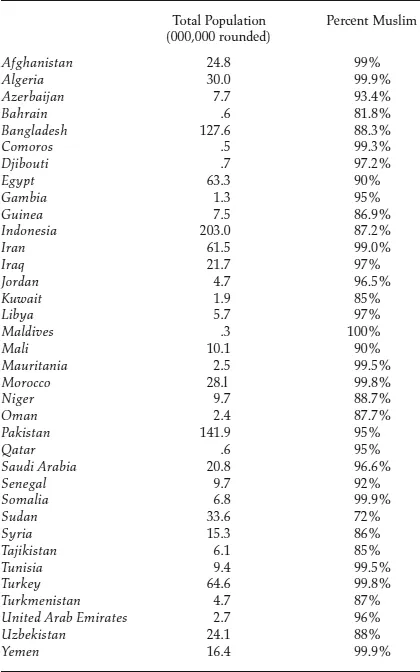

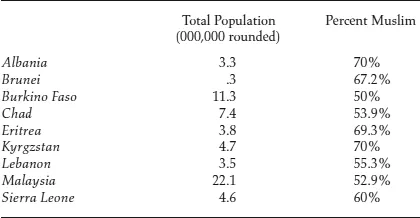

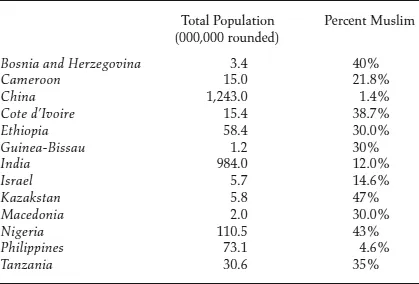

The different peoples making up Dar al-Islam can be classified according to a number of criteria. There are, for example, states with Muslim majorities as opposed to those states in which they are a minority (See tables 1.1–1.3).

Table 1.1 States in Which 75 Percent or More of the Population Are Muslims

Table 1.2 States with Muslim Majorities Ranging from 50 Percent to 75 Percent

Table 1.3 Selected States with Significant Muslim Minorities Either in Total Numbers or as a Percentage of the State’s Population

Even the tiny 2.4 percent in China amounts to 18 million Muslims. There are an estimated 105 million Muslims in India. A few midsized states, not listed, have Muslim minorities constituting a larger percentage of the total population than found in the Philippines, e.g., Ghana, 16.2 percent, Malawi, 16.2 percent, Mozambique, 13 percent, Yugoslavia, 19 percent, or even Singapore, with 15 percent. Information on the Philippines (4.6 percent or 3.3 million) was listed, because leaders of that tiny minority have adopted an adamant “Muslim nationalist” position.

Source: Britannica Book of the Year, 1999.

Muslims may also be divided according to cultural areas or regions with common mores and traditions in which such basic matters as language, gender roles, child rearing, cuisine, housing, play, and patterns of politesse bind people together and make them different from other peoples with other mores and traditions. A rough-and-ready breakdown of such separate Muslim cultural areas might be as follows:

The Arabian Peninsula

The Fertile Crescent

Anatolia and the neighboring areas of Turkic language and culture

The Iranian plateau, Afghanistan, and Persian speaking portions of former Soviet Central Asia

The Nile Valley (Egypt and Sudan)

Northwest Africa (the Maghrib)

West Africa

East Africa

Northwestern Indian subcontinent (largely now Pakistan)

Northeastern Indian subcontinent (largely now Bangladesh)

Central and Southern Indian subcontinent

The East Indies (Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei)

The old Muslim populations in Europe (Albania and Bosnian Muslims)

The new Muslims minorities in Europe (Arabs and Turks in Western and Central Europe)

Smaller minorities (e.g., the United States, Philippines, Latin America)

Yet another way of distinguishing the world’s Muslims is according to the different denominations of Islam. Just as Christianity can be divided into Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant plus several smaller sects Islam also has its divisions. They are, however, fewer than in Christianity and with sharply different proportions. The overwhelming majority are Sunni Muslims. Sunni is an Arabic word meaning custom or tradition. It is often translated into English as “orthodox,” which is an accurate enough description of the Sunni Muslim self-image. Muslims who are not Sunnis, however, do not accept that they are thus heterodox. Sunnis account for roughly 84 percent of the world’s Muslim population.

Virtually all of the remaining Muslim population is composed of the various Shi‘a groups constituting 16 percent of the total Muslim population.3 Shi‘a, another Arabic word, means partisan or follower, and it is used to designate those Muslims who believe that the religious leadership (imama, anglicized to imamate) rightly belonged to Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, and thereafter to his descendants. The Shi‘a can in turn be divided into three numerically disproportionate groups—Twelver, Sevener, and Zaydi Shi‘a, the great majority being Twelver Shi‘a. The number twelve indicates the count of imams, beginning with Ali and followed by his two sons, Hasan and Husayn, who were physically present in this world to lead the community before the last in the line (the twelfth) left the visible world and went into occultation (ghayba).

These Shi‘i imams are deemed to have been without sin and have a special relationship to God. Moreover, it is believed that the return of the occulted, or hidden, imam will signal the end of time and the consummation of the divine plan. This amounts to a striking similarity of Shi‘i Islam and Christianity as contrasted with Sunni Islam and Judaism. Shi‘ism and Christianity both posit a more imminent God in the form of an individual presence in this world, human but partaking of divinity (the imam or Christ). Judaism and Sunni Islam, by contrast, both stress a more transcendant God.

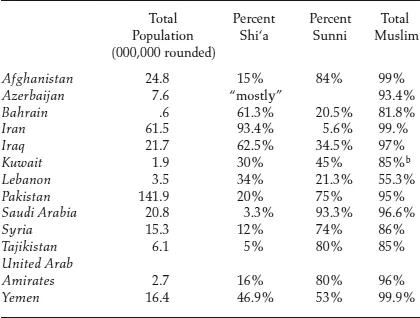

The Twelvers account for by far the majority of the world’s Shi‘a Muslims. They constitute the overwhelming majority in Iran, are also a majority (over 60 percent) in neighboring Iraq, in Bahrain and Azerbaijan, and are clearly the largest community in multiconfessional Lebanon. In other countries they have minority status. (See table 1.4).

Table 1.4 States with Significant Shi‘i Muslim Populationsa

Source: Britannica Book of the Year, 1999.

a Not a complete listing. Shi‘i minorities may well be underestimated in certain cases. The Lebanese figures are at best “guestimates.”

b Includes 10 percent “other Muslim.”

Another, much smaller, number of Shi‘is are customarily classified under the rubric of Seveners, for they believe that a different son of the sixth imam succeeded to the imamate. This son, Ismail, predeceased his father, but those who became the Sevener Shi‘is either believed that Ismail remained alive or that Ismail’s son should have succeeded to the imamate. Thus, the name Ismaili is still used to identity those Shi‘is of this persuasion. Much more could be said about the role of Sevener Shi‘is in Muslim history, just as minority or “extremist” groups often provoke the majority or “mainstream” bodies to more clearly define their positions. For present purposes it will suffice to record the following: the most important political challenge posed by the Sevener Shi‘i was that of the Fatimids in the tenth century C.E. They seized political control in the Maghrib, Egypt and geographical Syria, seriously threatening the Sunni Abbasid caliphate ruling in Baghdad.4

As Fatimid power waned, Sevener Shi‘ism took a radical turn, spawning the “Assassins,” from the Arabic word for hashish users, made famous in Western history by their confrontation with the Crusaders. The Bohra and Khoja Isma’ilis, the latter followers of the Agha Khan, are descendants of these radical Sevener Shi‘i groups. Most of these Ismailis are now Indian Muslims of quietist bourgeois orientation. They can perhaps be compared, in terms of this evolution, to today’s Quakers, Amish, and other Christian groups who evolved from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Anabaptists, Shakers, and others who were once quite revolutionary. Many Ismailis now live as important diaspora communities in East Africa and Britain.

Also evolving from Sevener Shi‘ism are the Druze, who typify the type of religious community that is nonproselytizing, has an esoteric doctrine, and has been able to keep its tight-knit communal nat...