![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Safari Tourism, Pastoralism, and Land Rights in Tanzania

On August 9, 2012, Avaaz.org, a self-described “global web movement” bringing “people-powered politics to decision-making everywhere,” organized an online petition titled “Stop the Serengeti Sell-Off.” The appeal highlighted the injustice of wealthy trophy hunters buying an area adjacent to Serengeti National Park for use as their own personal playground. The statement read: “At any moment, a big-game hunting corporation could sign a deal which would force up to 48,000 members of Africa’s famous Maasai tribe from their land to make way for wealthy Middle Eastern kings and princes to hunt lions and leopards.”1 Avaaz was referring to the Ortello Business Corporation (OBC), a hunting company established by businessman and member of the Dubai royal family Mohammed Abdulrahim al-Ali, and the Tanzanian government’s proposed plan to create a new protected area for trophy hunting, which would dispossess the Maasai people of over 37 percent of their land.2

Within twenty-four hours, over 400,000 people had signed the Avaaz petition, and after one week there were over 850,000 signatures. Together with local direct action including over 1,500 women turning in their CCM cards, the campaign seemed to work temporarily, putting pressure on the Tanzanian government to listen to the concerns of Maasai activists who claimed it was taking their land simply to appease the interests of powerful foreign investors. The reprieve was short-lived, as less than a year later, in April 2013, the government declared a new protected area that would split the Maasai people’s land, creating a 1,500-square-kilometer protected area for hunting and leaving the Maasai pastoralists with the remaining 2,500 square kilometers. Local leaders and activists protested the action, calling on the president to intervene. The government eventually relented and called for a process to address conservation and tourism in Loliondo.

This remote part of Tanzania was quickly becoming a laboratory for how conservation and tourism were to be managed within a neoliberal context. Efforts to convert Maasai village land into a conservation area in Loliondo were not new. On the eastern edge of Serengeti National Park, conservationists had long wished to resettle the residents, move the villages and incorporate the area into the park. But Maasai leaders had repeatedly resisted efforts to do so, in the process organizing not only a regional social movement but also a new political understanding of the state, international conservation, and what it meant to be a Maasai living in Loliondo. The persistent political resistance shown by Loliondo residents is a direct effect of this legacy. Whether the increased global attention will mark a turn for Maasai activists fighting against this “land grab” is still uncertain. The fact that the remote Maasai area of Loliondo was now a critical site in a global struggle for the future meanings of conservation, pastoralism, and communal land rights was, however, coming clearly into view.

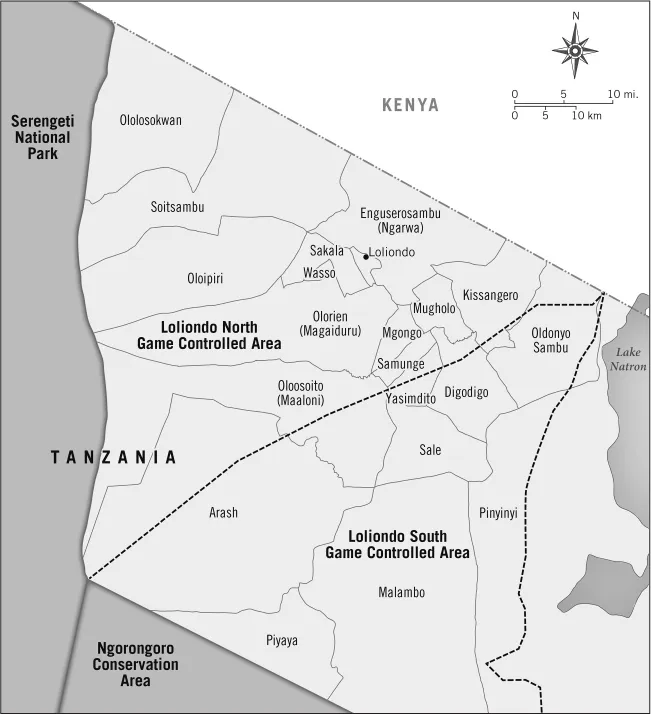

In 1992 the Tanzanian government had controversially granted the OBC exclusive hunting rights to Loliondo division, including the area made up of six villages that share a border with Serengeti National Park (map 1).3 The OBC’s continued presence in Loliondo over the past twenty years and its substantial influence with government officials have been a significant story line for critics of neoliberal globalization in Tanzania. Local journalists named the OBC’s unparalleled influence over government officials “Loliondogate.”4 Examples were cited in the press that included the construction of a private international airstrip in the remote location, lax oversight of hunting quotas, state police working as private security whenever the OBC is hunting in the area, and allegations of illegal live animal capture and transport to Dubai.5 Perhaps the most telling illustration of what journalists called “the privatization of Tanzania” was the OBC’s supposed “hijacking” of the country’s telecommunications system. When a cell phone is turned on near the OBC hunting camp, a message from the Abu Dhabi–based telecommunications corporation Etisalat greets you, “Welcome to the United Arab Emirates.”6

National and international media exploited the ethnic and religious background of the OBC directors, commonly referring to them as “the Arabs.”7 Daily papers suggested that their extreme wealth and opulence distinguished their transnational political power and enabled a callous lack of ethics. As the sole leaseholder for both of Loliondo’s designated hunting areas, the company garnered similar privileges granted to other foreign investors. The OBC was one of sixty registered companies, mostly foreign owned, that were granted a concession to one of the country’s 140 designated hunting areas by Tanzania’s Wildlife Division. While some of those hunting blocks, as they are called, are in game reserves with no permanent populations, the majority of hunting concessions in Tanzania overlap with established village land in either game-controlled areas or designated open areas (see chapter 3).

Between 1992 and 2009, local Maasai communities protested the OBC’s rights to hunt on their lands (see chapter 4). But despite media representations that depicted the OBC as the worst of the worst, many Maasai in Loliondo had come to see the OBC as a marginally better option than other hunting investors with their own reputations as entitled foreigners and for harassing local communities. As long as the OBC’s activities did not interfere with the Maasai pastoralist land-use system that depended on the same designated hunting area for dry-season grazing, they were generally tolerated. However, the fear that the OBC could wield extraordinary influence with the government if it chose to do so was substantiated on July 4, 2009. On that day Tanzanian police, using OBC vehicles, evicted thousands of Maasai people and tens of thousands of livestock from village land. The evictions were justified in the name of protecting the environment and maintaining the OBC’s state-sanctioned right to hunt in the area.8

MAP 1. Loliondo Division villages and overlapping game controlled areas where safari trophy hunting is permitted. XNR Productions.

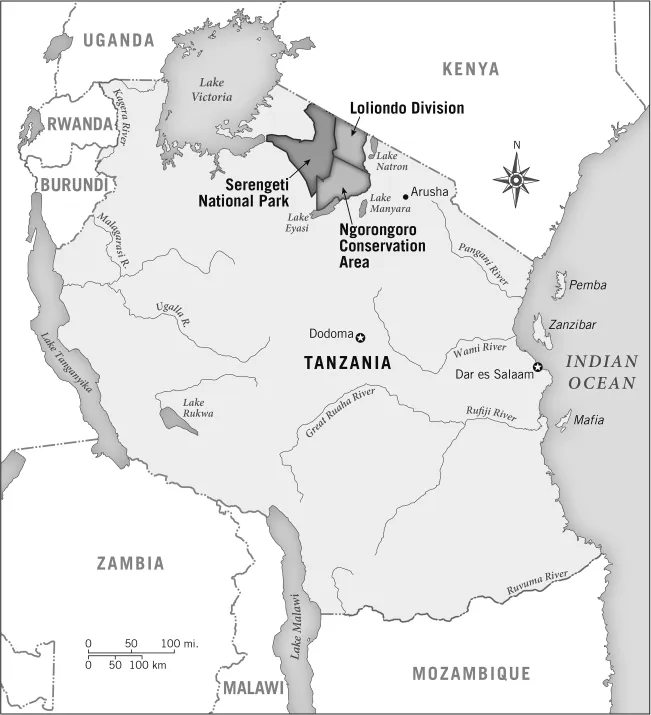

The Avaaz campaign came two years after the evictions, on the heels of the government-proposed solution to the conflict. A new protected area put forward by state wildlife authorities and district officials would permanently create a new space for conservation and big-game trophy hunting, essentially expanding the boundaries of Serengeti National Park (map 2). If successful, the state plan would build on past efforts to separate important wildlife habitat from populated village areas.9 According to officials, this was necessary to prevent future conflicts between “people and nature” in Loliondo. The rub was that the Maasai would lose 1,500 out of 4,000 square kilometers of communal grazing land that until then had been shared by wildlife and livestock. This was the worst possible outcome for the Maasai living in Loliondo, who had already surrendered much land, first when colonial powers placed the international boundary dividing Kenya and Tanzania through the middle of Maasai land and communities and then with the creation of Serengeti National Park and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in 1959.10

MAP 2. Ngorongoro Conservation Area and Loliondo Division in northeast Tanzania. XNR Productions.

Tourism, Neoliberalism, and Conservation in Loliondo

I was drawn to Loliondo in the early 1990s to study the relationship between Maasai livelihoods, conservation, and tourism. I came to appreciate how the history of land dispossession in the name of conservation, first by colonial authorities and then by the newly independent national government of Tanzania, had led many Maasai leaders and residents to embrace the promises of neoliberal political and economic reforms as a way to gain recognition for long sought-after land and human rights. Neoliberalization is a term used by geographers and other scholars to describe the set of policies and discourses that promote economic liberalization as a solution to global poverty and underdevelopment. Neoliberalism generally entails promoting free trade, privatization, deregulation, and opening new markets. Invoking neoliberalization as a theory, as well as a set of policy reforms, its advocates call for increasing the role of the private sector and limiting the role of the state to create investment and economic growth.11 Like most people and social groups in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the Maasai were thrown into the new political economic context of neoliberalism that came to dominate the world capitalist system in the mid-1980s and early 1990s.

Throughout the colonial period (1891–1961) and under the socialist developmental state (1961–85), the Maasai had consistently struggled against the government to defend pastoralist livelihoods and protect their land rights. The pressure to take Maasai land for wildlife conservation and large-scale agriculture was supported by a developmental ideology that saw pastoralism as a pre-modern social and economic system. Ideas for efficient and market-oriented range management based on private-property rights, popularized by ecologist Garret Hardin’s (1968) “Tragedy of the Commons” thesis, gave government officials and development experts the conviction they needed to justify massive interventions in pastoralist communities.

Market-oriented reforms arrived in Tanzania in the late 1980s at the same time that a crisis occurred in the “fortress conservation” model of wildlife protection, which called for the separation of people and wildlife (see chapter 3).12 Despite Tanzania’s extraordinary commitment to wildlife conservation, which entailed dedicating close to 35 percent of its land to protected status, the 1980s saw the rapid conversion of land bordering parks from rangelands to farmlands. The same period also saw an unprecedented rise in poaching activities within core-protected areas.13 A lack of resources, as well as hostile relations with bordering communities, put pressure on the conservation community of donors, NGOs, scientists, and state agencies to reimagine conservation by including a role for rural communities. Range ecologists at this time began to push back against Hardin’s thesis, arguing that pastoralism was in fact a highly productive system of land use that was more compatible with wildlife conservation than other rural production systems.14 Presented with opportunities to commoditize their lands for tourism, the Maasai actively adopted market-based community conservation arrangements. The promise of devolved rights to land and natural resources led many Maasai, searching for a tactical advantage in their struggle for land rights, to embrace many of the neoliberal ideas and ideologies that underpinned these projects. Seeing possible benefits such as a path to securing long-term property rights, Maasai leaders in Loliondo often became vocal supporters of policies that enabled direct foreign investment for tourism on village lands. At the same time, they opposed the state’s signature effort to manage tourism investment on village lands, the Wildlife Management Area (WMA) policy.

The recent evictions to create a lucrative hunting reserve and another controversial land deal in Loliondo to establish a private nature refuge expose the contingent practices through which the meanings of neoliberalism are produced. The Maasai in Loliondo have learned that trying to harness capitalism’s power to make claims for collective rights is a politically fraught undertaking. Neoliberalism provided new opportunities for both Tanzanians and foreigners to exploit their land and labor. A market approach to development also meant fewer state resources devoted to public services and basic state functions. How Tanzanians view neoliberal reforms depends largely on their identities and where they are situated within the nation-state. The Maasai people in Loliondo had rarely enjoyed the benefits and protections of the Tanzanian state. Because of this marginalized position, they often viewed neoliberal reforms differently than did many other Tanzanians. Informed by this history of state-society relationships, Maasai leaders have attempted to use their ability to negotiate directly with foreign investors, participating in commoditizing their landscapes, to create openings that they believe will help them realize the level of autonomous development for which they have long strived. Such independence or freedom from the state is often seen as a key aspect of neoliberal reforms. For many Maasai people in Loliondo, pursuing economic and political freedom turned on their ability to advance their status within the nation-state. I argue in this book that the Maasai have attempted to achieve these new forms of recognition by reimaging the village as a legitimate site of community belonging and rights and representing this image of the village to different audiences including tourism investors, state officials, and their fellow Maasai citizens. As I describe in the following chapters, this process has opened up political spaces as well as presented challenges.

Safari Tourism as a Site of Meaning and Profit

This book is an ethnographic study that examines how tourism investment in the Loliondo area of northern Tanzania remakes the ideas and meanings of economic markets, land rights, and political struggle. I consider three tourism arrangements in Loliondo: village-based tourism joint ventures in which foreign-owned ecotourism companies lease access to land from Maasai villages; a “private nature refuge” established by Thomson Safaris, a U.S.-owned tourism company that purchased 12,617 acres of village land in 2006; and a government hunting concession on village land managed by the OBC.15 I examine these projects to explain how state authority depends on articulating national agendas with the interests of private foreign investors (chapter 4); how the context of neoliberal development remakes social and spatial relationships, animating a new cultural politics of ethnic difference (chapter 5); and why Maasai activists have embraced some forms of investment as a way to assert their rights and defend their lands (chapter 6).

I contend that the context of neoliberalism has reshaped the meanings and values of Maasai landscapes and communities. This reshaping has altered the political tactics available to marginalized social groups like the Maasai. I argue neither for nor against the fairness of markets. Instead, I attempt to show that communities like the Maasai in Loliondo have little choice but to work within the discursive context of neoliberalism and attempt to use the techniques afforded by markets, such as contracts with investo...