eBook - ePub

The Gaff Rig Handbook

History, Design, Techniques, Developments

John Leather

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 240 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Gaff Rig Handbook

History, Design, Techniques, Developments

John Leather

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This is the internationally regarded definitive handbook for anyone designing, building, rigging or sailing gaff

rigged craft. It provides a fascinating insight into the design, history,

techniques and developments of a rig which has evolved through the

centuries.

John Leather outlines the practical aspects of the masts,

spars, sails, running and standing rigging, and contrasts the

development of the gaff rig in Britain, America, Scandinavia and

France. 'Regarded internationally as the definitive book for anyone designing, building, rigging or sailing a gaff-rigged vessel.' Kelvin Hughes 'The book's longevity says it all.' Water Craft

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Gaff Rig Handbook un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Gaff Rig Handbook de John Leather en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Technology & Engineering y Engineering General. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

CHAPTER ONE

MASTS AND SPARS

THE DIAMETER OF A MAST is dependent on its height and the type of rig. Lower masts for gaff rig should be of parallel diameter from deck to hounds. Above the hounds the masthead may taper according to the pull imposed upon it by the angle of the gaff, arrangement of halliards, and whether a topsail or topmast is carried. The average proportion of lower mast diameter to height (h) between deck to hounds for English cruising yachts up to 50 feet length is ·024h. An old general rule for lower mast diameter was ⅞in for every foot of beam; another was 7/32in for every foot of length from deck to head of mast. Masts are usually stepped with a rake varying with rig and individual craft, to obtain optimum performance. For craft of 50 feet length and above the usual rake per foot of height for lower masts is ¼in for cutters and sloops, ⅜in for ketches and ½in for schooners. Two-masted craft usually have the forward mast at a greater rake than the after. This is most pronounced in schooners. Cutters and sloops may be greatly affected in balance by mast rake and their masts are often fitted at right angles to the waterline.

Gaff rig masts may be solid or hollow timber, or aluminium. Steel masts and booms were used in the large yachts of the past but this need not now be considered. Solid masts may be shaped from a tree in the round, cut from a long baulk of timber, or built up from pieces of timber. A mast shaped from a tree is usually the cheapest for small craft. Typically, a straight black spruce or fir tree is selected, Norway spruce being a favourite.

Both ends of the tree should be examined to locate the heart which should be as nearly as possible in the centre of the tree at each end. Generally trees of this type have no internal faults, but this can be verified by listening with an ear close to one end of the tree while the other is tapped. The sound should carry with clarity in a spar of considerable length. The tree should be of slightly larger diameter than the finished mast size and when the bark and sapwood are removed it should approximate to the finished diameter.

When planed and sandpapered to size it should be treated immediately with a liberal mixture of one part boiled linseed oil with two parts of paraffin (kerosene), and afterwards stood on end to drain moisture to its heel. Due to greater shrinkage of the outer wood fibres, longitudinal shakes and splits will appear in the surface but provided the linseed oil/paraffin mixture is applied for some time, these should not become serious and are not a weakness unless of great depth. However, there should be no shakes or flaws across the grain and any knots should be small and firm. Longitudinal shakes should afterwards be filled with a soft mastic stopping which will readily squeeze out when the timber swells. Large knots or flaws should be particularly avoided around the mast wedging position at deck, at the hounds, and at the halliard attachments. It is customary for the butt of the tree to be used for the head of a grown lower mast. Grown masts were widely used in small craft where shrouds were not fitted, particularly in Holland and North America. These were fitted with the butt at the keel to retain the natural resilience of the tree as a mast, helping it to stand without shrouds.

Oregon pine is the most suitable timber for solid spars cut from baulks, being light and extremely tough. Pitch pine is also strong but much heavier and does not have such straight grain as Oregon. Spruce is a stronger timber than either but is difficult to obtain in length and can be badly chafed by gaff jaws. Red, yellow or white pine are also used, if obtainable.

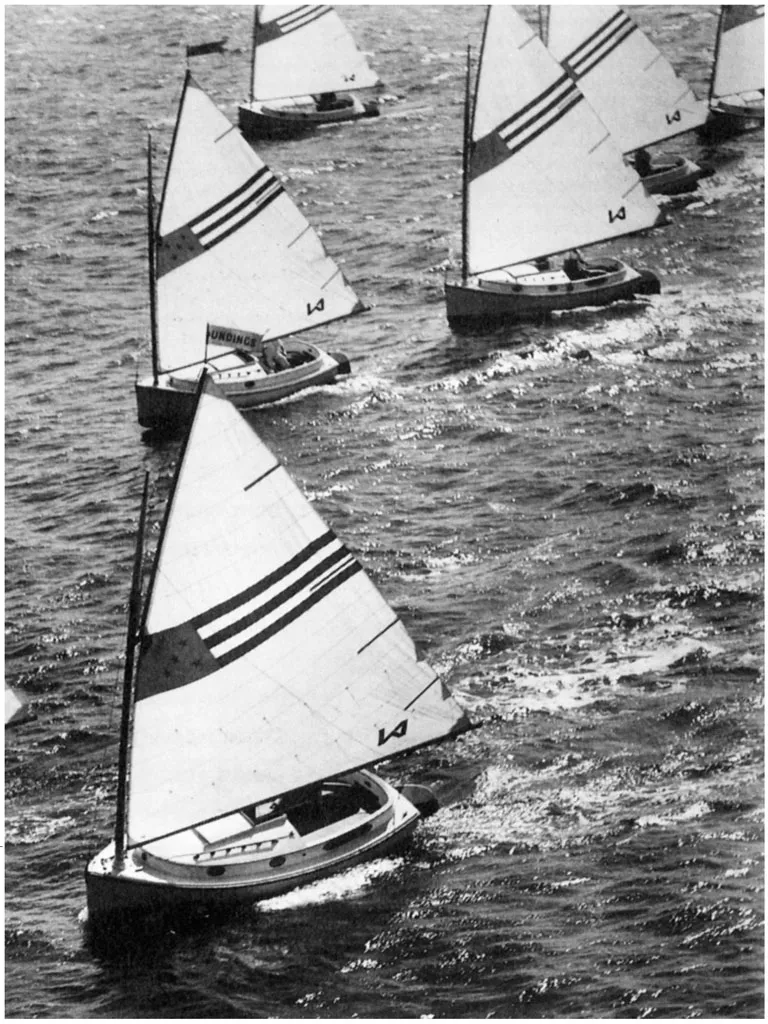

Many American catboats now have glass reinforced plastic hulls, aluminium alloy masts and spars and a Dacron sail. Fleet racing is keen in some parts of New England.

If the mast is large and long it will nowadays almost certainly have to be built from two or more pieces, scarphed and glued together with the scarphs carefully placed clear of deck, hounds, gaff jaws, etc; and the grain selected to avoid distortion of the completed mast.

Hollow wooden masts have been built since the mid-19th century but are now rarely used in gaff rigged yachts, though they saved much weight aloft in large yachts and are more rigid than solid masts. They are expensive and have to be made solid in way of the step, the deck, hounds, gaff jaws and mastbands or halliard bolts. Hollow wooden top-masts were sometimes fitted on the top of solid wooden lower masts, socketed into a special steel head fitting.

Aluminium alloy masts have been little used, as yet, with gaff rig. Some American glass reinforced plastic catboats have them and should provide a good test from the lack of staying and great twist imposed on the mast by cat rig. The principal disadvantage is that the gaff has to work up the mast in the sail track groove on a small swivel fitting which must withstand great strain and is liable to fatigue and break. Gaff jaws should not be used as they’ would quickly chafe the alloy and eventually cause mast failure.

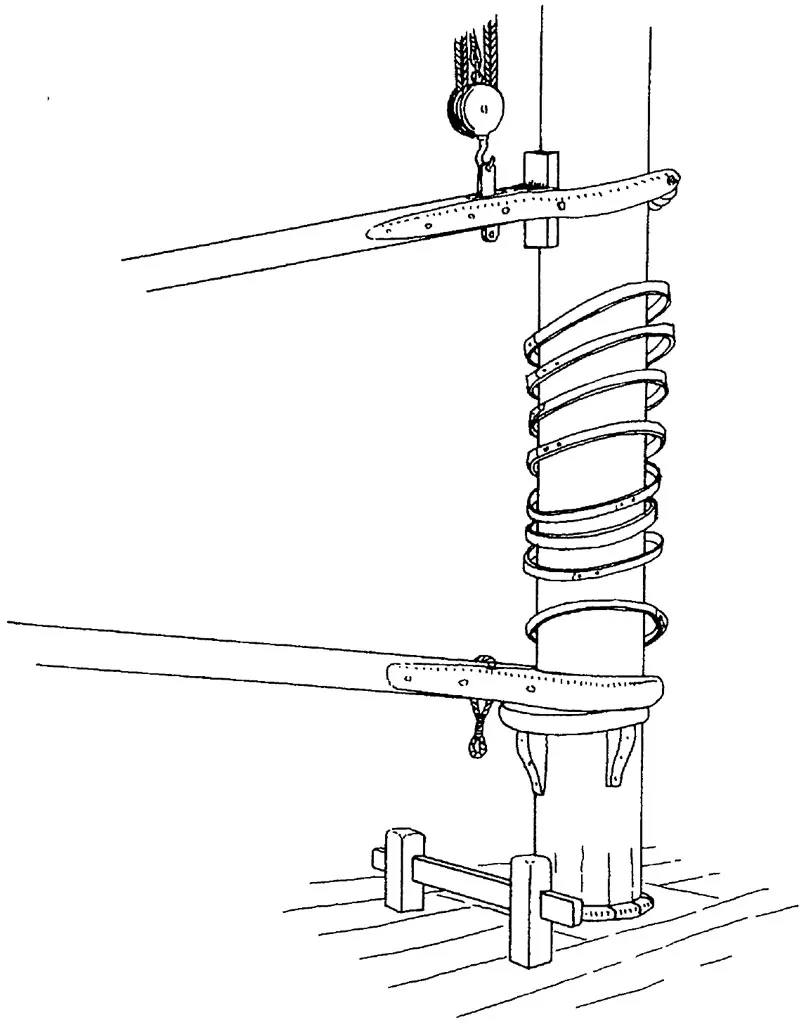

Masts may be stepped through the deck onto a chock on the keel or floors, or in a tabernacle on deck. Stepping on the keel or floors is traditional from the days when few craft, except racing yachts, had their masts removed for long periods. This method can place great strain on the garboards and adjacent structure when the craft is driven hard, and may cause leaks. Masts stepped thus are stiffer than those stepped on deck. The mast heel is shouldered down to a tongue which fits into a similarly sized slot in the chock, holding the mast from turning. Traditionally, a silver coin should be placed in the step, under the mast, for good luck. Masts cut from the baulk are usually left octagonal in shape in way of the deck to facilitate the fittin g of hardwood mast wedges at the deck chock, known as partners. If the mast is round throughout, shaped wedges have to be used, which are more awkward to fit and keep tight. When the mast is stepped and set up a canvas or Terylene mast coat is fitted snugly around it to cover the wedging and prevent water getting below. This is shaped as a flared skirt, is tightly laced around the mast with small cord, and its lower edges are turned over and tacked under a circular wood or metal ring which is screwed to the deck, making a watertight seal. In large craft the mast wedges are usually carefully caulked and payed or stopped over to make them tight. A mast coat is not then required.

Masts stepped on deck in a correctly designed tabernacle supported by a compression pillar do not cause bottom or deck leaks, provided the deck is suitably reinforced. They are more easily stepped and unstepped and may be lowered, in sheltered waters, for attention to rigging or passing bridges. However, deck stepped masts must be of greater diameter than those stepped through the deck, approximating to a 25 per cent increase in weight, and must be more completely stayed if acceptable lightness is desired. Wooden tabernacles are often fitted in traditional craft, but galvanised steel is superior in strength, lightness, ease of construction and neatness. The boom gooseneck and pinrails set well out from the mast may be incorporated in steel tabernacles.

MAST IRONWORK The boom gooseneck connects the boom to the mast. The conventional pattern has a single band, in two pieces, cramped together around the mast by two bolts and has a swivelling gooseneck on the after side and metal belaying pins on each side. This is an inefficient fitting as the band has to be cramped so tightly to hold it in place on the mast that the wood fibres are crushed, usually admitting water and causing rot. Also, the gooseneck often has a spike to drive into the boom-end instead of a ferrule or cup end, with long arms which can be fastened through the boom. The belaying pins are too close to the mast causing halliards to bear on the mast hoops and be too close together when belayed.

Figure 1. Boom horns

An improved fitting has two mastbands cramped as described, with the gooseneck sliding vertically on a rod between them. This distributes the strain evenly on the mast, increases the factional area of the mastbands and reduces the crushing. Screw or bolt fastenings are sometimes fitted in mastbands to keep them in place but this weakens the mast and all mastbands should be a driving fit or rely on an adequate area of friction, if cramped. The sliding gooseneck enables a tack tackle to set the luff taut and relieves wringing strains on the mastbands.

Figure 2. Simple iron gooseneck

Traditionally rigged craft have a pair of wooden horns fitted to the forward end of the boom (figure 1), lodging on a semi-circular wood mast collar supported by wood thumbs. The horns are covered with leather or hide on the inner faces, against chafe, and the mast should be lightly greased. In large craft a parrel line with lignum vitae balls secures the ends of the horns around the mast. This arrangement can be very noisy at night or in a seaway.

When a tabernacle is fitted it is usual to fit the gooseneck on its after side, particularly with lo...