![]()

The entire production process for a Hollywood motion picture – from development to theatrical release – typically takes from one to two years. During this time, raw materials and labor are combined to create a film commodity that is then bought and sold in various markets. Film production has been called a “project enterprise,” in that no two films are created in the same way. Nevertheless, the overall process is similar enough to permit a description of the production process for a “typical film.”

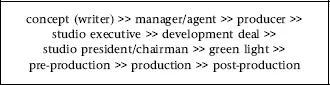

Contrary to popular belief, Hollywood films do not begin when the camera starts rolling, but involve a somewhat lengthy and complex development and pre-production phase during which an idea is turned into a script and preparations are made for actual production followed by post-production (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 From conception to development to production

Acquisition/development

I have an idea for a film, and if I had just a little more money, I could develop it into a concept. (Quoted in Cones, 1992, p. 97)

Ideas for Hollywood films come from many sources. Some screenplays are from original ideas or fiction; some are based on actual events or individual’s lives. However, a good number of Hollywood films are adaptations from other sources, such as books, television programs, comic books, and plays, or represent sequels or remakes of other films.

The prevailing wisdom is that around 50 percent of Hollywood films are adaptations. An informal survey of Variety’s top 100 films by gross earning for the years 2001 and 2002 and for all time revealed that Hollywood films often draw on previous works for inspiration. Books, biopics, and sequels to previous blockbusters represent primary sources used by the industry, while both comic book and video games represent emerging frontiers. Perhaps more importantly, films based on previous works consistently rated among the highest grossing films.1

Issue: Hollywood and creativity

These points draw attention to the issue of creativity, a topic that attracts a good deal of attention, both inside and outside of the industry. As we shall see, there are economic factors that contribute to this ongoing reliance on recycled ideas, already-proven stories and movie remakes and sequels. Repetition of stories and characters may also have cultural significance. Nevertheless, it is relevant at this point to at least question some of the extreme claims about the originality and genius of Hollywood fare.

Properties and Copyright

In Hollywood, film material rather quickly becomes known as property, defined by the industry as “an idea, concept, outline, synopsis, treatment, short story, magazine article, novel, screenplay or other literary form that someone has a legal right to develop to the exclusion of others and which may form the basis of a motion picture.” An underlying property is “the literary or other work upon which right to produce and distribute a motion picture are based” (Cones, 1992, p. 413).

The idea of a property implies some kind of value and ownership, and thus involves copyright law. In fact, copyright is a fundamental base for the film industry as commodities are built and exploited from the rights to specific properties. A copyright can be described simply as a form of protection provided by law to authors of “original works of authorship,” including literary, dramatic, musical, artistic, and certain other intellectual works. This protection is available to both published and unpublished works.

In the USA, the 1976 Copyright Act (Section 106) generally gives the owner of copyright the exclusive right to do (or authorize others to do) the following:

To reproduce the work in copies; To prepare derivative works based upon the work; To distribute copies … to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending; To perform the work publicly; To display the copyrighted work publicly, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work. (http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ1.html)

It is important to realize, also, that copyright protection applies only to the expression of an idea, not the idea itself. In other words, works must be “fixed in a tangible medium of expression” (Cones, 1992, p. 110).

A film idea that develops from another source usually already involves a set of rights. For instance, book contracts usually specify film rights.2 Thus, even before a screenplay is produced, ownership rights (and usually some kind of payment or royalties) may be involved. That is, unless a source is in the public domain, which means either that the work was not copyrighted or the term of copyright protection has expired. The material therefore is available for anyone to use and not subject to copyright protection. The rights to film ideas are often contested, with infamous lawsuits emanating from squabbles over copyright infringement, plagiarism, etc.

Overall, the Hollywood script market is relatively complex, as there are many ways that a script may emerge. An idea, concept or a complete film script may originate with a writer, an agency or manager, a producer or production company, a director, or a studio executive. In each case, a slightly different process is involved.

The players

Before describing the script market, it will be helpful to introduce some of the players involved in the process: writers, agents and managers, lawyers, producers, and production companies. In Hollywood, powerful people are often referred to as “players.” However, in this discussion, all participants in the process will be referred to as players, with the important distinction that some players are more powerful than others.

Writers. Everyone in Hollywood seems to have a screenplay or an idea for a film.3 It is not uncommon that directors or producers also are writers. However, only a relatively small number of writers actually make a living from screenwriting and typically writers have little clout in the industry.

In the past, writers typically had studio contracts or deals to develop ideas or options, from which scripts were written. More recently, a major writer works with an agent or manager to sell an idea or script (which sometimes is packaged to include talent) to a producer, who then tries to interest a studio executive in a development deal.

WGA. The Writers Guild of America is the collective bargaining representative for writers in the motion picture, broadcast, cable, interactive, and new media industries. The guild’s history can be traced back to 1912 when the Authors Guild was first organized as a protective association for writers of books, short stories, articles, etc. Subsequently, drama writers formed the Dramatists Guild and joined forces with the Authors Guild, which then became the Authors League. In 1921, the Screen Writers Guild was formed as a branch of the Authors League, however, the organization operated more as a club than a guild.

Finally, in 1937, the Screen Writers Guild became the collective bargaining agent of all writers in the motion picture industry. Collective bargaining actually started in 1939, with the first contract negotiated with film producers in 1942. A revised organizational structure was initiated in 1954, separating the Writers Guild of America, west (WGAw), with offices in Los Angeles, from the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE), in New York.

Salaries/Payments. While it may be difficult to determine how many people claim to be Hollywood screenwriters, it is even more difficult to assess how many writers in the industry actually make a living from their writing efforts. According to the WGAw, 4,525 members reported earnings in 2001, while 8,841 members filed a dues declaration in at least one quarter of that year. Thus, the guild reported a 51.2 percent employment rate. However, only 1,870 of those employed were designated as “screen” writers, and that group received a total of $387.8 million in 2001. (The highest number of employed writers were employed in television.) But the guild also points out that the general steady state of employment understates the turnover within the ranks of the employed, with as much as 20 percent of the workforce turning over each year.

While the minimum that a writer must be paid for an original screenplay was around $29,500 in 2001, much higher amounts are often negotiated (as discussed below). Writers also receive fees for story treatments, first drafts, rewrites, polishing existing scripts, etc. Other important earnings come from residuals and royalties. During 2001, the earnings of writers reporting to the WGAw totaled $782.1 million. The lowest-paid 25 percent of employed members earned less than $28,091, while the highest-paid 5 percent earned more than $567,626 during 2001.

Screen credits. Another area of crucial importance to writers (and other players) is the issue of screen credits, or the sequence, position, and size of credits on the screen, at the front and end of a film, and in movie advertisements. The order of front credits is often: distributor, producer or production company, director, principal stars, and then film title. However, there are variations. Credits or billing issues may be significant negotiating points in employment agreements and the guilds have developed detailed and often complex rules.

For instance, the WGA rules generally require a 33 percent contribution from the first writer for credit, while subsequent writers must contribute 50 percent. However, when an executive on a project also becomes a subsequent writer, such executives must contribute “more than 50%” to receive credit; if part of a team, that contribution must be “substantially more than 60%” for credit.

Credits are a vital issue for many Hollywood writers not only because of their impact on their reputations, but because bonuses and residuals are based on which writers receive final credit.

Agents/Agencies. Writers, as well as other Hollywood players, often use agents, managers or lawyers, to represent them in business negotiations and career planning. Generally, an agent or agency serves as an intermediary and represents a client. Agents typically negotiate employment contracts, sell scripts, help find financing, or act as intermediaries between two or more companies that need to work together on a project. The standard commission for agents is 10 percent, thus Variety’s name for agencies, 10-percenters. In addition, the agency gets an interest in possible future versions of the product (for example, a television show that is syndicated), in the form of royalties and residuals.

In California, agencies are licensed and regulated by the state through the California Talent Agency Act. Agencies also are certified by or are signatories of one of the guilds (the WGA or the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), discussed below). Some agencies are organized into the Association of Talent Agents (ATA), which has negotiated agreements with the talent unions and guilds for over 60 years. Another group representing agents is the National Association of Talent Representatives. In 2002, these two professional associations represented around 150 talent agencies (mostly in LA and New York), however, SAG and/or WGA also approved 350 other agencies.4

A few agencies are full-service organizations and handle a wide range of industry workers; others specialize in certain categories, such as actors or writers. Such organizations are either called talent agencies or literary agents, depending on what kind of talent is represented.

Agencies often are assumed to have tremendous clout and power in Hollywood, especially for their ability to put together film packages. The major talent agencies are closely held and many of their intangible assets are hard to value. But some aspects of the business – such as its ability to take a sizeable stake in the profits generated from packaging television shows – can generate substantial revenues.

CAA. The agency business became especially powerful in the late 1970s. Creative Associates Agency (CAA) was started in 1975 by a group of breakaway talent agents from the William Morris Agency, led by Michael Ovitz, who is given credit for greatly expanding the agency business. Initially an important television packager, CAA under Ovitz’s direction expanded into film, investment banking, and advertising, becoming the dominant talent agency in Hollywood. Ovitz also became involved in advising media companies and was credited with helping arrange the sale of several of the Hollywood majors in the 1980s, including MCA to the Matsushita Electric Company and Columbia to the Sony Corporation.

Under his aegis, CAA acquired a client list of some 150 directors, 130 actors and 250 writers, enabling Ovitz and his company to exert a dominant influence on major Hollywood productions through the packaging of talent. For instance, Ovitz was credited with putting together the major elements for successful films such as Rain Man and Jurassic Park. Even though agency packaging had been typical for TV production, such deals were more or less unheard of for film projects. Prior to the 1960s, the studios arranged projects through their ongoing contractual relationships with producers and talent. As the studio system evaporated, the door was open for others to make such arrangements. CAA stepped into this role when they began to assemble packages from their pool of directors, actors, and screen-writers. Consequently, the agency was able to attract more talent, who received increasingly higher salaries negotiated (or demanded) by CAA.

TABLE 1.1 Leading Hollywood talent agencies

INTERNATIONAL CREATIVE MANAGEMENT (ICM) - represents 2,500 clients in film, theater, music, publishing, and new media

- represents stars such as Julia Roberts and Mel Gibson

- owns stake in entertainment producer Razorfish Studios

- around $125 million in sales (1998)

- rumored to be worth between $100 million and $150 million

- CEO Jeff Berg owns about 30% of the agency

- 500 employees

| CREATIVE ARTISTS AGENCY (CAA) - founded in 1975 by a group of former William Morris agents

- represents clients in film, TV, music, and literature

- has a 40% stake in ad firm Shepardson Stern & Kaminsky

- offers marketing services to corporate clients such as Coca-Cola

- sales around $200 million (1999)

- 400 employees

|

WILLIAM MORRIS AGENCY INC. (WMA) - started in 1898 as William Morris...

|