![]()

Chapter 1

ANIMALS AND PEOPLE: MIRRORS AND WINDOWS

Zooarchaeology has begun to bore me. If I find myself reading, or for that matter writing, another animal bone report where the major conclusion is that an assemblage ‘contained 64 per cent cattle and less than 1 per cent deer, suggesting that people ate a lot of beef but that hunting was not very important’ (choose any of my reports and a similar statement will be there somewhere) I may have to commit suicide, academically speaking. In fact, this book is probably a major step towards achieving my scholastic death wish, as it presents a very personal, and perhaps not widely held, view about the aims and potential of zooarchaeology: my feeling is that we can do better and may need to if the discipline is to remain viable and respected.

For me, zooarchaeology is the study of animals – their remains, representations (artistic, linguistic or literary) and associated material culture – to examine the most fundamental issues concerning past societies: how people behaved and how they thought. Traditionally, zooarchaeologists, including myself, have shied away from tackling these big questions, instead passing the task, along with quantities of economic and environmental data, over to the ‘real’ archaeologists. I should, perhaps, not tar the whole zooarchaeological community based on my own shortcomings, as there are certainly many wonderful examples where zooarchaeologists have been at the forefront of archaeological research, asking cutting-edge questions about mainstream issues (e.g. Albarella and Serjeantson 2002; Arbuckle 2012; Barrett et al. 2004; Bartosiewicz 2003; Benecke 1994; Clavel 2001; MacKinnon 2004; O’Connor 2001; Outram et al. 2009; Pluskowski et al. 2011; N. Russell 2002; Twiss 2012; Vigne 2011; Zeder 1991, 2005). However, my impression is that these insightful works are in the minority relative to the large amount of zooarchaeological research that is undertaken worldwide. The situation is brought into relief further by the fact that some of the most exciting animal-based studies have been produced by scholars who would not classify themselves as zooarchaeologists (e.g. Conneller 2004; Crummy 2013; Fletcher 2011; Gardiner 1997; Hamerow 2006; Jennbert 2011; Larson 2011; Whittle 2012). For this reason, because faunal-remains specialists often stop short of interpreting the data they work so hard to produce, zooarchaeology is widely considered to be a facile data-generating specialism that provides little information beyond ‘what people ate’. As a result, funding for zooarchaeology is cut, particularly within the commercial sector, fatally reducing the specialist’s ability to provide any interpretation beyond mere dietary and economic reconstruction.

This problem is perhaps not helped by the university system. In the UK students are, quite rightly and vitally, trained to identify and record bones and teeth, to collate, analyse and present their data (64 per cent cattle, 1 per cent deer …), and to decipher any observable patterns (dietary preference for beef…) but they are not generally required to address bigger social and cultural questions about their material. And how could we expect them to do so? Time is limited, the literature that might feasibly help is dispersed widely and, by comparison to the many laboratory manuals for bone identification (Bocheński and Tomek 2009; Cannon 1987; Cohen and Serjeantson 1996; Hillson 1992; Pales and Lambert 1971; Schmid 1972, Walker 1985) and text-books on analysis (Chaplin 1971; Cornwall 1956; Davis 1987; O’Connor 2000; Reitz and Wing 2008), there are few volumes dedicated specifically to the interpretation of zooarchaeological material: N. Russell (2012) is a notable exception, her important volume published whilst I was writing this book.

In the absence of accessible texts it has been difficult to teach ‘social zooarchaeology’, so cohort after cohort of zooarchaeology students graduate without really understanding the true value or great potential of the data at their disposal. I was one such graduate. At university I received exemplary tuition in the theory and methods of animal bone analysis, trained to a standard where I was a competent commercial specialist. I spent several years producing data-heavy/interpretation-lite faunal reports before becoming a university lecturer, a role that enabled me to equip new generations of students with the ability to follow in my tedious footsteps. I would now like this cycle to stop. So, I have written this book. I hope it will encourage reflection on the core methods and ambitions of archaeological animal studies and highlight the potential for zooarchaeologists to make a contribution not only to archaeology but also to disciplines outside our own field.

The discussion presented here is centred primarily on my own research, which focuses on British material dating from the Iron Age to the post-Medieval period, but the approach I advocate is, I believe, applicable to any assemblage from any period or place. My overarching aim is to encourage zooarchaeologists to take control of the evidence at their fingertips, to demonstrate to the archaeological profession that zooarchaeology is a varied and highly skilled discipline that provides vital evidence to answer significant questions about any culture under consideration. Essentially, animals should be at the centre of archaeology’s research agendas

To take a stand, however, requires that we have something to stand upon. Fortunately, zooarchaeology has exceptionally strong foundations, built during the decades of Processual Archaeology, when many of the discipline’s most important methods were developed and influential texts written (e.g. Binford 1978; 1981; Brain 1981; Grant 1982; Legge and Rowley-Conwy 1988; Payne 1973; Shipman 1981; Speth 1983). These cornerstones of zooarchaeology have stood the test of time but, as with all great works, they now require some renovation. In the following sections I will contemplate some of the fundamental principles and methods of zooarchaeology and consider if it is time to take a new perspective on some of our approaches.

Step One: Considering the Bones

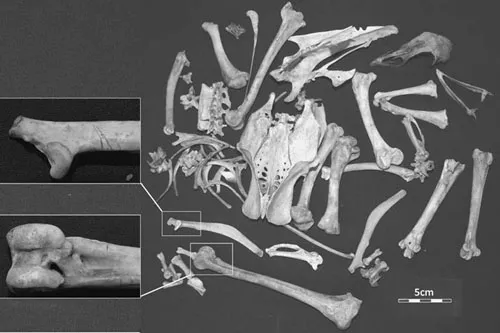

Figure 1.1 shows an assemblage, the kind that might be encountered on any archaeological site. With the use of a reference collection and laboratory manuals it does not take long to identify that all of the specimens in the assemblage are bird bones and, more specifically, that they belong to domestic fowl (Gallus gallus).

Closer inspection indicates that most parts of the skeleton are present – head, vertebral column, wings, legs and feet – and that, in all probability, the specimens come from a single individual: in no case are there more elements than would be expected from a one skeleton. Looking at the two tarsometatarsi, cock-spurs are absent, suggesting that the individual is probably female, and we may assume that it was an adult as the bones are all fully developed. Taking the analysis further, measurements of the bones highlight that this particular chicken is very large indeed, most probably the product of a programme of selective breeding for carcass size. The idea that the animal was raised for meat is perhaps borne out by the cut marks visible on several of the bones, most probably made when the carcass was disarticulated for consumption. That the whole skeleton was deposited together, despite the fact that it was butchered for food, could indicate that the individual was afforded special treatment and may reflect the refuse from a religious-ritual feast. Why this might have occurred is less easy to determine but it could relate to the ‘exotic’ status of domestic fowl: as with most domestic animals, they are not native to many of the areas of the world where they have been imported (Chapter 4; Sykes 2012).

Figure 1.1 An assemblage of very large chicken bones. Several show evidence of butchery (see insets).

Source: Sykes.

As far as the above interpretation goes, which is probably as far as is found in most zooarchaeological reports, it is largely accurate, although the chicken is actually a male rather than a female. I know this because this particular ‘assemblage’ of bones comes from a cockerel, Gunter, who I lived with for almost a year (Figure 1.2).

Gunter hatched on 14 June 2010, matured into a magnificent cockerel by October that year but by February 2011 he had become so noisy and sexually aggressive toward the hens that we decided to eat him (to legitimize killing him). As a culinary experience Gunter was memorable for the wrong reasons, reaching unusual levels of toughness: had we wanted him to be less chewy we should have killed him many months earlier. Most of my memories of Gunter are of the time we spent together whilst he was alive, when his beauty, sound and overly virile behaviour was hypnotic, though often disturbing. The relationship that my family and I had with Gunter was very real and very different to the relationship that we had with another cockerel, Nightshade (also recently dispatched). In the case of both Gunter and Nightshade we valued them more in life than in death and I would go so far as to say that the two cockerels, together with the hens – Marley, Mimble, Little My, Mimi, Bronte, Perdix and Pidge – have changed my family’s life, lifestyle, diet and our local landscape. For instance, these free-range creatures have not only altered how our garden looks, sounds and smells but they have also transformed the way that we engage with the space on a daily basis. We now spend time looking for eggs, dodging dustbowls and avoiding or collecting the huge amount of shit that they produce. They have even changed the life of our cat, Waggers, who has socialized with them sufficiently to overcome his original desire to eat them, restraining himself even when, as fluffy chicks, they snuck into the house, pushing past him to eat from his food tray.

Figure 1.2 Gunter the Magnificent.

Source: Paul Morris.

Spending time with our chickens and cat, and observing their impact on my own behaviour, made me realize that my relationship with these animals was far more complex and interesting than anything I attributed to archaeological assemblages. It made me appreciate the work of Armstrong Oma (2010), Brittain and Overton (2013) and Mlekuž (2007) who have argued that human–animal interactions transform both parties, the two becoming mutually socialized through their exchanges. This has made me reconsider the way I think about and interpret zooarchaeological material. Critics will argue that I am anthropomorphizing the animals that I live with, attributing them with names, characters and thoughts of which they are oblivious. Critics will believe that I am a ‘bunny hugger’ with little understanding of the kind of relationship that ‘real’ farming communities, both now and in the past, have with animals.

To some extent these criticisms are fair and I accept that my relationship with Waggers the cat, Gunter and the hens (all of whom will reappear throughout this book) and my experiences of living with them are unlikely to be representative of the relationships and experiences of other people in time and space. The insights I have obtained are largely personal, reflecting my individual worldview. But the fact that my relationship with the chickens is such a close reflection of my wider life concurs with the growing body of evidence from human–animal studies, which highlights that the way that people think about and treat animals is a ‘mirror’ of, or provides a ‘window’ into, how they treat and think about each other (e.g. Mullin 1999). I am aware that scholars such as Mullin no longer subscribe to the mirror/windows metaphor, instead seeing human–animal relationships in terms of ‘mutual becomings’; however, I like the mirror/windows concept and will use it as a central device throughout this book.

Whatever their theoretical stance, anthropologists, sociologists and cultural geographers all recognize that human–animal interactions are a key source of information for understanding human societies and cultural ideology (e.g. Bulliet 2005; Ingold 2000; Knight 2005; Mullin 1999; Philo and Wilbert 2000; Wilkie 2010; Wolch and Emel 1998). Given that other disciplines appreciate the value of animal studies, archaeologists have been remarkably slow to come to a similar recognition. The situation is made stranger still given that, on many archaeological sites, animal remains are the most common find. In fact it could be argued that the bulk of the archaeological record is composed of debris from human–animal interactions, be it in the form of animal remains, animal-related artefacts (e.g. horse gear, cooking pots, butchery tools, animal figurines) or entire landscapes.

I wonder if our failure to extract decent social information from archaeological animal data is due, in part, to the rationale behind current zooarchaeological methods: whilst the techniques of quantification, ageing and sexing are essential to zooarchaeological work, most were created to ascertain the productive rather than cultural significance of animals. It would take, however, just a small shift in mindset to gain a less familiar but more engaging perspective on past societies.

Step Two: Considering the Methods

It is important to stress from the outset that although this book is not concerned with ‘practical’ zooarchaeology in the sense of identification and laboratory methods, I agree completely with Reitz and Wing (2008: ix) when they state that ‘theoretical interpretations are no better than the methods used to develop supporting data. It is as necessary to be well-grounded in the basics as it is to be guided by good theory’. It is imperative that any data collection is undertaken to the highest possible standards and I would refer the reader to a good reference collection and the works of Reitz and Wing (2008), Davis (1987) and O’Connor (2000) for guidance about how field and laboratory work should be conducted. Due consideration must also be given to issues of taphonomy and all researchers should have Lyman (1994) in their library. Once the data are collected, however, there is scope for re-thinking how we consider results derived from them.

Taxonomy: The Classification and Categorization of Animals

For me, one of the most unnerving aspects of zooarchaeology is taxonomy. The scientific classification system to which we all adhere – namely the Linnaean system – underpins and dictates the direction of all our zooarchaeological analyses, providing neat and internationally recognizable categories such as Sus scrofa or Lama glama into which we can drop our animal remains. From the perspective of methodological standardization, this is a very good thing. However, given that the Linnaean system is a product of the eighteenth century its applicability to societies that pre-date its invention is questionable. Even in our society, few of us in our day-to-day life actually categorize animals based on the Linnaean system: according to my youngest daughter’s favourite book, ‘C...