![]()

1

The Idea of Political Liberalism

I.The Liberal Hypothesis

It is fairly common to assert that the type of political order that prevails in Western democracies is ‘liberal’. Every participant in that type of order has some idea of what its liberal quality means. It is associated with the ideas of majority rule, representation, elections, individual rights, constitutionalism, a market economy, the values of tolerance and freedom, as well as a view of individuals – ordinary human beings – as worthy of concern and respect. But it is not clear at all what (if any) is the connection among these ideas.

This is not a quibble. The presence or absence of a connection among the ideas suggests two quite different accounts of the character of ‘liberalism’ as a predicate of a political culture. One account – call it nominalist – understands these terms as a hodge-podge of elements that are named ‘liberalism’ in conjunction; what makes a political culture ‘liberal’ is that the mainstream is seriously committed to all or most of the ideas listed above and pays tribute to the institutional arrangements – eg, an electoral system based on universal suffrage – that they vindicate.

A different account – call it holistic – suggests that these various elements somehow form a system in which the meaning of each is partly determined by its relationship with the others and, more generally, with the entire set of relations that constitutes the system itself. A useful analogy is with language.1 Although words – say, ‘chalk’ – have some meaning of their own, their full meaning within a language is largely a function of a system of relations among terms.2 In our example, the same term referring to the same substance – chalk – has a meaning in relation to the system of minerals and quite another in relation to the set of items in the classroom experience; and expressing the term in conjunction with others in the same system elicits a particular sequence of images – eg, the teacher writing on the blackboard – that enables knowledge of how it fits into, or is a part of, a meaningful whole.3

I want to provide a holistic account of liberalism. Liberalism is not a hodge-podge, but a whole in relation to which ordinary liberal commitments acquire a specific meaning. Since we are talking about ideas and beliefs with social currency, it is appropriate to speak of liberalism as a form of consciousness or an idea immanent in our political culture.

The task looks entirely familiar. There are many fine scholarly efforts to define or account for the essence or constitutive premises of liberalism.4 But any proposed definition of liberalism – say, ‘equal freedom’5 – is likely to appear problematic, for at least two reasons. The first is that it is so abstract that its connection with actual, verifiable, liberal commitments is either lost or unclear; in other words, a definition of that sort – at the outset – looks arbitrary, unless you happen to agree with it already. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that sometimes no clear line is drawn between liberalism and the particular version or working out of liberal ideals that the scholar happens to favour. The second problem is that there are (at least apparently) different uses of the word ‘liberalism’ in political discourse. We speak about liberals versus conservatives, about liberals versus Marxists and conservatives, about liberal democracy, about the classical liberalism of Locke, Mill and Kant; the relation – if any – among these various uses of the same word is obscured by a definition of ‘liberalism’, even if it is explained which of the various uses is in question. To sum up: the problem with definitions at the outset is that they are entirely stipulative.

Liberalism is both ubiquitous and mysterious. My purpose is to show what it is from the standpoint of those elements and practices that everyone associates with ‘liberalism’. My aim is hence twofold: to explore the substance of liberalism and to establish its social currency. Of course, my task is greatly facilitated by the existence of a large body of literature that is concerned either with liberalism or with making claims and arguments that are taken to be important contributions to liberalism; but what I want to establish is the connection between theory and practice, between ideas in books and beliefs held by agents out there in the social world. For that reason, my method is quite different from the familiar form of ‘definition at the outset’ and the order in which I present the arguments is different from the familiar structure of an article or book on liberalism. I will depart not from ‘first principles’ but from what I take to be verified liberal commitments, of the sort listed in the first paragraph, and proceed from them to less obvious commitments. If I am right – if indeed there is a liberal form of consciousness – what will make the move from something obvious to something less obvious intellectually compelling is that my reader, as a participant in a liberal political culture, will recognise the relations among the various terms. The analogy with language is useful again. Most people know how to use the various terms that constitute a system of relations – in the classroom language game: ‘chalk’, ‘teacher’, ‘blackboard’, ‘school’, etc – even though they are neither aware of them nor understand their interrelation. Trying to understand the system is to bring it to full conscious awareness.

*****

We employ as a rule the term ‘liberalism’ in ordinary political discourse in order to refer to what is typically a major current of opinion in contemporary democracies regarding the proper organisation of society and the policies that the government should adopt. The meaning of the term – the set of properties that constitute the essence of liberal politics – varies quite drastically along both temporal and spatial lines. There are important distinctions to be drawn, for example, between old and modern liberals, classical or ordo- and social or egalitarian liberals, European and American liberals.

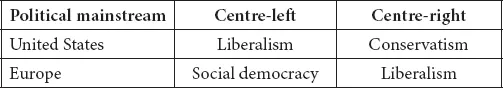

Perhaps the most interesting and surprising contrast to be drawn concerns the very different position that American and European liberals occupy in the political spectrum. In the United States, liberals are on the center-left. They tend to support, among other policies, substantial economic regulation, jobholding policy, the growth or at least preservation of the welfare state, progressive taxation and income redistribution, affirmative action, abortion rights and same-sex marriage, a sociological account of crime and a rehabilitative conception of punishment. This incomplete list is formed by typical features instead of a set of necessary and sufficient conditions; hence, one may well be a liberal without subscribing to every element in the list. Liberals in North America oppose conservatives, the other major current of political opinion. The conservative’s typical commitments are symmetric to the liberal’s. They include light regulation, free enterprise, small government, flat or regressive taxation, color-blindness, pro-life and traditional family views, an individualist account of crime and a retributive conception of punishment. In European politics, on the other hand, the term ‘liberal’, to the extent to which it is even used, has the opposite connotation. A typical liberal in Europe holds, very roughly speaking, the positions of a typical North American conservative. On the other side of the fence lies the social democrat, who in many respects is what an American would call a liberal. A simple matrix captures the point.

Figure 1.1Liberalism in ordinary politics

That the same term came to mean almost exactly opposite things in the two most stable political cultures of the democratic world should not pass unnoticed. The fact is telling in two apparently contradictory ways. On the one hand, it signals that there is likely something entirely contingent in the history of the term ‘liberalism’. If North American liberals hold roughly the same commitments as European social democrats and, as a result, the contrary to the those of European liberals, the term itself means very little except within a particular political culture in which it has acquired stable meaning. It was up for grabs and someone grabbed it. On the other hand, there is ample room for the hypothesis that in some way both American and European liberals can claim to descend from some older political tradition from which the term arose. Of course, if that is true, there is a sense – certainly a deeper and partly concealed sense, different from the one that counts in everyday political talk – in which North American liberals and conservatives, as well as European social democrats and liberals, are all liberals. Since the term liberalism carries a deep and concealed, as well as a surface and transparent, sense in our political discourse, the apparent contradiction between the two historical accounts of that term – as a member of our shared political vocabulary – is dissolved. The appropriation of the term at the level of surface or ordinary politics was indeed contingent and arbitrary, something in the order of events; but the term which came to be appropriated – liberalism – originated at a deeper level, which constitutes the foundation of the mainstream of democratic politics all over the world. That, at any rate, is the hypothesis.

The hypothesis – let me restate it – is that all mainstream parties or currents of political opinion in contemporary democracies descend from the same body of political ideas – liberalism. But this formulation is not wholly satisfactory, because references to an idea or a body of ideas descending from another one are systematically ambiguous. All point to the existence of a common ancestor. Nevertheless, common ancestry may be of two sorts; let me call them genealogy and prototype.6 Genealogical ancestry resembles a family tree. The present generation is a function of marriage and reproduction between members of two different families; each child is produced by the sexual encounter of his parents, who belong to different lines of ancestry. Each of the parents, of course, is the result of a similar encounter between members of different families; and so on and so forth. Children are not generated by a single parent, but by two parents, typically unrelated by blood. Siblings born of the same parents are full siblings. If the same individual happens to reproduce with two different partners, the children born of each relationship will not be full but half siblings. They have one biological parent in common.

We may reasonably suppose that liberalism is the common ancestor of all major parties of political opinion in democratic politics, such as North American liberalism and conservatism, because it is a common doctrinal parent to them. They all inherit one set of distinctively liberal ‘genes’. However, each of them has a different second parent. It is plausible to assert, for instance, that American liberalism is the offspring of the marriage of classical liberalism with socialism, while conservatism is the child of classical liberalism and something like traditional conservatism. We would then be right to reserve the term liberalism to a pool of doctrinal genes that is shared across the centre or the mainstream of the political spectrum in stable democratic cultures such as the United States or the European Union. That is the genealogical version of the descent hypothesis that mainstream democratic politics has a common liberal ancestor.

But that is not the account of liberalism I shall provide. Mine is the prototype version of common ancestry. A prototype is an early model or crafting effort of a design concept or an idea. The main functions of the prototype are pedagogic and experimental: pedagogic because it increases our awareness of the design concept or idea that it embodies; experimental because the prototype is a primitive attempt to attain a certain ideal, the design concept or idea, an attempt from which one can learn how to fashion a better model. Both liberalism and conservatism, on this account, purport to be improved models of some design concept that was embodied in an original prototype. For reasons that I hope to make clear later, the prototype in question is the classical eighteenth century liberalism that achieved final form in the political theory of Immanuel Kant. What the modern liberalism and conservatism of North American politics represent, as well as their substantive equivalents in other democratic cultures, are rival attempts to improve on that earlier prototype, based on somewhat different assessments of the strengths and weaknesses of the original model. It does not, of course, harm my case prima facie that there may be more than two contenders in a particular democratic culture among the many that I have failed to even mention, or that the contenders in question may not be analogous to those that seem to dominate the American political scene. All that I have to show is that all variants of mainstream democratic politics proceed from a common prototype.

The nature of the task ahead becomes clearer once we acknowledge the distinction between the prototype and the design concept or idea. The former is a model or test case of the later; the prototype is designed and built to embody the idea. In every prototyping enterprise, then, we have to distinguish a constant from a variable part. The constant part is the design concept which the engineered prototype purports to embody, while the variable part is the model itself. What remains constant across a more or less long series of modelling efforts is the design concept, although by virtue of the pedagogic function of prototyping it is highly likely that our awareness of the concept increases as the modeling sequence progresses.

I should insist that these matters are definitional. It is perfectly possible, of course, that a prototype may serve as an inspiration for a radical shift from one design concept to another. Yet where that occurs it is no longer correct to say that the prototype in question is the first of a single sequence of modelling attempts. What we have is a different project altogether. My aim is to clarify the concept of a prototype in order to improve our understanding of my initial hypothesis; that liberalism is the shared root of the major parties of opinion in contemporary democratic politics.

If the classical liberalism that is so well represented in Kant’s work on political theory is the best prototype of both liberalism and conservatism, the design concept or idea of which it was a prototype is what I will call liberalism. It is the ‘design concept’ of our political culture. I have not so far given even the slightest hint as to what that concept might be, much less have I showed that it is real. (In due time, we shall see that the two tasks are deeply intertwined.) Although that must be infuriating even to the most patient of readers, it was necessary first to make entirely clear the nature of the hypothesis that I am yet to confirm: it is the view that liberalism and conservatism, as well as other mainstream parties of opinion in democratic politics, descend from the same prototype, and share both among themselves and with that prototype a single design concept or idea that may be properly called liberalism.

Before we test the hypothesis, let me enrich it with the notion of incorporation. What I have in mind may be clarified with an analogy. Suppose that two car manufacturers – A and B – are each developing a new car for roughly the same market niche. Both teams of engineers have conceived a certain concept for the new car and have built a prototype to test it. Now imagine that spies hired by A manage to steal the plans developed by the engineers working for B. The plans are then given to the team of en...