![]()

Part 1

It’s a man’s world

![]()

Chapter 1

Two pieces of cavalry helmet from the province of Gelderland

Annelies Koster

The largest number of Roman helmets found in the Netherlands have been from dredging operations in the river Waal, near Nijmegen and to a lesser extent further east in the vicinity of Millingen and Pannerden (Klumbach 1974). More helmets and helmet parts have also come to light in Nijmegen, found in archaeological excavations and by members of the public, i.e. from the Kops Plateau and the St. Josephhof (van Enckevort and Willems 1994; Junkelmann 1996, 93, O83–6; Meijers and Willer 2007, 21–30; van Enckevort 2007). In recent years several more helmet parts were found following large scale earth removal and dredging operations, carried out in the eastern river area during the “Room for the River” program. Despite detailed archaeological research preceding such large scale operations, some finds may still come to the surface after the excavations have taken place. This is the unfortunate reality of the methods employed by these earth removal operations. Sometimes amateur archaeologists are permitted to search the dumping ground or the gravel depot with metal detectors. However, they do not always report their finds.

This was not the case for an extraordinary bronze face mask from a Roman cavalry helmet, which the Museum Het Valkhof gratefully received in 2015, as a long term loan from the territorial development firm K3Delta (inv. no. 2015.135). The mask had been found in 2014 by two metal detectorists searching the gravel depot belonging to K3Delta in De Steeg (gem. Rheden). It is thought that the face mask may have been dredged up with the sand and gravel from the river bypass at Nijmegen. However, it is also possible that the mask comes from earth removal and dredging operations in the vicinity of Rees on the Rhine (DE), as the sand and gravel from both locations were stored together in the depot. So there is no absolute certainty as to the find location.

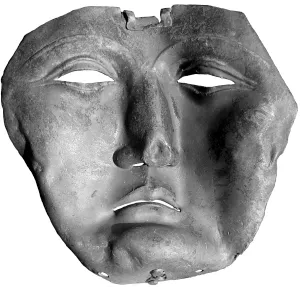

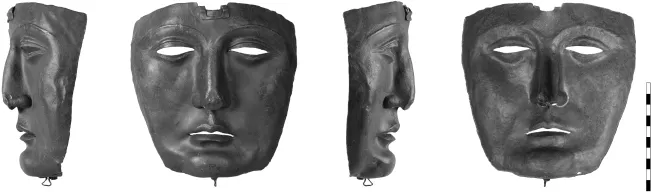

The bronze mask, which was somewhat dented when it was found (Fig. 1.1), has been restored to its original shape by the archaeological restorer Johan Langelaar from Amersfoort (Fig. 1.2 and Plate 1).

The face mask (H: 170 mm W: 160 mm) was cut from a sheet of copper alloy of 1–2 mm thick. At the tip of the nose the sheet bronze was hammered extremely thin, allowing it to damage easily. The tip of the nose has been dented, deformed and cracked and seems to have been repaired on the inside in Roman times with some tin. The dent on the nose could possibly have been the result of a slap in the face during a fight.

Figure 1.1 Face mask as it was found, before restoration. Photo: Johan Langelaar, Amersfoort

Figure 1.2 Front, back and side view of the mask after restoration. Photos: Museum Het Valkhof, Ronny Meijers, Nijmegen

The forehead of the mask is extremely low and the missing bowl of the helmet must have protected a large part of the forehead. A hinge above the nose originally connected the face mask to the bowl of the helmet.

The face looks stern and expressionless. The eyebrows are thin and arched and the cut-out eyes are narrow and oval. They are quite like those from most other face masks, and are pronounced by the stylised eyelids. The nose is strong, long and narrow with large nostrils. The mouth is small and well proportioned. It is also open, allowing the wearer of the mask to breathe.

The holes on both sides of the round chin were probably designed to provide additional connecting points between the face mask and the helmet. Some face masks have bronze studs in these holes, to which leather connecting straps could be fastened. For instance, the face mask from Vechten (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden (NL), inv. no. VF*1047) also has holes on both sides of the chin (Klumbach 1974, 64, no. 54; also see for fastening the mask to the helmet, Hanel and Willer 2009, 211, abb. 2). But most face masks of this type do not have holes under the chin. This could mean that the masks were held in place by the cheek pieces instead.

In addition to the two holes, a bronze loop, fixed with two rivets, was attached under the chin of the face mask (Fig. 1.3). Maybe the fastening with the bronze studs alone did not function well enough. Through this loop a leather thong could be guided across the cheek pieces to the back of the helmet and fastened there.

The face mask is part of a Pseudo Attic cavalry helmet of the Kalkriese type. It is characterised by the low forehead with hinge, by which the mask was fastened to the helmet, and also by the absence of ears. This means that the helmet should have had cheek pieces with preformed ears (Born and Junkelmann 1997, 18–21). The most well-known and best dated face mask of this type was found in Kalkriese near Osnabrück in 1989/90. It was most likely lost in the battle between the Roman troops and the Germanic tribes in AD 9 (Franzius 1993, 131–5). The Kalkriese face mask was of iron and originally covered with silver foil, parts of which have been preserved under the bronze border that frames the mask (Franzius 1993, 131; Willer and Meijers 2007, 31–50; Hanel and Willer 2009).

Figure 1.3 Chin of the face mask, before restoration. Photo: Johan Langelaar, Amersfoort

Two masks of the Kalkriese type are known in the Netherlands: one of iron was found on the Kops Plateau in Nijmegen and dates to sometime before AD 70, based on dates for the military presence there (Willems 1991, 12; on loan in the Museum Het Valkhof, inv. no. 2017.2). The other iron mask, covered with sheet bronze, was found during the construction of fort Vechten between 1867 and 1869. Klumbach (1974, 64, no. 54) dates this mask to the second half of the first century, on obscure grounds however.

Meanwhile about ten pieces of the Kalkriese type face mask are now known. Born and Junkelmann (1997, 18) mention seven of these pieces, but recently more pieces have come to light in the art trade and also in private collections (Humer 2006, 103–4, no. 340, abb. 39; Christies Sale 14230, Antiquities, 5 July 2017, London, lot 133). Some were found together with their helmet bowls and/or cheek pieces. One was a bronze mask from a helmet of the Weisenau type (Junkelmann 1996, 93, O88), a type of helmet from the first quarter of the first century AD, which was most likely also used by horsemen of the Celtic auxiliary cavalry (Junkelmann 2000, 42). There is also an iron face mask, covered with sheet brass, which was found together with an iron helmet bowl, covered with richly decorated sheet bass in relief. This helmet is of the Weiler/Koblenz-Bubenheim type (Junkelmann 1996, 84–8). Another bronze face mask was found together with two cheek pieces with ears, like the ones of the Weisenau and Weiler types (Humer 2006, 103–4, no. 340, abb. 139).

Figure 1.4 Both sides of the brow plate. Photos: Museum Het Valkhof, Ronny Meijers, Nijmegen

It can be proven that these face masks were actually part of cavalry helmets by the inscription TVR (ma) PAVLI FVSCI (cavalry squad of Paulius or Paulus, possession of Fuscius or Fuscus) written on the side of an iron face mask, covered with a tinned sheet of brass (Junkelmann 2000, 189–90, taf. xxi, from unknown findspot).

Junkelmann sketched the typological development of these face mask helmets from the late Augustan period, in which the Kalkriese type – the type without ears on the mask and with a hinge low on the forehead – seems to belong at the beginning of the series. This type of mask seems to have been in use until the middle of the first century, as part of the helmets of the Weisenau and Weiler types.

The mask could be lifted upwards, without the helmet falling apart in two pieces. The helmet bowl always remained firmly fixed to the head. Experiments have also made it clear that the helmets may also have been used in cavalry battles. The relatively large openings in the mask provided enough sight and also allowed enough fresh air for the rider to engage in mounted combat (Born and Junkelmann 1997, 18–21, 31).

Above all, research by the LVR-Landesmuseum in Bonn and the Museum Het Valkhof, has demonstrated that the combination of iron and bronze from which these face masks were made, was highly resistant to damage. It provided the horseman with effective protection against attacks to the face (Meijers and Willer 2007).

These early first century face masks – like the helmets of the Kops Plateau type, dating around the mid-first century AD – seem to have been primarily made for use in battle and not just in tournaments or hippika gymnasia, as was often assumed (Künzl 2008, 112–4). In the second and third centuries the construction of these cavalry helmets changed, which made them unsuitable for the battle. Most likely by then they were only ceremonial in function, perhaps used as parade helmets.

A second part of a cavalry helmet was found in 2015, in a heap of clay and sediment at the earth removal and dredging operation in Millingerwaard (northwest of Millingen aan de Rijn). It is a bronze brow plate of a cavalry helmet, relief embossed from sheet bronze, which was subsequently tinned to give a silvery look (on loan in the Museum Het Valkhof, inv. no. 2016.15). Originally the brow plate was crescent-shaped, but was found in a folded and slightly bent condition. These deformations though may well have been the result of the dredging operations.

The brow plate is divided in three horizontal zones, separated from each other by pearl and ovolo borders. The middle zone, between the two ovolo borders, is decorated with a wreath of oak leaves, in three leaf fascicles, set against a background of punches (Fig. 1.4). This zone ends with a rosette on both sides of the brow plate. But part of the rosette on the left side is missing however. Holes for fixing the plate to the helmet are visible on both ends, situated behind the rosettes, and also on the front, in the center of the brow plate (Fig. 1.5).

The decoration on the upper zone consists of a waves motif, rolling from the centre of the plate to the left and to the right. Again the background of this decoration is punched. The center of the brow plate is decorated with a crescent-shaped, floral motif, with large curly petals and a rosette in the center (Fig. 1.6). The background of this floral motif is also punched. The lower zone of the plate, between the ovolo and pearl borders, is undecorated.

These bronze, mostly tinned, brow plates were applied to iron cavalry helmets of the Weiler/Koblenz-Bubenheim type, dating to the second quarter of the first century (Born and Junkelmann 1997, 17ev?). A cavalry helmet of this type from the river Waal near Nijmegen has a comparable bronze brow plate, decorated with a wreath of oak leaves, which are embossed in high relief (Braat 1939, 40–2; Robinson 1975, 98–9; Klumbach 1974, 46–7, no. 33; Heijden and Koster 2017, 23). Another brow plate with a wreath of oak leaves also came from the river Waal near Nijmegen and is decorated in the same way (Braat 1939, 39–40; Klumbach 1974, 47–8, no. 34, taf. 34; Robinson 1975, 99, no. 272).

We should assume that the soldiers wearing helmets decorated like this, did not do so because of their beauty. The wreath must have had a special meaning for them (cf. for instance the helmet of the Weiler/Koblenz-Bubenheim type from Xanten with the gilded wreath of olive leaves and olives: Prittwitz und Gaffron 1991, 237–9; Prittwitz und Gaffron 1993). The oak wreath, the corona civica, was reserved for Roman citizens who had saved the life of a fellow citizen. Most likely the corona civica, was chosen on purpose as the decorative motif for these helmets. The horsemen wearing the helmets may actually have been awarded these insignia. In this way they could show their wreath permanently on their helmets, allowing them to distinguish themselves from their colleagues. It means also that these cavalry helmets, with corona civica, must have been used by Roman citizens, serving in a cavalry unit. The horseman could therefore have served in the cavalry unit of a legion, or as...