![]()

ONE

The Judges and Cases

Most scholarship pertaining to the courts of appeals is limited to attempts to explain the ultimate decisions of the courts. Much less is known about the processes used by the courts to reach those decisions. This book fills in many of the gaps concerning how the courts of appeals operate on a-day-to day basis, drawing heavily on an extensive set of interviews we conducted with judges from every circuit. Before taking up the details of the way the courts operate, this chapter first turns a spotlight on the central actors on the courts of appeals, the judges. Appellate court judges’ decisions often represent the last word on many of the important legal questions of our time—but no one knows who they are. This chapter, then, constructs a portrait of appellate court judges, noting how the changing partisan balance on the courts has reflected trends in partisan control of the presidency, and the increasing gender and racial diversification of the appellate judiciary.

The Judges

Judges on the U.S. courts of appeals are among the most powerful people in American politics. As authors of the final decisions on important social and legal questions affecting large constituencies, they occupy a position quite different from that of many other key players in American politics, including governors, senators, and big-city mayors, all of whom are public personages living in the public spotlight.

However, this is not the fate of even the most influential or powerful of the judges on the courts of appeals. One of the most well-respected judges in the country, one who in addition to taking a leadership role on one of the busiest circuits in the country has written more than a dozen influential books on law, after noting this treatment of many of the celebrities in American politics had this to say about the reception of judges:

I can be holding a hearing in the morning on the interpretation of some new federal law, knowing that our decision is going to make new law that will affect millions of people, and it is easy to start thinking, hey, the three of us—we are pretty important people. Then after the hearing we walk out of the courthouse together and walk two or three blocks down a busy street to a popular restaurant for lunch, passing several hundred people on the sidewalks along the way, and not a single person—not even the waitress who takes our three credit cards to pay our lunch bill—recognizes us or pays any attention to us. It reminds me that regardless of how important I think my job is, the fact is that probably no one but a dozen or so lawyers in this town have any idea about who I am.

As this anecdote suggests, courts of appeals judges often go unnoticed even though their decisions affect millions of people.

Our goal in this chapter is twofold. First, we seek to describe who these mysterious key figures in American politics are. Second, we explain and analyze the structure and procedures of the courts of appeals. Both goals incorporate the perspectives of the judges along with empirical data. We begin our discussion with the process of selecting courts of appeals judges.

THE SELECTION OF JUDGES

The formal process for selecting judges on the courts of appeals is straightforward. Nominees are selected at the discretion of the president and take office if confirmed by a majority vote in the U.S. Senate. Once appointed, judges serve during “good behavior,” which effectively means they remain in office until they voluntarily retire or die.1

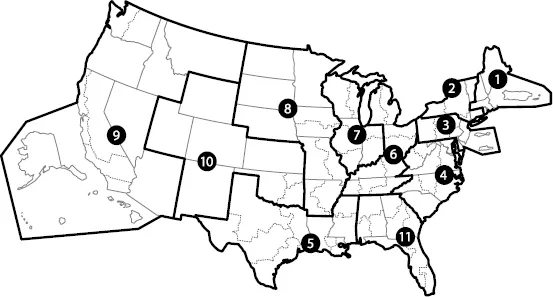

This seemingly straightforward practice is complicated by the political geography of the courts of appeals. As can be seen in the map of the circuits in figure 1, each circuit encompasses multiple states, but each state lies wholly within a single circuit. Consequently, each seat on the circuit is filled by a nominee from a particular state located within that circuit, and as a result, each U.S. senator is typically more concerned with nominees from her state than with those from other states (Steigerwalt 2010). In practice, the selection of an appeals court judge is a political process that involves negotiations between the White House and home state senators. Under the informal but strong norm of “senatorial courtesy,” a president is expected to confer with any senators of his party who are in the home state of the prospective nominee before the nomination is formally announced.2 Such home state senators can effectively veto the president’s choice if they are sufficiently opposed to the nominee, and on occasion the home state senator may convince the president to abandon his preferred nominee in favor of the senator’s choice. However, most nominations for the courts of appeals result from informal negotiations and bargaining between the president and the home state senators. Presidents usually have the upper hand in such negotiations, but the relative influence of the president and home state senators varies considerably from case to case, depending on the priorities, power, and policies of the relevant policymakers, including the president, the home state senators, the Senate majority leader, and the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee (see Binder and Maltzman 2009; Goldman 1997; Howard 1981; Songer, Sheehan, and Haire 2000; Steigerwalt 2010).

FIGURE 1. Circuit boundaries of the U.S. Courts of Appeals

Note: numbers indicate circuits. Source: www.uscourts.gov.

The politicization of the confirmation process has resulted in significant delays, as well as an increase in the number of rejected nominations, leading to a vacancy problem on the courts of appeals (Binder and Maltzman 2009). As an illustration of the vacancy problem, while there are 167 authorized courts of appeals judgeships, every year for the past twenty years between eleven and twenty-three of the positions have gone unfilled.

Of course, the vacancy problem is offset in part by the increased number of judges (from fifty-six in 1990 to 103 by 2007) who have taken “senior status” but are still participating in cases (we discuss the implications of this, as well as the use of designated judges, in chapter 2).3 Judge P explained that judges can remain on active status as long as they want (or until they die). Alternatively, a judge may voluntarily elect to take senior status at age sixty-five if he or she has at least fifteen years of service—but moving into senior status is not automatic. More precisely, Judge Q explained that eligibility for senior status is governed by the “rule of 80.” If a judge is at least sixty-five years old, has served for at least ten years, and his age plus years of service as an appeals court judge equals eighty, he is eligible to take senior status (see also Block 2007). As Judge E pointed out, judges on senior status may be as active or as inactive as they like; they may continue to hear a regular load of cases or they may sit for a reduced caseload. But, as Judge P pointed out, the general rule of thumb is that judges on senior status work half-time—that is, they hear half the number of cases heard by a judge on active status—and they are assisted by two law clerks and one secretary, rather than by the full-time judge’s allotment of four clerks, a secretary, and an administrative assistant. Judges on senior status receive full salary but generally may not participate when the circuit sits en banc to resolve a conflict in circuit law.4 According to our interviews, judges on senior status are also somewhat isolated from the administrative proceedings of the circuit and are usually not involved in the screening of cases.

PARTISANSHIP

Having described the appointment process, we now turn to a quick portrait of the types of people currently serving on the courts of appeals.5 The selection of appeals court judges is a partisan process, with more than 90 percent of the judges representing the party of the president who appointed them. Thus, the partisan balance on the court has largely followed the electoral successes of each president. The proportion of appeals court judges appointed by a Democratic president has ranged from slightly over 20 percent in the early 1930s to over 80 percent at the end of the Truman administration (Songer, Sheehan, and Haire 2000, 30). Party control of the courts of appeals has split nearly evenly in the twenty-first century.

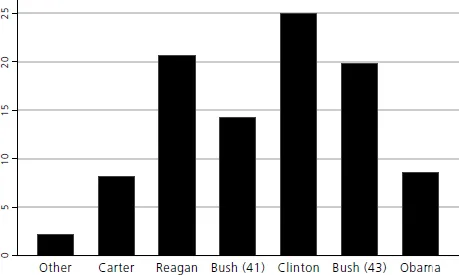

Turning our attention to the specific presidents who appointed the judges serving between 2000 and 2011, we see from figure 2 that four presidents, Reagan, Clinton, and the two presidents Bush, accounted for most of those who have served recently. However, president Obama had appointed twenty judges by the end of September 2011,6 and during his second term it is likely that the total number of judges appointed by Obama will eventually pass the appointment numbers of some of the other presidents reported in figure 2. Fewer than 10 percent of those serving in this century were appointed by President Carter, and almost no one remains who was appointed by a president before Carter.

FIGURE 2. Judges sitting on U.S. Courts of Appeals in 2000–2011 (N = 229) by appointing president (percent)

The relative influence of the most recent former presidents on the U.S. courts of appeals primarily reflects the lengths of presidential terms (the three presidents with the most appointees served two terms) and recency. However, the numbers also reflect a decreasing trend in the rate at which presidents appoint judges to the intermediate federal appellate courts. In a four-year term, Carter appointed fifty-six judges. By comparison, Reagan and George H. W. Bush appointed judges at relatively similarly rates to one another, but much lower than Carter’s (Reagan appointed eighty-three judges in two terms, an average of forty-one and one-half per term, and Bush appointed forty-two judges in his single four-year term). After that we see a precipitous drop, as Clinton and George W. Bush each appointed thirty-three judges, while Obama appointed thirty in his first term.

Part of this steep drop surely is due to the increasing delays in the confirmation process (see Binder and Maltzman 2009). However, part of the delay reflects the static number of judgeships on the courts of appeals since Clinton took office. During Carter’s administration, Congress added thirty-five new seats to the appellate courts. Under the next two presidents, twenty-four (under Reagan) and eleven (under George H. W. Bush) new judgeships were created. However, since 1990, the total number of court of appeals judgeships has remained stable at 167.

GENDER, RACE, AND ETHNICITY

Historically, the federal appellate bench was almost entirely composed of white men. Before the election of Jimmy Carter, only two women had ever served on a court of appeals. Franklin Roosevelt appointed the first female federal appeals court judge, Florence Allen, to the Sixth Circuit in 1934. It took another thirty-four years before the second woman, Shirley Hufstedler, a Lyndon Johnson appointee, was appointed to serve on the Ninth Circuit (Ginsburg and Brill 1995).

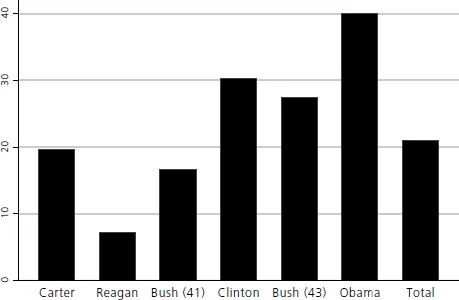

Beyond the two token women judges, the process of gender diversification on the court really began under President Carter. Figure 3 shows the proportion of court of appeals appointees who were women for each appointing president since 1977. Overall, just over 20 percent of judges appointed in the past thirty-four years were women. Two additional trends stand out in the graph. First, Democratic presidents have tended to appoint more women than their recent Republican counterparts. As the graph reflects, Carter appointed a larger proportion of women appeals court judges than did the two subsequent Republican presidents, and Clinton and Obama each appointed a larger percentage of women than did any Republican president. Indeed, during this time period, 27.5 percent of the Democratic appointees were women, compared to 16 percent of the judges appointed by a Republican. In other words, the last three Democratic presidents were 1.7 times more likely to appoint a woman than the last three Republican commanders in chief.

FIGURE 3. Percentage of U.S. Courts of Appeals judges who are women, by appointing president

Second, after accounting for partisanship, the general trend is toward appointing an increasing share of women judges to the appellate courts. Among Democrats, Clinton appointed about 10 percent more than Carter, and Obama appointed about 10 percent more than Clinton. A similar temporal pattern holds for the Republicans.

What accounts for these trends? The partisan difference may result at least in part from the gender gap—the tendency, since the 1970s, for women to affiliate with the Democratic Party more frequently than men (Norrander 1999). In other words, because there are more women Democrats and because presidents almost always select members of their own party, Democratic presidents are more likely to select women than are Republican chief executives. This preference is potentially compounded by the related presidential desire (though constrained by senatorial courtesy) to pick ideologically proximate nominees (Epstein and Segal 2005), combined with the tendency to perceive women as more liberal (Koch 2000). Finally, Democratic presidents appear to have had informal, if not formal, affirmative action plans (Slotnick 1984; Tobias 2010). The most obvious explanation for the tendency toward appointing more women (after accounting for partisanship) is an increasing proportion of women in the pipeline, which is roughly a reflection of the lagged proportion of women graduating from law schools. However, this does not appear to be the case. We can estimate the relevant lag by starting with the median age of judges when they are appointed, which, from the Carter administration through the first term of George W. Bush, has been fifty-one years. Assuming that the typical judge graduated from law school around age twenty-five or twenty-six years, the relevant lag is just under twenty-five years. In other words, the demographic breakdown of the total pool of potential federal appeals court appointees should be roughly reflected in the demographic breakdown of law schools thirty years prior to the appointment. Interestingly, twenty-five years before this writing, in 1976, approximately 10 percent of law school graduates nationwide were women (Sarver, Kaheny, and Szmer 2008). Five years before that, approximately two in one hundred law graduates were women. In other words, when the new judges added to the bench over the last thirty-four years were in law school, the pool of potential women judges was very shallow, and for most of this time it was miniscule.

In all likelihood, the trend toward more women appointees to the federal appellate bench resulted from several factors. First, the virtual quantum leap in the Carter administration—from one woman intermediate appellate court judge appointed in the previous five administrations to eleven appointed during Carter’s single term—likely owes at least in part to his innovations in the judicial selection process. Carter created a White House nominating commission for judicial appointees, and he encouraged senators to do the same (Ginsburg an...