![]()

1

YEARS OF CRISIS, 1918–23

Considering what came afterwards, it is perhaps significant that the Weimar Republic came into being almost by accident. The proclamation of the republic on 9 November 1918 was not the result of a detailed political programme or a long hard-fought campaign, but a reaction to events and an attempt to divert the people’s energies from a more radical course. Yet the fact that democracy was thrust upon the German people should not mislead us into thinking that Weimar was, as has been so often asserted, ‘a republic without republicans’. In fact, as recent research has shown, there was a surprising degree of consensus over the constitutional settlement of 1919, which incorporated both many of the long-cherished ideals of the liberals and social democrats, and the desire of the conservatives for a strong executive. Nevertheless, there were still those in Germany who opposed the new regime, and a sizable minority on both the Left and Right to whom the republic itself was anathema. These forces determined to use whatever means they could to overturn the constitution, making its early years ones of turmoil in which the moderate parties struggled for stability in the face of extremist pressure. This led them to make some fateful compromises which were to have far-reaching implications for the fate of the republic.

THE DOMESTIC IMPACT OF THE WAR

By the autumn of 1918, Germany and its allies stood upon the brink of collapse. Four years of total war had sapped their manpower and morale, and only deepened existing social and political divisions. As casualties mounted and conditions on the home front deteriorated, the fragile political consensus reached in 1914 began to crack and the government faced growing opposition on the streets and in the Reichstag. The final straw was the realization that the war was lost and all the suffering and hardship had been for nothing. When this became clear, the political edifice created by Bismarck nearly half a century previously began to crumble, leaving anarchy and uncertainty in its place.

Together the Central Powers lost over 4 million men during the hostilities. Of the 13 million Germans who marched off to war between 1914 and 1918 around 2 million never came home at all, while of those who did return 4.2 million did so bearing the physical wounds of their wartime experience. Even those who escaped physical harm carried psychological scars, and few returned from the front unaffected by what they had seen and done. Roughly 19 per cent of the adult male population were direct casualties of the war.1 As more and more men were thrown into the meat grinder of the trenches, as the quantity of rations and quality of equipment deteriorated and news of wartime shortages on the home front filtered through to the fighting men, morale began to suffer. While discipline amongst soldiers at the front on the whole remained strong, behind the lines it was a different matter. One in ten men transferred from the eastern front in 1917 deserted while in transit, and by September the Berlin police estimated that there were around 50,000 deserters in the capital alone. By the summer of the following year as many as 100,000 men had deserted, while mutinies broke out in Ingolstadt, Munich and Würzberg.2

These ominous signs of military unrest were mirrored by growing dissatisfaction on the home front. Before the war Germany had imported around one third of its food, and with the Allied blockade in place no amount of rationing or Ersatz (substitute) foods could solve the problem of shortages and high prices. The nutritional value of the German diet plummeted and cases of malnutrition and rickets soared, especially amongst children. During the so-called ‘turnip winter’ of 1916–17 an early frost destroyed most of the potato crop, forcing the majority of the population to survive on a diet of turnips. Few Germans actually starved to death, but many were desperately hungry and the search for food and fuel became a full-time occupation for many older women. In this the Germans were more fortunate than their allies. By 1918 the Austro–Hungarian food supply had broken down completely and famine had gripped the Empire. Between 7 and 11 per cent of civilian deaths in the Austrian capital Vienna were as a result of starvation, and people were expiring in their homes or dropping dead in the streets.3 In both Vienna and Berlin a flourishing black market grew up, which only increased public anger and exacerbated existing social tensions. The middle classes viewed those who relied on state and charitable assistance as freeloaders, while the poor resented this attitude and felt humiliated by their dependence on handouts. However, both groups reserved their greatest anger for the wealthy, whose lifestyle seemed unaffected by the war.

All this had a radicalizing effect on the German population, leaving both men and women more independent, less pliant and deferential, and determined to challenge social convention and live life to the full. Women and adolescents increasingly moved into the labour force to take the place of men conscripted into the army, creating a huge pool of unskilled workers who laboured in poor conditions for low pay and had little to lose from striking. At the same time, the feeling that society was in a state of flux – which had been a nagging concern in pre-war German culture – was exacerbated by the conflict, and old political loyalties were eroded. Already deeply divided between reformist and revolutionary wings, the Social Democratic Party split in April 1917 over their continued support for the war effort, and 42 breakaway Reichstag deputies formed the Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Independent Social Democratic Party or USPD) which demanded an immediate end to the war and a radical programme of social and political reform. This schism was further widened by the Russian Revolution, which seemed to offer a model of radical action to those on the Left of the labour movement, especially with the trade unions and Majority Social Democrats (MSPD) cooperating with the state.4 At the same time, the Centre Party responded to the mood of their constituents and took up the popular cause of a negotiated peace, while the embattled bourgeoisie, fearful of defeat and revolution, retreated to the Right and adopted even more extreme positions in the face of widespread opposition and uncertainty.

These developments created a dangerous and highly combustible mood within Germany that threatened to explode at any moment. A year before the end of the war, there was a dramatic indication of the growing public hostility towards the imperial regime when between two and three thousand Berliners went on strike in protest over cuts in the bread ration and the regime’s vague promises of domestic reform after the war. The unrest quickly spread throughout the country and was largely orchestrated not by the official trade unions, but by radical elements within the labour movement such the Revolutionary Shop Stewards (Revolutionäre Obleute) in Berlin and unaffiliated radicals in other industrial cities. The demands of the strikers were both economic and political: lower food prices and higher wages, but also an end to the war, the restoration of civil liberties and domestic political reform. In this instance the trade unions and MSPD were able to reassert their authority and bring about a peaceful end to the strikes, but this was only a temporary truce in the struggle between government and workers.

Labour Unrest, 1913–19

Source: Geoff Layton, From Bismarck to Hitler: Germany 1890–1933 (London, 1995), p. 68

Industrial unrest flared up again in January 1918 when a week-long strike broke out following similar disturbances in Vienna and Budapest. Up to 1 million German workers downed tools, with around 500,000 striking in Berlin and many more coming out in sympathy in Cologne, Hamburg, Danzig, Leipzig, Nuremburg and Munich. The demands were similar to those made a year earlier, but there were now calls for solidarity with striking workers elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe which sounded dangerously like the kind of rhetoric used by the Russian Bolsheviks. Furthermore, this time the MSPD found itself unable to rein in the strikers, and, in a foreshadowing of events at the end of the year, they were forced to ride the tide of popular dissatisfaction and place themselves at the head of the movement for fear of losing the support of the working class once and for all. This being the case, the government hit back, imposing martial law, placing factories under military control, declaring a state of siege in Berlin and banning the Social Democratic newspaper Vorwärts. Nevertheless, a strike on this scale and for this duration was an ominous indication of the public mood, and contained clear signs that the social changes wrought by the war would have a significant impact on political events.

REVOLUTION FROM ABOVE AND BELOW

This was the situation when, on 29 September, the High Command informed the Kaiser that the war was for all intents and purposes lost. The failure of the German spring offensive, the Allied breakthrough on the Western Front on 8 August 1918 – Ludendorff’s ‘black day of the German Army’5 – and the collapse of Bulgarian and Austro–Hungarian forces on the Macedonian front in September, brought home to the High Command that its final gamble had failed and that an immediate surrender was essential to prevent invasion and social collapse. Believing that the Allies would deal more leniently with a civilian government, and wishing to pass the ignominy of surrender to someone else, Hindenburg and Ludendorff suddenly dropped their resistance to domestic reform and recommended that the Kaiser institute a programme of political reorganization. To this end, the moderate Prince Max von Baden was appointed chancellor on 3 October and for the first time two Social Democrats – the co-chairman of the SPD Philipp Scheidemann as minister without portfolio and the trade unionist Gustav Bauer as labour minister – were included in the cabinet. There followed three weeks of frantic attempts at reform which have been characterized as a ‘revolution from above’. The Prussian ‘three class’ voting franchise6, which had been introduced in 1849 and had long been a bête noire for the Left, was abolished; the personal prerogatives of the Kaiser (and in particular his powers to appoint ministers) were curtailed; and it was announced that henceforth the chancellor and the government would be accountable to the Reichstag. However, the practical effects of the reforms were limited by the fact that they were not widely publicized, and that the Reichstag almost immediately adjourned pending new elections. This was to have important consequences in the months that followed, as it meant that parliamentarians had little influence over subsequent events, leaving the fate of Germany in the hands of a small coterie of power brokers drawn from the ranks of the army, the old elites and labour movement.

At the same time, the revelation that Germany was surrendering unconditionally after four years of struggle and sacrifice destroyed the people’s confidence in the imperial government once and for all and unleashed a dramatic backlash against the existing regime. By the end of October Germany was a powder keg just waiting to explode. The spark that lit the fuse of revolution was the decision by right-wing officers amongst the High Seas Fleet (which had played little part in the war aside from the indecisive Battle of Jutland in 1916) to order the Kriegsmarine to put to sea for a final suicidal confrontation with the Royal Navy. When news of this impending Todeskampf (suicide offensive) leaked out it led to a mutiny at the naval base at the Baltic port of Kiel, and on Sunday 3 November more than 20,000 sailors and dockworkers gathered at a local park in a show of solidarity with the mutineers. The demonstration was met with force and seven people were killed and 29 injured when military police opened fire on the protestors. However, this only served to further radicalize the sailors, and the next day the whole of the Third Squadron of the fleet mutinied. Armed sailors then marched ashore and occupied the military prison, freed their comrades and then took over other strategic buildings. When soldiers from the local garrison were sent to put down the revolt they merely fraternized with the mutineers and went over to their side. By 6 November the disturbances had escalated, with dockworkers joining the rebels and the establishment of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils along the lines of those set up during the Russian Revolution of 1917.

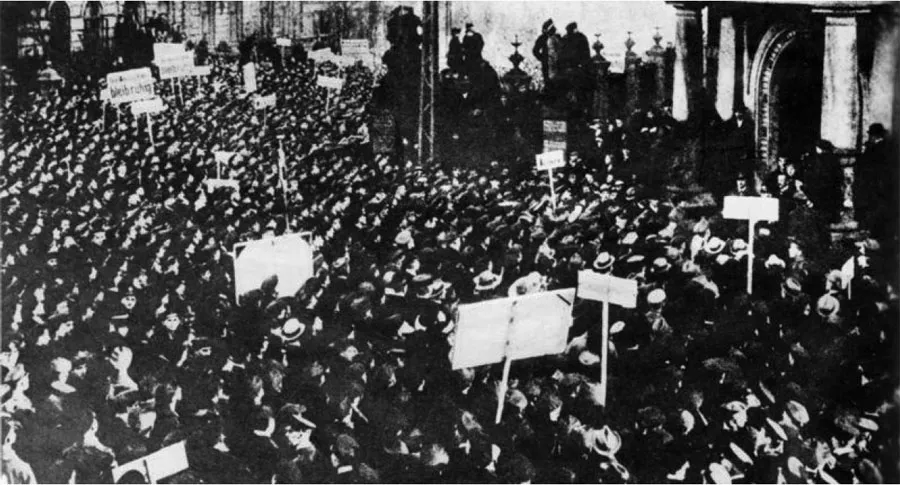

The beginning of the November Revolution: Anti-war demonstrations at Kiel, 4 November 1918 (Bundesarchiv Bild 183-R72520 / CC-BY-SA).

This was at first more of a spontaneous protest movement than a revolution. The Kiel mutineers were not trying to topple the government – if anything they saw themselves as defending it against reactionary elements within the officer corps. Nevertheless, once news of the disturbances at Kiel and the initial heavy-handed attempts to crush it leaked out, the discontent that had simmered beneath the surface for so long exploded into a full-blown revolution that quickly spread throughout the Reich. Across the country strikes were held, mass demonstrations staged and Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council established. This was followed by the occupation of public buildings and freeing of political prisoners, but there was little bloodshed: in most cases the authorities lost their nerve at the first sign of unrest and either fled or handed power to the councils. This was what happened in Bavaria, where anti-war demonstrations in Munich on 7 November led to the establishment of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils. That night the king fled Munich and the new ‘Revolutionary Parliament’ nominated the left-wing journalist Kurt Eisner as minister president. Within 24 hours, and without a shot being fired, the old regime in Bavaria had collapsed and power was in the hands of a scruffy-looking middle-class intellectual who claimed to represent the interests of the working classes.

So far the revolution had been a relatively bloodless affair, but there was deep concern that this could change at any moment. Hitherto the leadership of the SPD, with the help of the councils, had been able to maintain a reasonable amount of good order, but with radical forces within the labour movement – foremost among them the Spartakusbund (Spartacus League), a radical splinter group loosely affiliated with the USPD set up by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg in January 1916 – agitating for further change, the Social Democratic leader Friedrich Ebert and his comrades were uncertain as to how much longer popular dissatisfaction with the government could be held in check.

Matters came to a head on the morning of 9 November when the revolution reached the capital. By noon, news reached the Chancellor that large columns of workers were making their way to the city centre. Under pressure from the crowds outside, Prince Max felt that he had no choice but to act and issued a proclamation announcing the abdication of the Kaiser and crown prince and the formation of a regency. Meanwhile, a delegation of the SPD executive had arrived at the Chancellery to demand that they take over the government in order ‘to preserve law and order’. Prince Max was only too happy to comply and willingly handed power to Ebert, whose first act as chancellor was to call on the protestors to leave the streets.

However, this appeal, like the declaration of the Kaiser’s abdication, was too little too late. By one o’clock hundreds of thousands of workers had reached the city centre and, early in the afternoon, Karl Liebknecht and his supporters occupied the Imperial Palace, hauled down the imperial standard and replaced it with the red flag. Liebknecht then appeared before the dense crowds milling about between the palace and the Reichstag and delivered a fiery speech in which he proclaimed the formation of a Soviet republic. At roughly the same time, Phillip Scheidemann addressed the crowd in the hope of persuading them to disperse. Speaking from a window in the Reichstag, he announced the formation of a ‘labour government to which all socialist parties will belong’, exhorted the masses to ‘stand loyal and united’ and ended his oration with the words ‘Long live the German Republic!’7

Scheidemann believed that this was a decisive moment in the revolution, the point at which the crowds turned away from radicalism and the idea of a democratic republic became ‘a thing of life in the brains and heart of the masses’8. Yet this assessment smacks of wishful thinking. The republic still had a long way to go before it became a reality. That Ebert recognized the precarious nature of his position is evidenced by the precautions that he proceeded to take to ensure that, having gone this far, the revolution went no further. Even as the MSPD entered into feverish negotiations with the Independent Socialists in order to deliver the promised ‘labour government’, he never formally relinquished the title of Imperi...