eBook - ePub

Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk

Lu Xun

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 160 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk

Lu Xun

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

A collection of essays by Lu Xun, one of the most influential figures of modern Chinese literature. In this classic and beautiful collection, Lu Xun recounts the stories of his childhood and youth in Shaoxing, China. A revolutionary thinker and writer, and one of the architects of the May 4th Movement, his stories reveal the beauty, joy, and struggle of life in early twentieth-century China.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk de Lu Xun en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Literatura y Ensayos literarios. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

LiteraturaCategoría

Ensayos literarios■ Postscript

At the start of my third essay on The Twenty-Four Acts of Filial Piety, I said that the term Ma Huzi used in Peking to frighten children should be “Ma the Hun” because it referred to Ma Shumou, whom I took to be a Hun, I now find I was wrong. Hu was General Ma Shumou's first name. This appears in Notes for Idle Moments by Li Jiweng of the Tang Dynasty. The section entitled “Refuting the View That Ma Shumou Was a Hun” reads as follows:

“Common people frighten children by saying, ‘Ma Huzi is coming!’ Those not knowing the origin of this saying imagine Ma as a god with a big beard who is a harsh investigator of people's crimes; but this is wrong. There was a stern, cruel general of Sui called Ma Hu, to whom Emperor Yang Di entrusted the task of building the Grand Canal at Bianliang. So powerful was he that even children stood in awe of him and would frighten each other by saying, ‘Ma Huzi is coming!’ In their childish prattle the Hu changed into Hun.

This is just like the case of General Hao Pin of the prefecture of Jing in the reign of Emperor Xian Zong, who was so feared by the barbarians that they stopped their children from crying by scaring them with his name. Again, in the time of Emperor Wu Zong, village children would threaten each other ‘, Prefect Xue is coming!’ There are various similar instances, as is proved by the account in the Wei Records of Zhang Liao being invoked as a bogeyman.” (Author's note: Ma Hu's Temple is in Suiyang. Li Pi, Governor of Fufang, who was his descendant, had a new tablet erected and inscribed there.)

So, I, in my understanding, was just like “Those not knowing the origin of this saying” in the Tang Dynasty, and I truly deserved to be jeered at by someone a thousand years ago. All I can do is laugh wryly. I do not know whether this tablet is still at Ma Hu's Temple in Suiyang or whether the inscription has been kept in the local records or not. If they still exist, we should be able to see his real achievements, which would be the opposite of those described in the story Record of the Construction of the Canal.

Because I wanted to find a few illustration, Mr. Chang Weijun collected a wealth of material for me in Peking, among it a few books which I had never seen. These included Picture-Book of Two Hundred and Forty Filial Acts by Hu Wenbing of Suzhou, published in 1879, the fifth year of Guang Xu. The word “forty” was written 卌 and there was a note to the effect that this should be pronounced xi. Why he went to such trouble instead of simply writing “forty” passes my understanding. As to that story to which I objected about Guo Ju burying his child alive, he had already cut it a few years before I was born. The preface says:

“... The Twenty-Four Acts of Filial Piety brought out by the publishers is an excellent book, but its account of Guo Ju burying his son is not a good example to follow, according neither with reason nor human feeling.... I have rashly taken it upon myself to bring out a new edition, weeding out all those stories which aim at winning a name by exceeding proper limits, and choosing only which do not deviate from the rules of propriety and which can be taken as examples by all. These I have grouped into six categories.”

The courage of this old Mr. Hu from Suzhou is certainly admirable. But I think many people must have shared his views, from way back too, only probably lacked the courage to make bold cuts or commit their views to writing. Take for instance The Picture-Book of a Hundred Filial Acts published in 1872, the eleventh year of Tong Zhi, with a preface by Zheng Ji (alias Zheng Jichang) which says:

“... Now that morality is going to the dogs and the old customs are being undermined, forgetting that filial piety is human nature people regard it as something quite apart. They pick out stories of men of bygone days throwing themselves into furnaces or burying children alive and dub them as cruel and irrational, or accuse those who cut flesh from their things or disembowelled themselves of injuring the body given them by their parents. They do not realize that filial piety is a matter of feeling, not of outward forms. It has no fixed forms, no fixed observances. The filial piety of ancient times may not suit present needs; we today can hardly model ourselves on the ancients. For the time and place have changed, and different people will perform different deeds although all alike wish to be filial. Zi Xia said that a man should put his whole strength into serving his parents. So if people asked Confucius how to be filial his answer would vary according to different cases....”

From this it is clear that in the reign of Tong Zhi some people considered such acts as burying a child alive as “cruel and irrational.” As for this Mr. Zheng Ji's personal views, I am not too clear about them. He may have meant that we need not follow such old examples but at the same time need not consider them wrong.

The origin of this Picture-Book of a Hundred Filial Acts is rather unusual: it was the result of reading New Poems on a Hundred Beauties by a man called Yan from eastern Guangdong. Whereas Yan laid stress on female charm, the author laid stress on filial piety, showing splendid zeal in championing morality. However, though this book was complied by Yu Baozhen (alias Yu Lanpu) of Kuaiji, in other words, a man from my own district, I still have to say frankly that it is not up to much. For example, in a note to the story about Mulan joining the army in her father's place, he ascribed it to the “Sui Shi” (Sui Dynasty History). No book of this name exists. If he meant the Sui Shu (Records of Sui), that work has no reference to Mulan joining the army.

Still this book was reprinted in lithographic edition by a Shanghai publisher in 1920, the ninth year of the republic, under the amplified title Complete Edition of the Picture-Book of a Hundred Filial Acts by Men and Women. And on the first page, in small print, were the words: Good models for family education. There was also an additional preface by a certain Wang Ding (alias Wang Dacuo)of Suzhou, which started off with a lament similar to the views of Mr. Zheng Ji of the Tong Zhi reign:

“Ever since European influence spread east, scholars within the Four Seas have been advocating freedom and equality, so that morality has daily declined and men's hearts are becoming daily more depraved, unscrupulous and shameless, making them do all manner of evil, running risks and trusting to luck to get ahead. Few indeed are the men of integrity who have scruples and will not lower themselves.... I see that this world's irrational cruelty is well-nigh as bad as the heartlessness of Chen Shubao. If this tendency goes unchecked, what will our end be?...”

Chen Shubao may actually have been so stupid that he seemed completely “heartless,” but it is rather unfair to drag him in as an example of irrational cruelty, when such terms had been used by others to describe Guo Ju's burying his son and Li E throwing herself into a furnace.

In some ways, however, people's hearts do seem to be growing more depraved. Ever since the publication of Secrets Between Men and Women and New Treatise on Intercourse Between Men and Women, many books published in Shanghai use “men and women” in their titles. So now these words have been added even to the Picture-Book of a Hundred Filial Acts which was published to “rectify men's minds and improve their morals.” This is probably something never expected by Mr. Yu Baozhen of Kuaiji, who because of his dissatisfaction with the New Poems on a Hundred Beauties preached filial piety.

To depart suddenly from filial piety, “the foremost of all virtues,” to drag in “men and women” may seem rather frivolous if not depraved. Still, I would like to take this chance to say a few words on this subject. Of course, I shall try to be brief.

We Chinese, I dare say, even when it comes to “the foremost of all virtues, may sometimes start thinking of men and women too. The world is at peace, so idle people abound. Occasionally some “kill themselves for a noble cause” and may be too busy themselves to bother about other matters, but onlookers who remain alive can always carry out detailed researches. Official histories relate, and it is quite commonly known, that Cao E jumped into the river to look for her father, and after drowning herself still carried his corpse out. The problem is: How did she carry his corpse?

When I was small, I heard elders in my hometown explain it this way:

“... At first, the dead Cao E and her father's corpse floated up to the surface with her clasping him, face to face. But passers-by seeing this laughed and said: ‘Look, such a young girl with her arms round such an old man!’ Then the two corpses sank back into the water. After a little they floated up again, this time back to back.”

Fine! According to the records, “E was only fourteen.” But in this realm of propriety and righteousness, even for so young a dead filial daughter to float up from the water with her dead father is very, very hard.

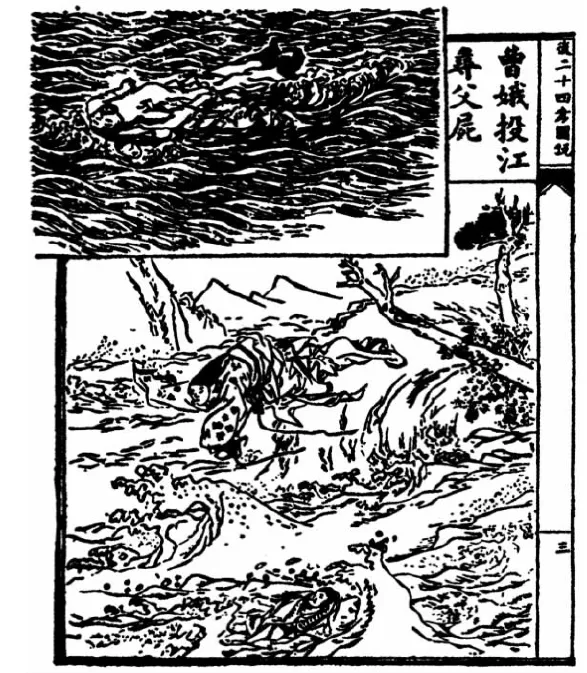

I looked up the Picture-Book of a Hundred Filial Acts and Picture-Book of Two Hundred and Forty Filial Acts. In both cases the artists were clever: they had only drawn Cao E weeping on the bank before jumping into the river. But the 1892 edition of The Picture-Book of Twenty-Four Filial Women illustrated by Wu Youru showed the scene of the two corpses floating up, and he had made them “back to back” as we see in the uppermost of the first illustration. I expect he had heard the same story that I did. Then there is the Supplementary Picture-Book of Twenty-Four Filial Acts also illustrated by Wu Youru, in which Cao E is again presented, this time in the act of plunging into the river, as we see in the lower of the first illustration.

A great many of the illustrated stories preaching filial piety which I have seen show filial sons through the ages up against brigands, tigers or hurricanes, and nine times out of ten their way of coping with the situation is “weeping” and “kowtowing.”

When will we stop “weeping” and “kowtowing” in China?

As far as draughtsmanship is concerned, I think the simplest and most classical style is that of the Japanese edition by Oda Umisen. Having already been incorporated into Paintings Collected by Dianshizhai, this has become a Chinese product and so is very easy to get hold of. Wu Youru's illustrations, being the most meticulous, are also the most engaging. But in point of fact he was not too well fitted to draw historical subjects. For he was so thoroughly imbued with what he had seen and heard in the course of his long residence in the International Settlement in Shanghai that what he really excelled at was contemporary scenes such as “A Fierce Bawd Abuses a Prostitute” or “A Hooligan Makes Advances to a Woman.” Such pictures are so full of vigour and life that they conjure up before us the International Settlement in Shanghai. However, Wu's influence was deplorable. You will find that in the illustrations of many recent novels or children's books all the women are drawn like prostitutes, all the children like young hooligans, and this is very largely the result of the artists seeing too many of his illustration.

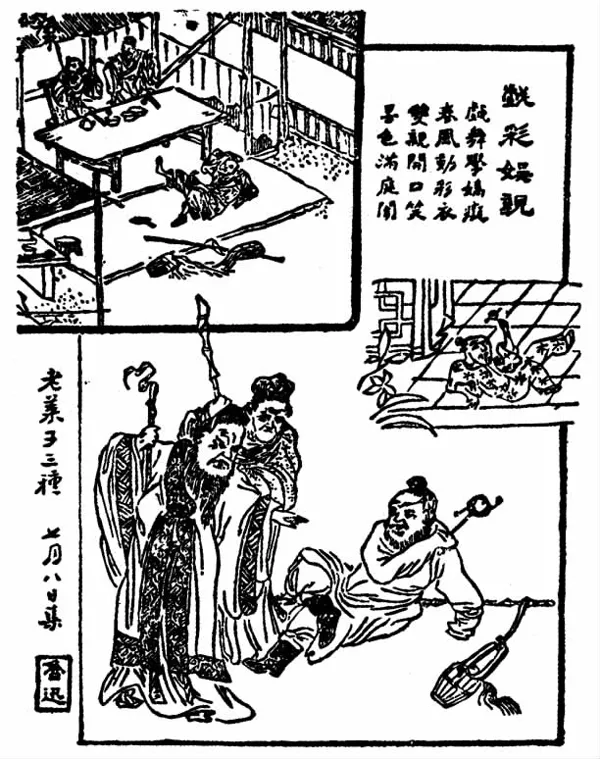

And stories about filial sons are even more difficult to illustrate, because most of them are so sad. Take for instance the story “Guo Ju Buries His Son.” No matter how, you can hardly make a picture that will induce children to lay themselves down eagerly in a pit. And the story “Tasting Faeces with an Anxious Heart” is hardly likely to make much appeal either. Again, in the tale about “Old Lai Zi Amuses His Parents,” although the verse appended to it says “the whole household was filled with joy,” the illustrations have very little in them to suggest a happy family atmosphere.

I have chosen three different examples for the second page of illustration. The scene at the top, from The Picture-Book of a Hundred Filial Acts, was drawn by He Yunti of Chencun. It shows Old Lai Zi pretending to fall while carrying water to the hall and crying like a baby on the ground, and also shows his parents laughing. The middle scene I copied myself from Pictures and Poems of Twenty-Four Filial Acts illustrated by Li Xitong of northern Zhili. It shows Old Lai Zi in multicoloured garments playing childish pranks in front of his parents. The rattle in his hand brings out the fact that he is pretending to be a baby. Probably, however, this Mr. Li felt that it looked too ridiculous for a fully grown old man to play such pranks, so he did his best to cut Old Lai Zi down in size, finally drawing a small child with a beard. Even so, it makes no appeal. As for the mistakes and gaps in the lines, they are neither the fault of the artist nor mine as copyist; one can only blame the engraver who in 1873, the twelfth year of Tong Zhi in the Qing Dynasty, worked in the Hongwentang Printing Shop on the west side of the southern end of Buzhengsi Street in the Province of Shandong. The bottom picture on this page was printed by the Shendushanfang Shop in 1922, the eleventh year of the republic, without giving the artist's name. The illustration contains two episodes—pretending to fall and playing pranks like a baby—but leaves out the “multicoloured garments.” Wu Youru's illustration also combines both episodes; and he has also left out the multicoloured garments, but although his Old Lai Zi is plumper and has his hair in two knots—he still looks unattractive.

It has been said that the difference between satire and invective is only paper-thin, and I think the same applies to winsomeness and mawkishness. A child playing pranks before its parents can be winsome, but if a grown man does this it cannot but be distasteful. A careless married couple displaying their mutual fondness in public can easily become embarrassing if they slightly overstep the bounds of what is amusing. It is no wonder, then, that no one could draw a good picture of Old Lai Zi playing pranks. I could not be comfortable, even for a day, living in a family such as these pictures show. Just think. How can this old gentleman in his seventies spend all his time playing hypocritically with a rattle?

People of the Han Dynasty liked to have paintings or carved reliefs of rulers of old, disciples of Confucius, eminent scholars and ladies and fili...